Ukraine

Singing to Ukraine

February 23, 2022, was a relatively ordinary day on our planet. Until 10:30 p.m. Ontario time—early morning of February 24 where Nataliia Kurhan lives—when I heard a reporter announce breathlessly, “Missiles are being fired; the invasion has begun.”

I saw streaks descending behind the reporter on the screen and heard the sound of rockets.

Uncommon global access

The fact that Mennonites are spread throughout much of the world provides the global Anabaptist community with rare access to on-the-ground, first-person comment from both hotspots and forgotten corners of the globe.

Children taken from Ukrainian families

Parents in Molochansk, Ukraine, awoke one morning in May to a message from Russian authorities: “Dear parents: Evacuation has been announced at the school. Today, arrive at the school building with documents for the child and a minimum of things for a couple of weeks.”

Mennonites respond to recent military spending

From Dirk Willems loving his enemy in 1569 to Colombian Mennonites building peace today, Anabaptists have offered a bold peace witness. But being a peace church is complicated.

MCC supplies arrive for displaced Ukrainians

Before the fighting escalated in Ukraine this year, Nadiya O.* and her husband lived near the city of Uman, Ukraine. Together, they grew a vegetable garden and kept bees, selling their honey to make some extra cash. But shortly after the conflict worsened, her husband died from a heart attack.

Loss that cannot be counted

MCC partner Charitable Foundation Uman Help Center sets up a distribution event every week for food, hygiene supplies and other basic essentials for those living in or passing through Uman, Ukraine. (Photo courtesy of UMAN)

More than 100,000 people have fled to the area around the city of Uman in Ukraine as Russian military forces continue to advance. MCC partner Charitable Foundation UMAN Help Center distributes food; MCC hygiene kits, including toothpaste; and comforters to hundreds of people each month. (Photo courtesy of UMAN)

As millions of civilians continue to flee the devastation of the Russian military invasion of Ukraine, organizations like MCC partner UMAN (Charitable Foundation Uman Help Center) are working to support those who have left everything they know behind.

Is violence the best response to Putin?

‘Evening for Ukraine’ raises $220,000

A fundraising dinner to help people affected by the current war in Ukraine began with a man who had vivid memories of leaving Ukraine as a five-year-old in the mid-1940s. The man phoned Gerd Bartel, a well-known member of Peace Mennonite Church in Richmond, with the simple question, “What can we do to help people in Ukraine?”

Making comforters for Ukraine refugees a community effort

Niagara United Mennonite Church called its congregants and neighbourhood community together to tie comforters in the church basement on March 26. Advertisements in the local newspapers and in church bulletins invited anyone interested to gather for the morning.

Mend our beating heart

My grandfather, Harry Giesbrecht, referred to the country, language and people of Ukraine as his “beating heart.” The many trips back “home” breathed life into his aging lungs. The cool water of the Dnieper, the pothole-riddled roads near Lichtenau, Molochansk and Nikopol, and the patriotic anthems transformed my 80-year-old grandfather into a young man.

MCC partners in Ukraine work to meet physical and spiritual needs

In the silence that lived between the deadly warnings of air raid sirens, the sound of a small choir, singing a song of praise, echoed out of a church sanctuary in western Ukraine. Just the night before, Anna, administrative coordinator for Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Ukraine, had absent-mindedly hummed a few bars of the song during an evening tea break at the church.

Mennonite organizations providing aid in Ukraine

A humanitarian aid organization in Molochansk, Ukraine, founded by Canadian Mennonites continues to help the community amidst Russia’s ongoing invasion.

Mennonites in angst over Ukraine invasion

It’s 10:30 a.m. in Winnipeg, but for Valerie Alipova, it might as well be after supper.

Watch: MCC partner in Ukraine asks for prayer

A Mennonite Central Committee partner in Ukraine requests prayer in a video clip the relief organization posted on YouTube earlier today.

Two years in

Since March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic came into the lives of Canadians, this magazine has published many accounts of life in pandemic times. There have been reports on how Mennonite churches and organizations have adapted to health restrictions, found new ways to care for others, and even managed to have fun, despite the challenges.

Prayer for the war in Ukraine

(Photo by Elena Mozhvilo/Unsplash)

God of hope,

we pray to you when hope is scarce

as our world convulses with the horror of war.

You alone know the extent of the crimes committed in Ukraine:

the people murdered, the homes and infrastructure destroyed,

the way violence comes as a calamity,

cutting a swath through the world.

Why is power concentrated in the hands of so few?

How can we make this war stop?

You alone know a way out of this quagmire of evil.

Help us find it.

Awaken those who dismiss this as someone else’s problem.

MCC pulls staff from Ukraine

Russia has begun military operations against Ukraine, but North American Mennonite Central Committee staff who were working in the latter country are safe.

That includes Winnipegger Andrea Shalay, the charity’s peace engagement co-ordinator for Europe. Shalay and three other staff, all Americans, were evacuated from Ukraine more than a week ago.

‘Bring us beyond our own stories’

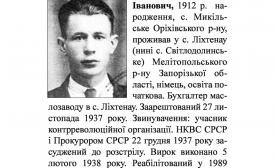

Among the voluminous lists of those disappeared during the dark times in what is now Ukraine, researchers have found roughly 400 pages of Mennonite names, with five or six names per page. That is just for Zaporizhzhia province. The lists for all Ukrainian provinces are available online, though printed in Cyrillic script.

An eye-witness account of Nazi occupation

At the age of 85, I am probably one of the few survivors of the German occupation of Ukraine/Russia from 1941 to 1943 who still have clear personal memories of that time.

UWinnipeg Fellowship to crack open KGB archives

In the 1930s, thousands of Mennonites disappeared in the Soviet Union without a trace. The KGB archives in Ukraine has thousands of files on these missing Mennonites, and a newly announced University of Winnipeg Fellowship wants to crack into these archives to uncover the stories of lost relatives, ancestors and much more.

Mennonite diaspora encounters Muslims in the Russian Empire

Seth Ratzlaff, left, a student at Conrad Grebel University College, his father Victor, lay minister of Westview Christian Fellowship in St. Catharines, Ont., and Aileen Friesen, the J. Winfield Fretz Visiting Research Scholar in Mennonite Studies, discuss her ‘Muslim-Mennonite Encounters in the Russian Empire’ lecture on Jan. 25, 2018. (Photo by Dave Rogalsky)

Aileen Friesen was the go-to person to help visitors order in Russian cafés at a scholarly gathering in Russia’s Far East, according to Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College’s dean. Epp introduced Friesen as the inaugural J. Winfield Fretz Visiting Research Scholar in Mennonite Studies before Friesen’s lecture on ‘Muslim-Mennonite Encounters in the Russian Empire’ on Jan.