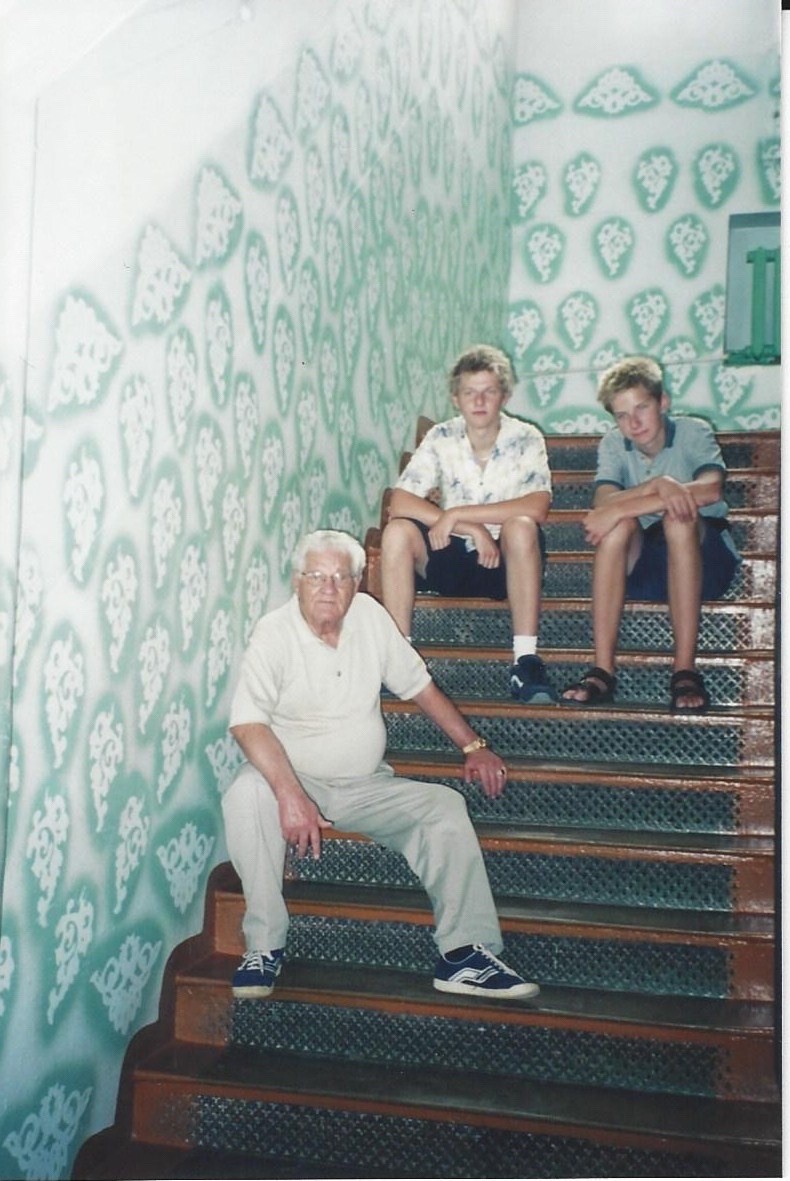

My grandfather, Harry Giesbrecht, referred to the country, language and people of Ukraine as his “beating heart.” The many trips back “home” breathed life into his aging lungs. The cool water of the Dnieper, the pothole-riddled roads near Lichtenau, Molochansk and Nikopol, and the patriotic anthems transformed my 80-year-old grandfather into a young man. During the many times I accompanied him, this transformation occurred right before my eyes.

Opa grew up shoeless on the banks of the Dnieper River during Stalin’s infamous purges. His family was fractured because of Stalin and the Second World War. His brother died, his father was sent to Siberia and his friend was killed. At 16 he was forced to fight in the war. He survived and on May 1, 1948, Opa arrived in Canada. It is a day we still celebrate, seven years after his passing.

I grew up with his stories and they created a close bond between us. His story of escape and survival captivated me. Much of our time together centered on these stories and our conversations were a mixture of wonderful memories of his childhood, which was filled with boyish joy.

But woven into that joy was the absolute terror of war—the terror that still woke my grandfather in the middle of the night as an old man. My studies and my passions became intertwined with this history and our conversations.

I spent 10 years of my life traveling, writing and tracing Opa’s steps through Ukraine. There is something powerful about touching the ground your ancestors worked and lived on. It shapes you. What Opa’s generation went through and faced no one should ever have to.

I used to think his story was unique. I thought it was powerful how he survived and was able to prosper. It is an important part of his story. As I got older and matured, I realized the true power of his story is that it was one individual example of what countless Mennonites endured. My grandfather’s story, as harsh as it was, was just one grain of salt in the hourglass.

This realization unites Mennonites across Canada. Every family that made the trek from Ukraine and the former USSR from 1918 to 1948 is united. The stories, conversations and history stick to us like the thick clay of the Assiniboine River during a Manitoba spring. Every Mennonite family that I know has a story about relatives who dodged gunfire and explosions, fleeing with what they could carry on their backs. But even after all the pain and suffering, there still were whispers of joy—memories of a better time.

Despite all the suffering these families went through we have this deep-seated connection to the golden grain fields of Ukraine. It is one of the main reasons so many fleeing Mennonites chose Manitoba as their new home: it looked like their last one.

This is why the war in Ukraine is visceral for so many Mennonites today. It feels like we are losing our homeland all over again. We watch the death and destruction on the news. We see the faces of our parents and grandparents in the victims of this heinous invasion. Generational wounds are being sliced open.

Mennonites are also known for helping their neighbours. The first chance Opa got later in life, he went back “home” and started giving back to the people of his former community. For 15 years, Opa was a board member of the Friends of the Mennonite Centre in Ukraine. He wanted to give back to the people who lost so much. His history, his home and his past shaped him. And he didn’t want future children to lose their childhood like he did.

Today, our neighbours need us more than ever. Many are hiding in shelters, holding onto hope that this war will end soon. Millions of others have fled the country. They have begun the same trek our parents and grandparents made 80-plus years ago. They are travelling the same dirt roads looking for safety, with nothing more than what they can carry on their backs. They are bleeding, each of them leaving their “beating heart” behind in a pile of rubble.

We need to help this next generation of refugees on their journey and tend to their wounds, provide shelter for those with none and feed those who are hungry. We need to help mend their beating hearts. Perhaps our care will mend our own wounds of the past as well.

Michael Wilms lives in Winnipeg. He is a board member of the Friends of the Mennonite Centre in Ukraine, which his grandfather co-founded. Michael spent a decade retracing his grandfather’s footsteps and backpacking through Europe, which culminated in his 2015 book, The Grain Fields. Read more of Michael’s writing at thegrainfields.com.

—Corrected March 31, 2022. The photo captions initially misidentited the Chortitza Mädchenschule as the Mennonite Centre in Molochansk. The captions have been updated.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.