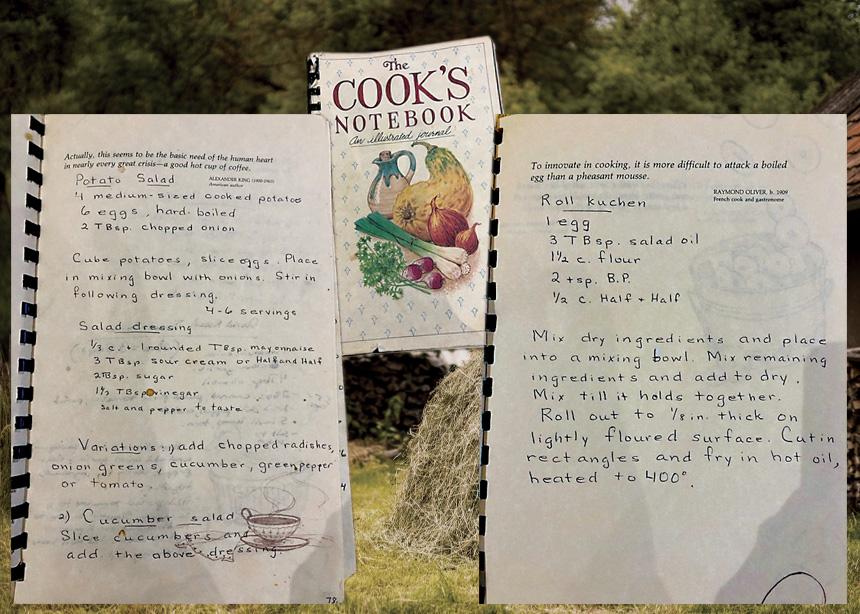

In 1989, my grandmother, Lorraine Braun, began creating a cookbook for my mother, Maurya. For three decades, she handwrote recipes of foods that were significant in our family or the Mennonite community. This recipe book is a central memory from my childhood.

The book’s pages are covered with the ketchup we used to make rib sauce or smattered with oil from sitting open next to the rollkuchen deep fryer.

The book tells the story of our family, but it also tells a larger historical story. Through a collection of recipes that can be traced from the Netherlands to Russia, following a pattern of flight and persecution, it provides an account of the displacement of Mennonites.

Handwritten recipe books and the practice of recipe sharing were, and continue to be, a way for Mennonite families to find a sense of identity that was not rooted in a geographical location. These recipes taught young community members like me about the importance of remembrance and tradition. They also helped us to learn that Mennonites value memory because of their complex history of displacement, persecution and the search for a safe home.

When I ask my mother about trauma and displacement, she recalls a story that signifies the depth of the brutality our family experienced because of our pacifism. Her grandfather, a Mennonite colonist and eventual immigrant to Canada, was called to fight for the Russian White Army. Unwilling to compromise his pacifist beliefs, he deserted and fled back to his farm. Officials searched his land for days while he hid in a haystack, his family bringing him food and news when they could. At one point, officers stabbed the haystack with pitchforks, looking for him. His survival and subsequent escape to Canada were nothing short of miraculous. But his experience traumatized him. His story was shared by aunts and uncles, but he would never speak about it directly.

Still, it looms large in my own understanding of Mennonite history. I can imagine the terror. I can also imagine how ostracized my family and others like them must have felt. They moved from one place to another, and in every country, they were labelled undesirable. When my mother’s family fled to Canada, they brought with them only what they could carry. A significant portion of this was memory—memory of the places they had been and the homes they had tried to create.

The cabbage rolls and watermelon salad I remember eating as a child became part of our family’s cuisine because their forebears harvested the fresh ingredients for them from their Russian farmland. Even simple dishes like potato salad with a vinegar base carry German influence— the home they were forced to leave before coming to Russia. The result is my mother’s cookbook.

Conversations about migration and expulsion, my mother recollects, often occurred in the kitchen. These conversations, and the act of cooking food while speaking about her ancestors, is what gave her a sense of the fluidity of Mennonite identity. She says that while “[Mennonites] didn’t have a homeland anymore…[they] still knew who [they] were,” in large part because they were able to carry their experiences through the ways they cooked.

Passing on recipes provided an opportunity to tell stories that often stirred up traumatic memories. While making rollkuchen, she might have discussed her family’s migration from Germany. Eating watermelon salad on a hot summer day brought up questions about farming in Russia. The first time I heard the story about my great-grandfather hiding in the haystack to escape the White Army was around a kitchen table. I remember my grandmother telling me similar stories when I was old enough to help prepare traditional foods. The kitchen became a safe space to discuss traumatic and complex issues in the formation of our family’s identity.

For my mother, there is no one way to be Mennonite, but she has also never felt confused about what it means to be a Mennonite—a fact that she attributes to the rich tradition of recipe sharing in her home.

My mother’s cookbook serves as a physical artifact that mirrors the experiences of refuge-seeking and homecoming that loomed large in the collective memory of her family.

Fionnuala Braun is a research officer in the College of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.