Since her death in 1943, Simone Weil’s philosophy has impacted dozens of writers, thinkers and theologians. T.S. Eliot named her a saint. Simone de Beauvoir envied her spirit.

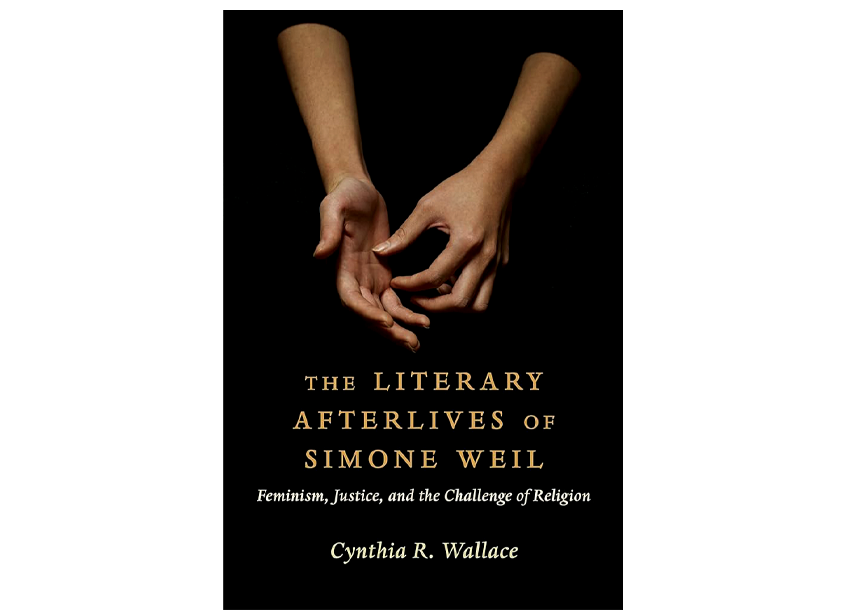

Now, in The Literary Afterlives of Simone Weil: Feminism, Justice, and the Challenge of Religion, Cindy Wallace examines how nine writers, including Adrienne Rich, Annie Dillard and the Mennonite poet Sarah Klassen, interact with the French philosopher and activist in their work. The book was released by Columbia University Press earlier this year.

Simone Weil’s short life was admirable. She was a teacher of the Classics who sought solidarity with those who suffered by working in a factory. She later joined the anti-fascist resistance in the Spanish Civil War.

Raised as an agnostic by Jewish parents, Weil had mystical encounters with Christ in her late 20s. This informed her writing about Christ and the spiritual life. She died in England at 34, after contracting tuberculosis and refusing to eat more than those who were resisting Hitler’s regime in France.

Wallace, who teaches English at St. Thomas More College at the University of Saskatchewan and writes a column for Canadian Mennonite, shared what inspires her in Weil’s work and why Weil can resonate with church communities as well as writers. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Which important ideas of Weil’s do you focus on?

The first is her interest in attention as a contemplative discipline of openness. Weil argues that we pay attention to our homework, to works of art and poetry, but we also pay attention in spiritual practice like prayer and in the ethical practice of focusing on someone who is really suffering.

The second is her moral seriousness. She’s very concerned with justice. In Weil’s thought, her religious interest and her politics are integrated. Her fascination with Christ wasn’t separate from her critique of colonization and she was one of the first Europeans to criticize European colonization openly.

The third thing is Weil’s grappling with religion. She had mystical experiences yet she was so critical of the church as an institution. Weil is a good model of what it can look like to have a faith that’s open to mystery and also refuses to be comfortable with what the church has gotten wrong.

As a Mennonite, what inspires you about Weil’s work?

I’m attracted to the way that Weil refuses modes of “power over.” It resonates with Mennonite theology that takes seriously Jesus’ humility. I also think her integrity aligns with our interest in radical discipleship, where we think that Jesus meant what he said when he called people into action. That was the way she sought to live her life and the way she wrote her philosophy.

Also, as a Mennonite situated on Treaty 6 and Metis homeland, I have to appreciate Weil’s critique of colonization, which I learn from because it cost her. She kept talking about it when nobody else was.

Your book examines literary art— poems, a novel, creative non-fiction—that is inspired by Weil’s life and writing. What role can art play within the spiritual journey or a church community? Does Weil speak to this?

Weil argues that one of the ways we can love God is by appreciating beauty because all beauty comes from God. A lot of Mennonites I know have a deep appreciation for the land, seasons, nature, flower gardens, which is legitimate, but there’s also this possibility in poetry, visual arts and in literature, which can sometimes feel intimidating and elitist.

Weil believed that all of the greatest beauty in the world ought to be accessible to all people and so she taught the Classics to wage workers in factories. She believed having a heart and life that was open to the beauty humans could make was dignifying and enlivening for every person. I think that’s something we could think about as communities.

As Mennonites, we value simplicity and I love it and I’m convicted by it, but beauty has a potential to wake us up to truth and goodness, which I believe, with Weil, comes from God.

What did you learn from this project?

Over and over again, in moments where there’s no room to talk about religion in public life or what it looks like to choose self-sacrifice over comfort, to choose to take up our crosses and follow Jesus in a literal way—different generations of writers find a conversation partner in Weil.

She doesn’t give all the answers, but she is provocative and countercultural enough to makes us think, ‘Oh maybe business as usual isn’t the best way to live a full and fruitful life.’ She’s a conversation partner for questions about what it looks like to live a countercultural life that’s still open to beauty, goodness and joy.

It’s easy to assume the countercultural struggle is a bit of a slog.

What I love about Weil is that she’s really insistent that we see the world for how it really is. She never lets us pretend away injustice. But she’s just as insistent that we see what’s beautiful and that we see the goodness of friendship and community.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.