An early morning fire and smudging ceremony started each day of Native Assembly 2014 that met from July 28 to 31 at the edge of the Assiniboine Forest on the Canadian Mennonite University campus. A tepee and several tents served as their backdrop, and although the sound of traffic never let up, participants could watch a raccoon or a fawn nursing from its mother or hear the birdsong amid the bustle.

“We gather as spiritual people with our ears to the earth and eyes to God,” was the call to worship every morning following the assembly fire and prayer time.

Every morning and evening worship time focused on the theme, “Ears to earth, eyes to God,” and featured a speaker who told stories, offered teachings and challenged listeners.

This year’s agenda primarily focused on building relationships with God, with each other and with God’s creation. This simple agenda was reiterated in many ways and set the tone for a moving and powerful exchange between first nations and the “Mennonite nation,” as speaker Thelma Meade chose to call the non-native participants.

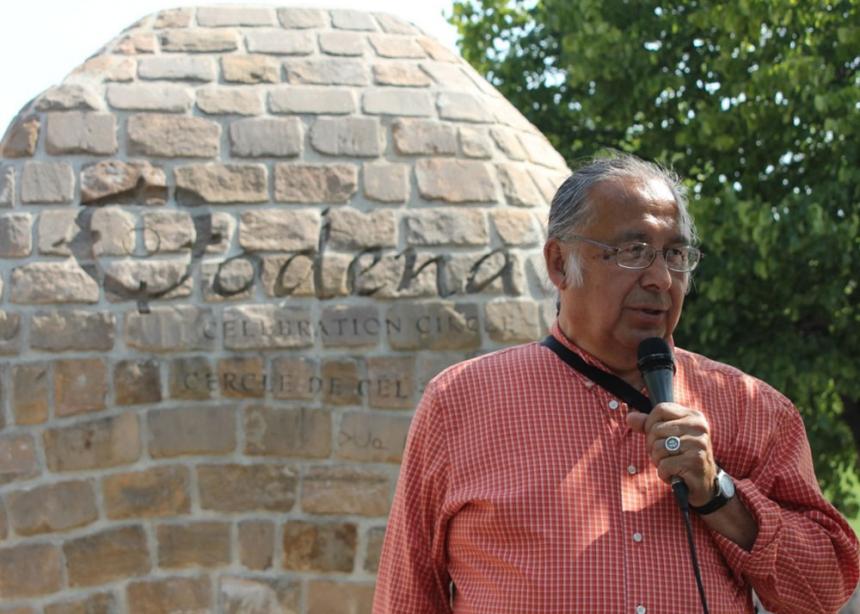

Stan McKay, former moderator of the United Church of Canada and director of the Dr. Jessie Salteaux Spiritual Centre, said, “We are in desperate times. Many signs indicate we are not caring for each other and for the earth, but we still have strawberries,” an important traditional medicinal/healing plant.

“We don’t own the earth, but we are called to protect it,” he said. In talking about right relationships, he said, “Laugh at ourselves and each other. It’s about humility and respect. I invite you to risk laughter.”

Niigaan (James) Sinclair said, “When you receive a gift, you carry the responsibility of it.” In the past, he said the relationship Christians had with indigenous people was one of hierarchy and abuse, and the residential schools created a legacy of mistrust. “Now it is hard to accept that the church has any gifts to give us. Gifts can, however, teach us patience and responsibility, but we need to spend every day—our entire life—at it, so that maybe we can rectify the relationship.”

That work was clearly the focus of Native Assembly 2014, as approximately 250 indigenous and (mostly) settler people from across North America gathered to learn from each other and listen to each other’s stories.

In his workshop, Vincent Solomon, an Anglican priest and Aboriginal Neighbours coordinator for Mennonite Central Committee Manitoba, offered many illustrations of points of agreement between Christian teachings and indigenous belief. “If early missionaries would have presented Jesus Christ in a way that allowed the aboriginal teachings to be infused with the gospel, you would have found that aboriginal people today would not be in the state that many of us are,” he said.

Solomon sees a growing interest in indigenous spirituality, “in wanting to understand it through a Christian perspective. For me, that is a very encouraging thing,” he said. “One of the things that the Mennonite church has to offer is their ability and desire to serve. Their faith perspective throughout history is a gift that can be used for first nations people, acknowledging that there were a lot of mistakes made. Reconciliation involves more than just saying ‘sorry,’ though. It involves action, whatever that might look like individually or corporately, and it involves an ongoing dialogue. It is time to dialogue on how we can live together, not the way we used to. I am very grateful for events like this.”

Adrian Jacobs, keeper of the circle at Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre in Beausejour, Man., a ministry training school that combines Christian and traditional indigenous teachings, said, “If the love of God does not translate into love of people, I’m not sure what you’ve got.”

In his gentle way, Jacobs called listeners to reconnect with the land. “The Creator is talking,” he said. “Are we listening, listening to what creation is saying and ready to change in response to this? Mennonites have a farming background, but many have forgotten it in their modern way, but the earth is still calling, talking to us.”

Steve Heinrichs, director of indigenous relations for Mennonite Church Canada, and part of the MC Canada and the Partnership Circle of MC Manitoba planning committee, said, “The gospel calls us into the marginal places as privileged people, and so in this critical time we need to hear from diverse voices.”

“Let’s share our gifts,” he said, “as long as we are also willing to share gifts from the indigenous. We have entered into a relationship, engaged in dialogue and profound theological sharing. I think we need to move beyond our existing relationships with indigenous people.”

Jacobs echoed that sentiment: “I would hope that at the next assembly [in Alabama in 2016], Mennonites and native people will be able to share stories of a relationship that has developed. Engage the first nation people who are your neighbours and begin a relationship with them. A good sign for the next assembly would be if all the Mennonite churches would know on what treaty territory their local community is and what is the story of that community.”

More on Native Assembly 2014:

Personal reflection: Searching for harmony

Personal reflection: In another skin

Young Voices personal reflection: A world of diverse Mennonite faith

The land at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in downtown Winnipeg was too important as an inter-tribal meeting and trading place to be held by any one people, says Clarence Nepinak, a learning tour leader at Native Assembly 2014. (Photo by Moses Falco)

Steve Heinrichs, director of indigenous relations for Mennonite Church Canada, leads in singing during one of Native Assembly 2014’s worship services. (Photo by Evelyn Rempel Petkau)

In the Blanket Exercise, quilts covering the floor are Turtle Island—aka North America. The blankets are folded and removed to represent the insidious ways that land and control were taken from Indigenous Peoples through colonialism. Participants are crowded into smaller and smaller areas, or sent back to their seats to represent those who died from disease or imposed malnutrition. (Photo by Moses Falco)

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.