A major sociological study of American youth concluded that their understanding of faith could be called “moralistic therapeutic deism.” On page 16 of the magazine, Ryan Dueck makes a related observation about “therapeutic church” and says it’s a problem.

From their study of youth, Christian Smith and Melinda Lindquist identified a constellation of common beliefs: God exists; God is politely involved in a believer’s life when there’s a problem; God wants people to be nice; the main goal of life is to be happy. These views are probably prevalent in most Canadian churches today.

In other words, contemporary Christianity is a genteel (and gentle) morality. Smith and Denton write: “[God is] something like a combination Divine Butler and Cosmic Therapist: he’s always on call, takes care of any problems that arise, professionally helps his people to feel better about themselves, and does not become too personally involved in the process.”

Dueck’s discussion of therapeutic church looks specifically at the progressive Christian circles he finds himself in. In his view, the church should not be a social justice club with a little bit of Jesus sprinkled on top (my words), or “the NDP at prayer,” as another denomination is sometimes called.

I circulate in similar circles and have similar concerns. On one overseas delegation with a Christian human rights agency, I was astonished at how much I craved collective prayer. My commitment to human rights, ecological justice and the like are rooted in Christian commitments and practices, including an ineffable sense of a mystical encountering of Jesus in the people living in difficult conditions.

As I asked in my October column, what is the role of faith in a theory of social change? What about the action of the divine mystery in personal change (conversion)?

Neither a nice, pleasant spirituality (God-as-therapist) or secularized justice-as-faith (God as activist-in-chief) are the robust, multi-faceted deity represented in the Bible and Christian history. More importantly, do these narrowed versions compel people to a discipleship that embodies the call to imitate Jesus?

I have been affiliated with more than one Christian social justice organization that became a social justice organization only. I worry about the consequences of this for the body of Christ.

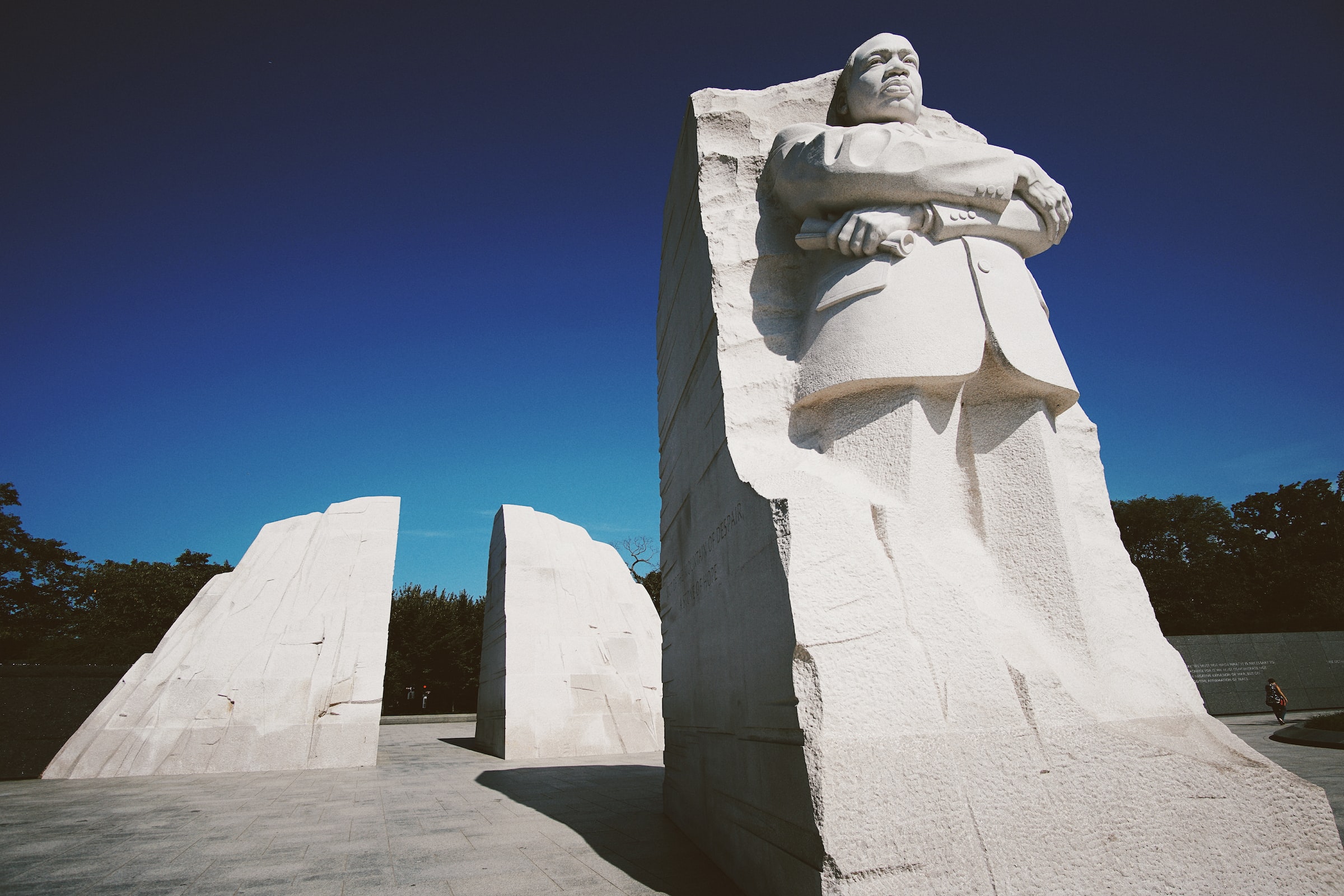

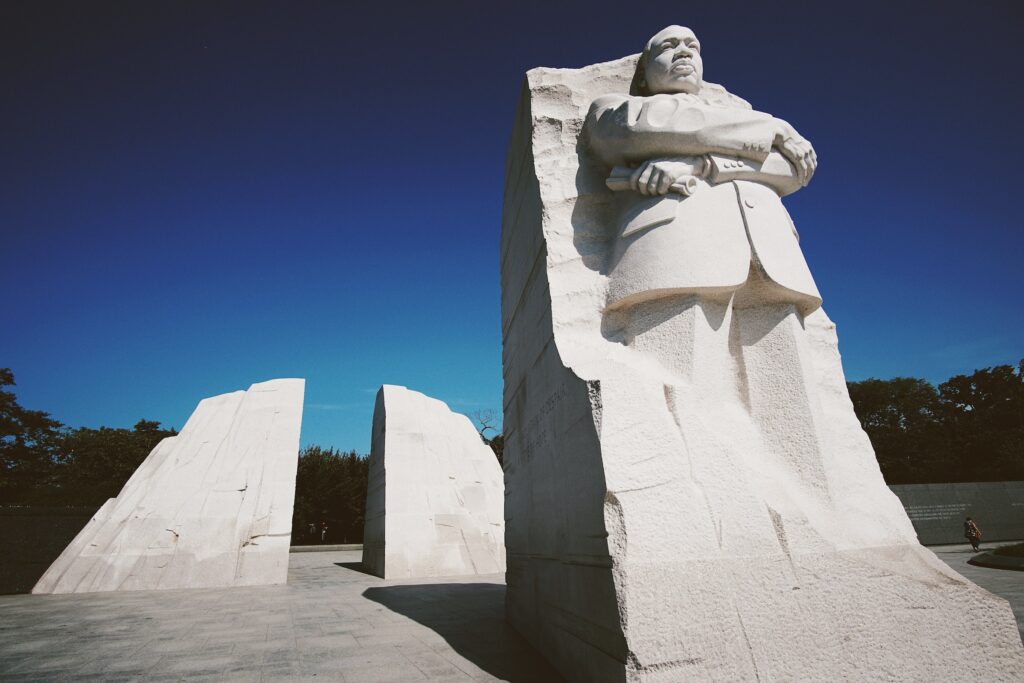

Last month, the U.S. celebrated Martin Luther King Jr Day. Note that about three-quarters of Americans “disapproved of Martin when he was shot,” Cornell West said in the Boston Review.

King’s words on racism and civil rights were not nice, feel-good words. His speeches on war and capitalism were even more disturbing. King’s vision of God was not remote, anemic or therapeutic. For King, only a deeply engaged and actively practiced faith could lead others to overcome police dogs and social derision:

“When our days become dreary with low-hovering clouds of despair, and when our nights become darker than a thousand midnights, let us remember that there is a creative force in this universe, working to pull down the gigantic mountains of evil, a power that is able to make a way out of no way and transform dark yesterdays into bright tomorrows.”

This is neither therapeutic faith nor secular progressivism. It is a God who sets hearts aflame. May we so preach such a God, our Lord and Brother Jesus.

Randolph Haluza-DeLay considers MLK one of his heroes of faith.

Read more Mind and Soul columns:

Christmas delight?

Writing for the foyer

What is your theory of social change?

Climate imagination

Cycling the Black history of Ontario

LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0geyBtYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAzMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbiB7IGJvdHRvbTogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcik7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDAgMCA1cHggMDsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IHVse2xpc3Qtc3R5bGU6bm9uZTttYXJnaW46MCAwIDEuNWVtIDA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse21hcmdpbjowICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3RvcDowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHtncmlkLXJvdy1lbmQ6dW5zZXQgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6OmJlZm9yZXtjb250ZW50OiIiO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3BhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxsOjptYXJrZXJ7Y29udGVudDoiIn0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgaW1ne2hlaWdodDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7d2lkdGg6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7YWxpZ24tc2VsZjplbmR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczpyZXBlYXQoMTIsIDFmcil9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1jb2xsYWdlIGltZ3toZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MDtncmlkLWF1dG8tcm93czoxcHg7b3BhY2l0eTowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgaW1nLC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpZnJhbWUsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHZpZGVvey1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt3aWR0aDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7ZGlzcGxheTpibG9ja30udGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbntwb3NpdGlvbjphYnNvbHV0ZTtib3R0b206MDt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjYpO3BhZGRpbmc6NXB4IDJweDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtjb2xvcjojMzMzfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uOmVtcHR5e2JhY2tncm91bmQ6dHJhbnNwYXJlbnQgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgZmlndXJle2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IGltZ3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDoxMDAlOy1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjpib3R0b219I2xlZnQtYXJlYSB1bC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5e2xpc3Qtc3R5bGUtdHlwZTpub25lO3BhZGRpbmc6MH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uIHsgYm90dG9tOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHsgcGFkZGluZzogMCAwIDVweCAwOyB9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb24geyBib3R0b206IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgeyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgeyBwYWRkaW5nOiAwIDAgNXB4IDA7IH0gIH0g

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.