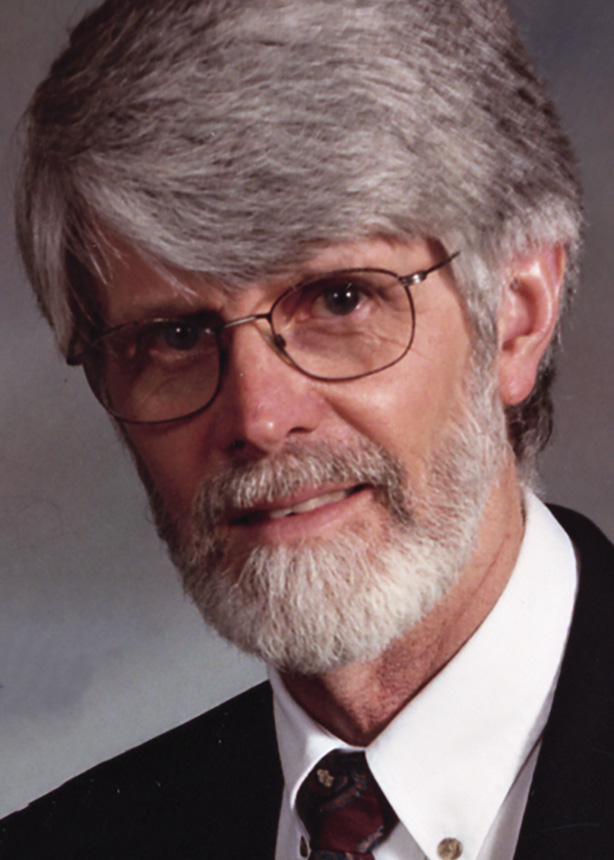

In the summer of 2003, as I pondered how to say farewell to a 24-year career as editor of Canadian Mennonite and its predecessor, Mennonite Reporter, a friend suggested I reflect back on some defining moments.

In the summer of 2003, as I pondered how to say farewell to a 24-year career as editor of Canadian Mennonite and its predecessor, Mennonite Reporter, a friend suggested I reflect back on some defining moments.

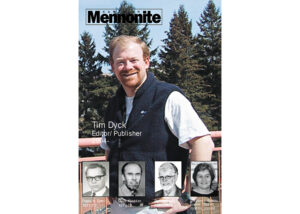

I could think of many such moments, but the one that loomed the largest was what happened in 1997. The last issue of the tabloid newspaper Mennonite Reporter was dated Sept. 1, 1997. It was succeeded on Sept. 15 by Canadian Mennonite, the magazine that is now marking its 25th anniversary.

How and why did that happen? What was significant about this transition 25 years ago? What can be learned from that history, given all the changes in the publishing world since then?

“At the risk of sounding melodramatic,” I wrote in a 1992 memo to the board of Mennonite Publishing Service (MPS), the publisher of Mennonite Reporter, “we’re facing a watershed moment.” A Conference of Mennonites in Canada (CMC) task force on communication had just proposed that the conference establish its own publication, rather than continue to promote and subsidize subscriptions to Mennonite Reporter.

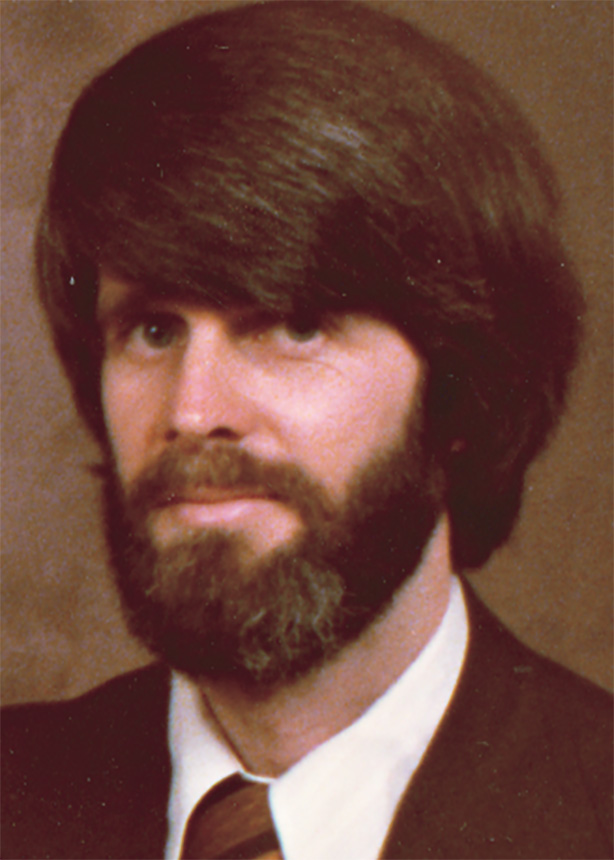

I couldn’t help but take this news somewhat personally. Since becoming editor in 1979, I—along with the staff and board team—had worked hard to provide a newspaper for Mennonites in all parts of the country. We transitioned from an Ontario-based board to one with representation from across the country. We appointed regional correspondents to gather stories and explore issues of the day. Through commentary and letters, we provided a forum for exchanges of opinion on key issues.

We offered special insert pages for conferences and church organizations that wanted to frame their own stories in addition to having their news and stories told by a reporter. We took steps to bolster circulation across the country. The paper had strong Ontario circulation, with an every-home plan funded by several Ontario Mennonite conferences. But circulation numbers in the four western provinces weren’t as strong.

Progress on a broader Canada-wide uptake of Mennonite Reporter seemed stalled. CMC’s resolve to start its own publication—which it did with the publication of a newsletter called Nexus from 1994 to 1997—served as a jolt in the conversations about the future of Mennonite Reporter. It was becoming clear that we needed to look not only at better marketing, but at the publication itself, at its content and editorial policies.

During this same period, the conversation between MPS and CMC intensified. In 1995, a publication steering committee—with representatives from both entities—was formed to test “the feasibility of making Mennonite Reporter the primary printed communications vehicle within the Conference of Mennonites in Canada, for distribution to every household.”

The process was intense. Numerous meetings culminated in an October 1995 consultation in Winnipeg involving around 40 people. Information from more than 20 focus groups from across Canada helped to inform the discussion and decisions.

At the consultation, Mennonite Reporter brought ideas, such as expanding its longstanding attention to news with a wider variety of articles, such as profiles of people living out their faith; inspirational and instructional articles offering practical spiritual help; and birth, marriage, baptism and death notices. Also discussed was a change of format from a newspaper to a magazine, which some folks said is easier to handle, especially on the bus or in the bathroom.

The consultation agreed to “recreate” Mennonite Reporter into a periodical for all conference households. There was broad support for the proposed expanded content and a switch from newspaper to a magazine format.

An early prototype was circulated in April 1996. For three months in the fall of 1996, I devoted a third of my time on planning for the anticipated new publication. During this time, I and Jack Suderman, at that time executive secretary of the CMC Resources Commission, held face-to-face discussions in each of the five area conferences, from Ontario west to B.C.

Less easily resolved, however, were questions about ownership, accountability, editorial policy and finances. Would a new publication have to be owned and operated as a department of the conference for it to be accepted? Could there continue to be a partnership between the conference and MPS as a separately incorporated publishing entity, with a cost-sharing arrangement, and room for the practice of editorial freedom? If not, should the new publication go completely independent?

In follow-up meetings of the publication steering committee, I presented a draft statement of editorial mandate and philosophy: “While guided by the church’s confession of faith and its policies, the magazine maintains that the welfare and vitality of the church are best served through a policy of editorial openness and balance. This means that the magazine has the responsibility and the freedom to seek out information and insight in the service of the reader and the common good, and to permit voices from across the conference continuum and the larger Mennonite community to be heard.”

At one meeting, a few of us worked late into the night to consider how the editorial mandate could elicit broader acceptance and trust, and also help the proposed new publication embody its best intentions. Suderman proposed a theological formulation based on an understanding of the church as a “covenanted community of believers.”

Informed by this perspective, the committee embraced the following framework for an editorial mandate: “A covenant is an agreement that establishes a relationship and implies a commitment to: dialogue with each other; know and understand each other better; discern God’s will together; encourage the full use of our gifts to edify and build up the church; search for truth together; mutual encouragement and exhortation. This new periodical will function as a communications instrument which promotes covenantal relationships.”

The statement seemed to resonate in enough places that a path forward opened up. A full prototype of Canadian Mennonite was widely distributed in early 1997. In the 1997 spring and summer sessions of all conferences, the proposal “for a Canadian Mennonite periodical to help build an informed and faithful church” was approved.

And the first issue of Canadian Mennonite was published Sept. 15, 1997.

In 2003, as I prepared to leave the editorial post at Canadian Mennonite, I editorialized on the 1997 defining moment: “We gave up an old familiar name and took on a new identity. We gave up the familiar tabloid format and took on the form of a magazine. . . . We expanded the content . . . .

“The conferences in turn also had to give and take. They got more representation on the board. But they also agreed to some limitations on that control. They agreed to leave the paper as a separately incorporated entity. They agreed to an editorial policy which says that the practice of editorial freedom can be a good thing when exercised in the service of the truth which the church itself espouses. They agreed to discontinue their own publication and support the newly emerging Canadian Mennonite with a cost-sharing formula.”

I concluded: “As all the issues were clearly identified and laid out on the table, the bonds of trust were being strengthened.”

Trust. Covenant. These were some of the key understandings that helped launch a revitalized publishing partnership 25 years ago. These core values and commitments proved to be foundational, as they were revisited and renegotiated often in the ensuing years.

In 1997, print still ruled and online publication was just beginning. The Canadian Mennonite website was not interactive. Social media were not widely in use. Church attendance and institutional loyalty were still relatively high. Changes in these areas would mark the communication opportunities and challenges of the subsequent years. Those chapters are best written by others.

For discussion

1. What are some of the biggest changes you have experienced in your lifetime? Have you ever ended something that was sputtering and then courageously tried to create something new to replace it? Under what conditions is it important to take that kind of risk?

2. Mennonite Reporter had been primarily a news organization, but the proposal for Canadian Mennonite was to include a wider variety of inspirational articles. How well has CM managed to balance news and inspiration? What kinds of articles do you find most encouraging? Do you have suggestions for improving the content?

3. Ron Rempel writes that the church conferences “agreed to leave the paper as a separately incorporated entity.” Can you think of times when church bodies were frustrated by CM’s editorial freedom? Does an independent press work differently in church circles than it does in secular politics? How important is it to have an independent press?

4. What role does CM play in providing communications between Mennonites across Canada? Where else do you get information about what is happening in the Mennonite churches? Has the pandemic changed how your congregation distributes information?

5. As paper and postage get more expensive, should CM put more energy into online content? How do you think church communications might change in the future?

—By Barb Draper

Read more stories from CM’s 25th anniversary issue:

Editorial: Giving thanks for 25 years

Tim Miller Dyck: ‘We declare to you . . .’

Donita Wiebe-Neufeld: Still happening

Angelika Dawson: Two stories about my son

Dave Rogalsky: Visiting congregations

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.