In the midst of the #MeToo movement, in which those in positions of power are being called to account for sexual abuse, a conference hosted by four Manitoba Mennonite organizations acknowledged that it happens in the church, too.

From May 31 to June 1, about 100 church leaders and lay people gathered at Canadian Mennonite University (CMU) in Winnipeg to hear theological insights, practical guidelines and personal stories around sexual abuse and ministerial misconduct.

The conference—co-sponsored by CMU, Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Manitoba, Mennonite Church Manitoba, and the Mennonite Brethren Church of Manitoba—was modelled after a similar conference of the same name at Columbia Bible College in British Columbia in May 2018. Its purpose was to help participants be better equipped to prevent and respond to painful situations within the church.

The themes were tackled through worship, a panel discussion, plenary speakers and a number of workshops.

Sin, accountability and forgiveness

In the first plenary speech, Carol Penner, an assistant professor of theological studies at Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo, Ont., drew on the parable of the Good Samaritan to illustrate two different kinds of sin when it comes to abuse in the church.

The thieves sinned by beating and robbing the traveller, but she said there’s more to the story. “The story Jesus tells is of the religious leaders who walk by the hurting person,” she said. “The story is about not seeing the pain. That’s what Jesus points out in the story: It’s a sin to walk by their pain and to ignore them.”

Part of addressing the pain and harm done involves accountability.

Penner said that public charges must be laid against pastors who have committed abuse so they can’t lie about their past and go on to work in other environments with vulnerable people.

She added that forgiveness and accountability go hand in hand; however, forgiveness can’t be rushed: “If a church steps in at this early stage [before a church leader really understands the harm they did], and says, ‘We forgive you,’ no one has been helped. The victim feels like they’ve been erased.”

Likewise, she said the perpetrator may come to believe “they can abuse people and be immediately forgiven, they don’t have to face pain, they don’t have to feel the pain and they don’t have to be confronted about what motivated it.”

Becoming a victim- and survivor-affirming church

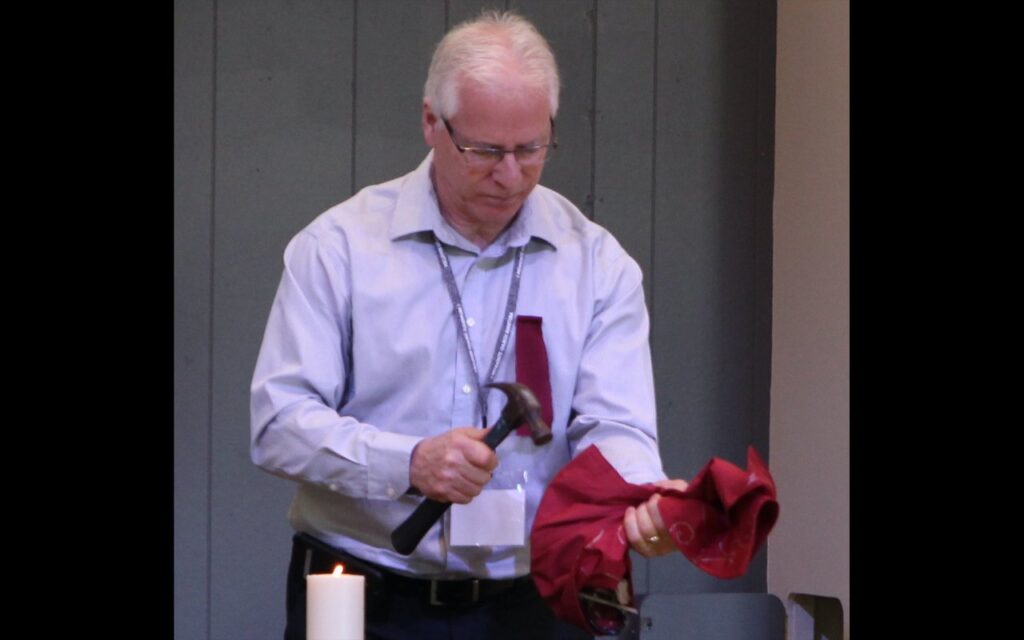

The following day, conference participants learned more about creating spaces that are affirming of victims and survivors. David Martin, executive minister of Mennonite Church Eastern Canada, spoke about confronting ministerial sexual misconduct.

During his 12 years at MC Eastern Canada, he has dealt with 12 cases of alleged misconduct in the church and has come to believe a fundamental attitude shift needs to take place to create a victim- and survivor-affirming church.

In his speech, he emphasized five key points. Changing the culture around sexual abuse means:

1. Victims need to be treated with respect, dignity and due process.

2. Resisting the knee-jerk reaction of blaming the victim.

3. The church must dismiss the notion that abuse allegations are the product of emotional instability.

4. Recognizing that emotional pain does not have an expiry date.

5. The church has to ensure the confidentiality of the victim is respected.

Martin added, “Sadly, this is not always the culture we have embodied in the church, and at times we’ve silenced the victim and minimized their stories.”

Shame and vulnerability

Carolyn Klassen, the director and therapist at Conexus Counselling in Winnipeg, spoke about how shame impacts every part of the abuse dynamic: from survivor, to perpetrator, to the surrounding community.

“Shame cannot survive without empathy,” she said. Therefore, when victims and survivors of abuse are treated with respect and empathy, their traumas are shared with others and they can process it better.

“The ones who are very affected by their trauma were left to deal with it on their own, and made to believe that the harm didn’t matter, or that they didn’t matter,” Klassen said in contrast.

However, shame doesn’t just impact the victims of abuse. She said that pastors are often held to high standards and don’t have the time or space to meet their needs in healthy ways.

“Asking for help creates community,” she said. “We need the support, love and care of others. Historically, churches haven’t allowed pastors to ask for help.”

Klassen said she advocates for church leaders to have their counselling subsidized by the church, and for pastors to be given overt permission to be “human” before they get to a place where they’re abusive.

In addition to the plenary speakers, Jaymie Friesen, the abuse response and prevention coordinator for MCC Manitoba, facilitated a panel of abuse survivors to help participants understand that abuse in the church isn’t a hypothetical situation, but it affects real people.

“There’s been so much silence surrounding this topic,” she said. “We as churches need to live up to what we’re called to do, and that’s to be a safe place, a healing place. These conversations have to happen so we can create change.”

Online resources for abuse response and prevention

Mennonite Church Canada abuse resources: commonword.ca/go/1423

MCC’s Abuse Response and Prevention website: abuseresponseandprevention.ca

MCC’s “Understanding sexual abuse by a church leader or caregiver”: mcccanada.ca/media/resources/1340

MCC’s “Home: A safe place for all”: mcccanada.ca/media/resources/1342

MCC”s “Abuse: Response and Prevention”: mcccanada.ca/media/resources/1343

Mennonite Church Eastern Canada’s “Sacred Trust” educational series: mcec.ca/sacredtrust

Further reading:

‘This is about us’

‘I’m sorry’: Apologies and abuse

‘This is a holy and good thing’

Broken boundaries

#ChurchToo conference tackles painful subject

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.