Janet Bauman recently participated in a 45-minute virtual tour of the former Mohawk Institute Residential School in Brantford, Ont., with other people from St. Jacobs Mennonite Church; it fit in with the congregation’s worship series on unlearning racism. Carley Gallant-Jenkins, who currently works as the Save the Evidence coordinator for the Woodland Cultural Centre, served as Zoom host for the evening.

It is an imposing structure. It was the first institution of its kind built in Canada and is one of the last remaining. It is nicknamed the “Mush Hole” for the oatmeal porridge that was served there, often three times a day.

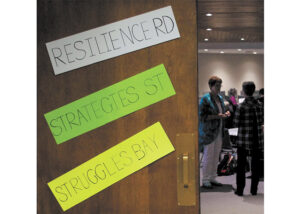

Other such buildings have been torn down. And yet this one will be preserved. Indigenous survivors insist on it. They call it “a monument for our resilience.”

Save the Evidence is a campaign to restore the former Mohawk Institute, and develop it as an interpreted historical “site of conscience” that will become the “definitive destination” for education about the experiences of survivors and the impact of the residential school system in Canada.

During the virtual tour, Lorrie Gallant provided the history of the institute and showed viewers the girls and boys dormitories, the cafeteria, laundry room and other features of the building. Along the way she and five survivors shared some of its stories.

Begun in 1828, the institute served as a boarding school for up to 100 First Nations children from Six Nations and other communities in Ontario and Quebec. “It served as a key tool in the effort to assimilate First Nations children into European Christian society and sever the continuity of culture from parent to child,” according to the Woodland Cultural Centre website.

It closed in 1970 but was reopened two years later as the Woodland Cultural Centre, to preserve and promote First Nations culture and heritage.

The assimilation of Indigenous children, as young as four, began when they walked up the front steps, according to Gallant. They were immediately stripped of their clothing, belongings and names. Boys had their heads shaved. Girls had their hair cut short. They were bathed in lye, given a uniform to wear and issued a number that corresponded to their bed, blanket and bowl. They were separated from siblings and punished for speaking their language.

Girls were assigned the domestic tasks of cleaning, cooking, sewing and doing laundry, and rarely went outside. Boys were assigned outdoor work, including farm chores, but were not provided with winter boots or coats.

There were alarms on all the doors, and children who were caught after escaping were placed in solitary confinement in the basement.

John Elliot recalled being sentenced to this space for two days and told how his friend slid bread under the door for him so he would have something to eat.

As the virtual tour through the building unfolded, Gallant recounted a litany of abuses and neglect. In the former cafeteria, she described how children were malnourished. Chickens and cows on the property produced fresh food that the children were not allowed to eat. In the infirmary, she said medications not yet approved for the public were tested on the children. In the girls bathroom, she explained that there were only three tubs and three towels for the 35 to 40 girls to take a weekly bath. Sexual abuse often took place in the laundry room because the noise of the machines hid any sounds. In the recreation room, staff would force boys to fight each other for entertainment, she said.

She showed Zoom viewers a spot, discovered during restoration, where children hid quilts and other belongings in a crawl space that they turned into a refuge. She showed them a wall at the back of the building where children etched their names into the bricks as a way to preserve their identity.

Roberta Hill, a survivor, spoke of the significance of preserving the site: “History needs to be told by the people who experienced it. We are not lying to anybody. We’re trying to tell you what happened in that time period.”

Gallant-Jenkins said survivors played a key role in saving the building, and they are playing a key role in planning how their stories will be curated. There are some survivors, she said, who can’t come back to the building yet, as it is still an “open wound” for them.

Geronimo Henry said, though, that he has moved from anger to healing by sharing his story.

Well over 50 of these virtual tours have raised more than $23,000 toward the restoration.

The total budget for the project is $23.5 million. So far, $12 million has been raised. The Woodland Cultural Centre is awaiting a funding request for $11 million more. If that is secured, $500,000 will remain to be raised to complete the project and allow it to open to the public in June 2022, on the centre’s 50th anniversary.

Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Eastern Canada? Send it to Janet Bauman at ec@canadianmennonite.org.

Related story:

Building relationships with residential school survivors

LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0geyBtYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAzMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbiB7IGJvdHRvbTogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcik7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDAgMCA1cHggMDsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IHVse2xpc3Qtc3R5bGU6bm9uZTttYXJnaW46MCAwIDEuNWVtIDA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse21hcmdpbjowICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3RvcDowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHtncmlkLXJvdy1lbmQ6dW5zZXQgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6OmJlZm9yZXtjb250ZW50OiIiO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3BhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxsOjptYXJrZXJ7Y29udGVudDoiIn0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgaW1ne2hlaWdodDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7d2lkdGg6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7YWxpZ24tc2VsZjplbmR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczpyZXBlYXQoMTIsIDFmcil9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1jb2xsYWdlIGltZ3toZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MDtncmlkLWF1dG8tcm93czoxcHg7b3BhY2l0eTowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgaW1nLC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpZnJhbWUsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHZpZGVvey1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt3aWR0aDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7ZGlzcGxheTpibG9ja30udGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbntwb3NpdGlvbjphYnNvbHV0ZTtib3R0b206MDt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjYpO3BhZGRpbmc6NXB4IDJweDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtjb2xvcjojMzMzfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uOmVtcHR5e2JhY2tncm91bmQ6dHJhbnNwYXJlbnQgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgZmlndXJle2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IGltZ3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDoxMDAlOy1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjpib3R0b219I2xlZnQtYXJlYSB1bC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5e2xpc3Qtc3R5bGUtdHlwZTpub25lO3BhZGRpbmc6MH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uIHsgYm90dG9tOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHsgcGFkZGluZzogMCAwIDVweCAwOyB9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb24geyBib3R0b206IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgeyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgeyBwYWRkaW5nOiAwIDAgNXB4IDA7IH0gIH0g

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.