“It’s personal, there are names and faces. It’s not just textbook information now.”

That’s how Timothy Khoo, 16, describes what it was like to meet residential school survivors while volunteering with Mennonite Disaster Service (MDS) at the former Mohawk Institute Residential School in Brantford in July.

Khoo was one of 13 youth and leaders from Toronto Chinese Mennonite Church who spent the last week of July at the school building desks, tables and benches for a representative classroom and dining hall at the school that was in operation from 1828 to 1970.

The volunteers from the Toronto congregation also helped moved thousands of books and files back to the library, while volunteers from other churches restored a replica longhouse, which is used for educational purposes.

Altogether, 61 youth and leaders from Mennonite churches in Toronto, Kitchener, St. Jacobs, Listowel and Elmira, Ont., and Abbotsford, B.C., participated in the MDS summer youth project.

This year, the project was done in partnership with Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Ontario and the Woodland Cultural Centre, which operates on the site of the former residential school.

Stella Liu, 13, says the experience was “more in-depth than what we learned in school, more emotional. I never knew how bad residential schools were.”

Jim Zhang, 16, says, “It’s great to do something to make up a bit for what happened to Indigenous people. It gives me satisfaction to do something good.”

A testament to the horrors

Over the school’s 142-year history, thousands of children from the nearby Six Nations of the Grand River, and other First Nations in Canada, were sent to the Anglican Church-run school. While there, they were stripped of their language and culture. Many also experienced physical and sexual abuse.

When it closed, the school was returned to the Six Nations of the Grand River, which uses it as a cultural centre, library, archive and office space.

In 2014, a storm severely damaged the building, rendering it unusable. The community was asked whether to tear it down or save it. An overwhelming majority voted to restore it as a testament to the horrors that happened there.

To realize that goal, Woodland launched the Save the Evidence campaign to restore the building. Through it, grants were obtained from various levels of government to do major repairs. But assistance was still needed to complete the exhibits.

In 2016, Woodland asked MCC if it could help. “We were honoured to receive the request and asked MDS to partner with us,” says Lyndsay Mollins Koene, who coordinates MCC Ontario’s Indigenous Neighbours program.

Nick Hamm, MDS Ontario’s unit chair, realized it wasn’t a normal request for the organization, which usually helps following natural disasters like floods, fires, earthquakes and storms. “It’s not a typical MDS disaster response,” says Hamm, “but residential schools were a disaster for Canada’s Indigenous people.”

For Carley Gallant-Jenkins, Woodland’s campaign coordinator, “it was surreal” to see all the work done by the volunteers. “We’ve been dreaming and planning about this since 2014,” she says, surveying the desks, benches and tables built by the youth. “There’s still lots to do, but the work of MDS and MCC is helping us reach our goal.” The furniture “will help set the tone for the space, showing what it was like when children were sent there.”

The dining hall restoration is particularly poignant since siblings who were sent to the school were separated and not allowed to talk to each other. While eating, they couldn’t talk to each other, “but at least they could see each other from a distance,” Gallant-Jenkins says.

She realizes it wasn’t easy for the youth to hear stories like that. “They were hard stories to hear, but so important if we are to move forward together,” she says.

‘I find it hard to forgive’

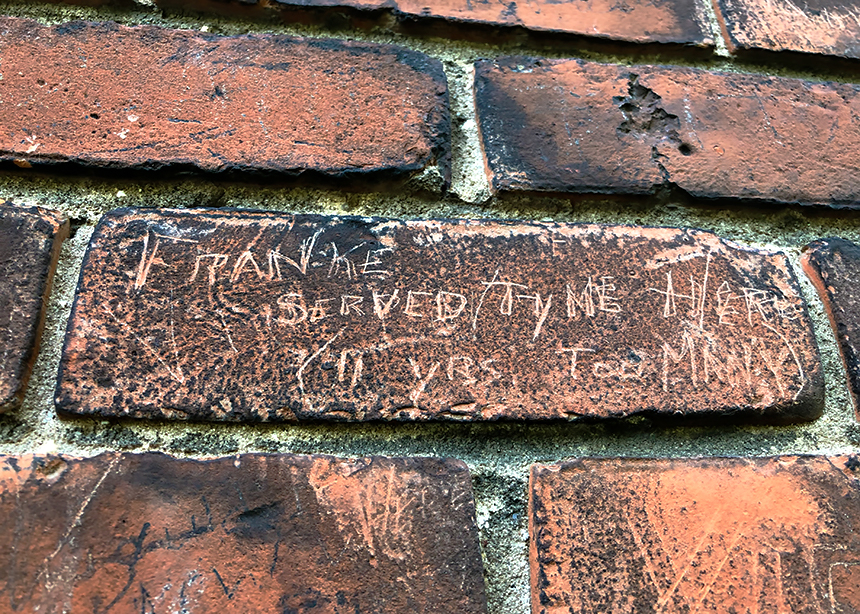

Geronimo Henry, 82, attended and lived at the school for 11 years, from 1942 to ’53. He started when he was 5.

“It was pretty hard,” he says of his time at the school. “I was lonely and sad.”

In all the years he lived and studied there, “nobody ever said I love you, nobody hugged me, nobody tucked me in at night,” he says. “I never had any of that.”

He was also forbidden to speak his language. “They wanted to assimilate us into the dominant society,” he says. “I lost my ability to speak it.”

Henry wasn’t abused at the school, although he got the strap for things like playing when he was supposed to be in bed. “We were all abused, in a sense,” he says, “mentally, physically, emotionally.”

The lack of love and parental guidance meant he was unprepared for life when he left the school. This included raising his own children. “You can only practise what you’ve been taught,” he says. “Nobody taught me how to love and be a good parent. I was dysfunctional.”

Of his experience at the school, “I find it hard to forgive,” he says. “It took my childhood from me.”

One way he finds meaning is by sharing his story with others, like he did when the MDS youth project volunteers were on site. “I ate at a table like this,” he says, sitting at one of the tables the volunteers had built, his hands running over the polished wood. “I really appreciate what MDS did. It was great to meet each group, tell them my story and learn about them.”

‘A long journey’ completed

For Nick Hamm, the end of the project was also the completion of “a long journey.”

Getting it off the ground took a long time, but “it’s worth it when you see the end product, both the furniture and the books, but mostly the relationships the volunteers developed with survivors and staff at Woodland,” he says. Altogether, those people “gave us a blessing. Now it is up to us to do something with what we learned there.”

“The project was steeped in a story we are a part of,” Mollins Koene says, referencing Mennonite involvement in running at least three residential schools in Ontario. It was also about “more than restoring a building. It was about restoring relationships between nations and between individuals.”

This article appears in the September 16, 2019 print issue, with the headline “‘More than restoring a building.’”

Related stories:

Hurricane Dorian: MDS is “ready to respond”

Watch: ‘Gettin’ it done’ with MDS

Canadian faces of MDS in Texas

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.