It’s been 40 years since David battled Goliath on the plains of Saskatchewan. David, in this case, was a group of ordinary citizens, many of whom were Mennonite, and Goliath was the nuclear industry.

In 1976, when the Saskatchewan Economic Development Corporation optioned to purchase 583 hectares of agricultural land east of Warman, Sask.—about 25 kilometres northeast of Saskatoon—residents were told the land might be used for a shoe factory.

Eventually, they discovered that Eldorado Nuclear, a federal crown corporation, planned to set up a uranium hexafluoride refinery, which would turn yellowcake, a refined form of uranium ore, into fuel for nuclear reactors.

It didn’t take long for residents, many of whom were Mennonite, to become concerned about what they saw as a threat to their faith and their way of life.

Ernie Hildebrand was a recent graduate of Canadian Mennonite Bible College (CMBC), a precursor college to Canadian Mennonite University in Winnipeg, when Osler Mennonite Church hired him as its pastor. Osler is about eight kilometres north of Warman.

“I was 31 or 32 when this hit,” he says. “When I left CMBC, I didn’t [intend] to be an activist pastor, but people asked, ‘What’s your church going to do?’ So I got involved.”

Hildebrand and several congregation members invited the community to a meeting to discuss the proposed refinery. This group eventually became the Warman and District Concerned Citizens Group, with Hildebrand serving as chair.

Other core members included vice-chair Nettie Wiebe, Jake and Louise Buhler, Leonard Doell, and Edgar Epp, who would later succeed Hildebrand as chair.

Over the next five years, group members educated themselves and others about the uranium industry. They published articles in the local newspaper and visited neighbouring Bergthaler and Old Colony Mennonite communities, speaking with them about the proposed refinery. They travelled throughout Saskatchewan, across Canada and even into the United States, speaking and leading workshops on the nuclear industry.

Over time, the group grew to upwards of 500 registered members. But while it gained supporters, it also had opposition.

Eldorado courted town and rural municipal councils, flying them to Port Hope, Ont., to tour the nuclear refinery there. Many were won over by the promise of jobs and revenue for their community. With Eldorado’s encouragement, they formed the Warman and District Informed Citizens Group.

“The issue divided the community into ‘concerned’ versus ‘informed,’ ” says Doell. “There were very strained relationships within families and between community members.”

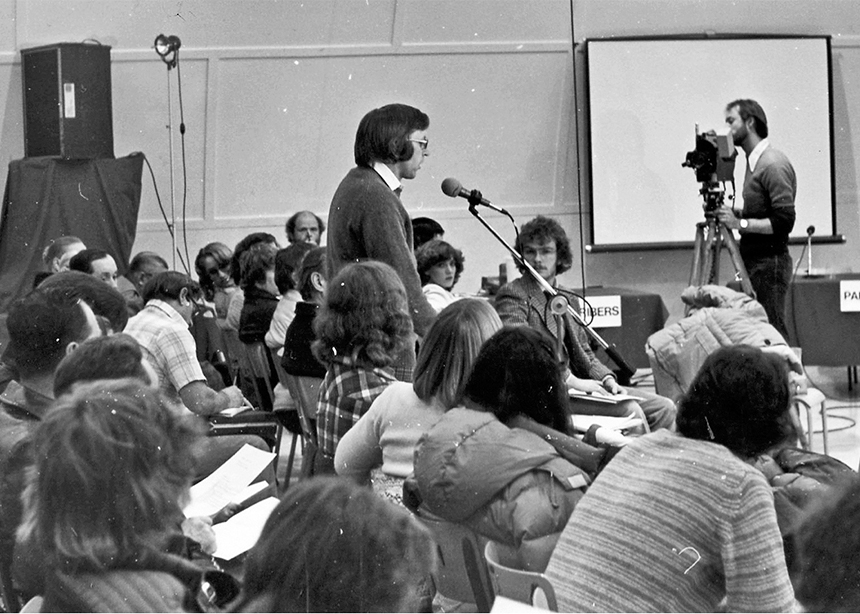

The five-year struggle culminated in January 1980 with three weeks of hearings before the Federal Environmental Assessment Review Organization (FEARO).

The citizens group was told it could testify, but that it should choose one individual to act as its spokesperson. Instead, it invited as many people as possible to testify. There were expert testimonies, including that of David Schroeder, a CMBC professor, but most were just ordinary citizens: farmers, teachers, pastors, high-school students, businesspeople, environmental activists and Indigenous people.

“What got us the victory was we identified who we were,” says Jake. People talked about their faith, their values and their way of life.

It took until the spring of 1981 for FEARO to announce its findings. The environmental panel concluded that Eldorado’s proposal was technically and environmentally sound, but that the corporation hadn’t considered the impact of a refinery on the mainly Mennonite community. It would need to complete such a study for its project to be approved.

Eldorado withdrew its proposal within a week, returning the land to its previous owners.

Looking back

Former citizens group members recall their battle against Eldorado as a time of high emotion and tension.

“In the months preceding the hearings, we felt that our phones were being tapped,” says Jake. “It was so tense. The stakes were so high that we felt the world was against us.”

Hildebrand, who calls it being “all-consuming,” left his pastorate at Osler Mennonite to give himself full-time to the work of opposing the refinery.

And when it was all over, many of the members felt exhausted.

“We were so fatigued after five years of struggle,” says Jake. “We didn’t meet as a committee after that.”

In spite of this, these former activists still feel they did the right thing and that the struggle was worth it.

“I’m still enormously gratified that we were able to mount that kind of resistance with the methodologies that we used,” says Wiebe. “The Warman experience, for me, illustrated just how complex—but also how effective—grassroots, democratic organizations can be.”

Doell echoes her thoughts. “We fought a giant,” he says. “Everyone said that it couldn’t be beaten. But if people work and stand together, you can actually effect change, no matter how big that beast looks.”

Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Saskatchewan? Send it to Donna Schulz at sk@canadianmennonite.org.

Related story:

MWC signs statement against nuclear weapons

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.