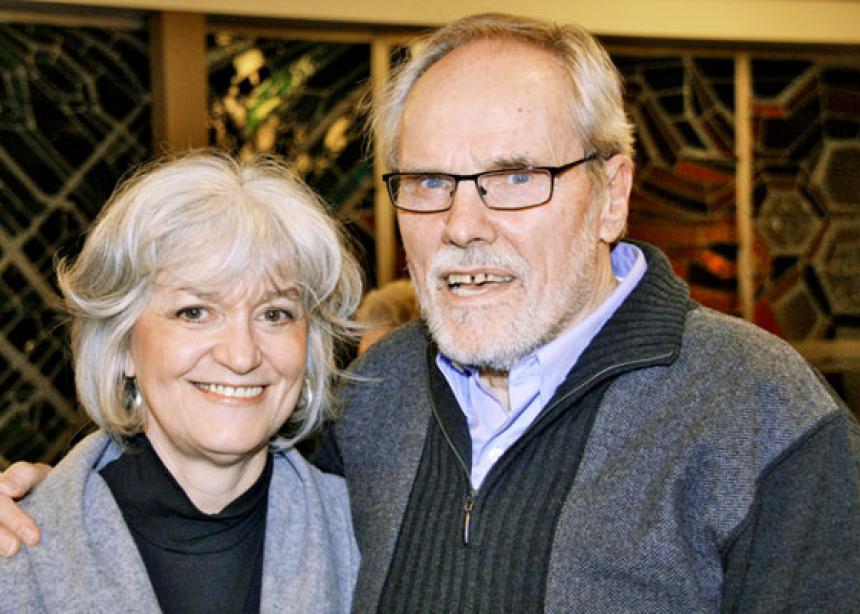

During a recent interview focusing on his debut novel and recent CMU Pax Award, acclaimed Mennonite writer Rudy Wiebe spoke on a variety of topics, including Omar Khadr, Miriam Toews, the western Canadian Indigenous story and the MB Herald.

Here’s what he had to say.

First book leads to unexpected friendship

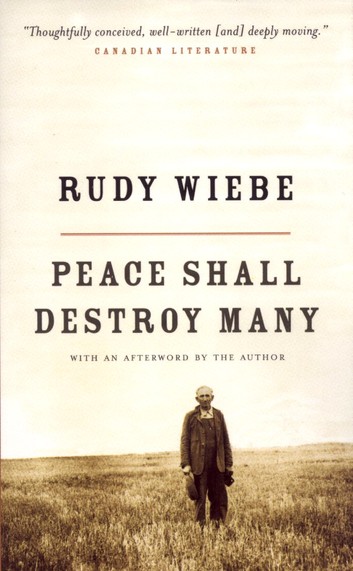

One unexpected result of Wiebe’s first book, Peace Shall Destroy Many, is his friendship with Omar Khadr, the Canadian who was imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay for committing war crimes in Afghanistan.

Khadr, who was 15 at the time, was taken there by his father, an extremist who was part of al-Qaeda.

While he was in prison at Guantanamo Bay, professors at Edmonton’s King’s University helped him get a high-school education. One of the books they gave him to read was Peace Shall Destroy Many.

“Omar liked it and wrote me a long letter about it, and so we start corresponding,” says Wiebe.

When Khadr came to Canada, he was sent to a prison in Edmonton where Wiebe went to visit him. “We had a number of conversations through the prison glass,” Wiebe says. “Through that, our friendship and our understanding of each other grew. It’s quite wonderful.”

As for why Khadr liked the book, Wiebe says he saw in it how a person could “struggle with the teachings of a father . . . being dominated by an overwhelming patriarch and getting into real difficulties over it.”

Of course, his experience was “far more drastic,” than for the characters in his book, Wiebe observes.

As for Khadr today, Wiebe says, “He strikes me as a wonderful man. I have always marvelled at how little anger he has.”

Rudy Wiebe on Miriam Toews

If Rudy Wiebe is the father of Mennonite writing in Canada, the best-known Canadian Mennonite writer today is Miriam Toews.

That was all-but-confirmed last month when Toews was profiled by The New Yorker in an essay titled “A beloved Canadian novelist reckons with her Mennonite past.” The subtitle was: “How Miriam Toews left the church and freed her voice.”

As author Alexandra Schwartz put it, “Her fiction has often dealt with the religious hypocrisy and patriarchal dominion that she feels to be part of her heritage, and with a painful emotional legacy, harder to name but as present as a watermark.”

Like with Wiebe, Toews’ work has provoked angry reactions from some Canadian Mennonites.

In response, she told The New Yorker, “It’s not a critique of the Mennonite faith or of Mennonite people but of fundamentalism, of that culture of control.”

Wiebe took on similar themes, and received similar backlash. Unlike Toews, however, he never left his faith nor lost his appreciation for the Mennonite church.

While praising Toews, whom he considers a personal friend, he says “The kinds of things she writes about Mennonites, I don’t write that way about them.”

He regrets that her view has come to be seen by many as representing what all Mennonites in Canada are like, “as if there is only one sort of Mennonite world. That’s a problem for me.”

At the same time, he defends her right to speak critically of her experience of the Mennonite church, something she wrote about in Granta in 2016.

In the article, she recalled a speaking tour she did with Wiebe in Germany in 2008. The tour included presentations for some conservative Mennonites in that country. At one presentation, in Detmold, an angry Mennonite woman confronted Toews, saying her 2004 novel A Complicated Kindness was “filthy and that my characters’ mockery of Menno Simons, the man who started the Mennonites in Holland 500 years ago, was sacrilegious and sinful.”

Wiebe came to her defence. “What I’ll remember is that on that day Rudy Wiebe stood up in front of a Mennonite ‘congregation’ and fought for me,” she wrote. “Rudy had defended me. . . . He said that the reaction to my book had reminded him of the Mennonite reaction to his first novel, Peace Shall Destroy Many.”

Wiebe remembers the incident well. “The woman said I would not allow my 16-year-old daughter to read that book,” he recalls. “I said if she didn’t want her children to read it, that’s her right to say that. But she couldn’t say that to anybody else.”

Like Toews wrote in Granta, Wiebe remembers the woman was not satisfied by his explanation, angrily storming out of the room.

Telling the western Canadian Indigenous story

In addition to writing about Mennonites, Rudy Wiebe is also well-known for his books about Indigenous people in western Canada.

He traces that interest to growing up on the northern prairies, “so close to the land.”

When his family and other Mennonite refugees from the former Soviet Union showed up in northern Saskatchewan in the 1930s, he says the land was considered “empty because nobody had farmed it before. But they [Indigenous people] were there the first, using it in a different way.”

But he soon realized “there was no question they had lived there for a long time before we refugees showed up. This was intriguing to me.”

As a boy, he enjoyed wild saskatoon berries and strawberries, knowing “these have been eaten by 500 generations of Indigenous people before me. But I enjoyed them just as much as they did.”

His interest in Indigenous people led him to want to write books about them. “What I basically was trying to do was tell the story of what happened to them, a story that that basically had never been talked about in western Canada before,” he says.

Of his 1973 book, The Temptations of Big Bear, he says “I don’t think there had been a book from an Indigenous standpoint” until it came out, where the Indigenous character is “the hero of the book.”

Until then, he says that Indigenous people were “stereotyped basically, either romanticized or portrayed as down and out, poverty-stricken addicted people, on the fringes. Certainly never worthy of being the protagonists of a major work of fiction.”

He is sensitive to the issue of cultural appropriation, but says Indigenous people have always told him, “If you treat us with respect and know what you’re writing about, go ahead and do it.”

Besides, he adds, that was a different time. Today, there is no need for non-Indigenous people to write about Indigenous people since they have “so many good writers of their own.”

Wiebe’s experiences with Indigenous people have also influenced how he sees his own faith.

“I can’t believe that the God who created the world would just give one little vision [of himself] to one small group of people in the Middle East and keep everything else hidden from everyone or every human being all over the Earth,” he says. “That’s not from the kind of God I understand.”

He also believes that Mennonites are well placed to be empathetic towards Indigenous people, due to their own history of being displacement and refugee flight.

Noting how many Mennonites, including his own family, were forced off their land in the former Soviet Union in the 20th century, “You start thinking about what it would be like for someone to invade your country, and taking over your home. . . . These are profoundly the same issues.”

Time editing the MB Herald ‘formative’

Rudy Wiebe’s time as editor of the Mennonite Brethren Herald was short—just about 18 months—but he enjoyed his time there.

“It was great,” he says, recalling he got his first plane trip because of it when he flew to Ontario for the Mennonite World Conference in Kitchener, Ont. in 1962. “I did the kinds of things that reporters do at an event like that: interviewing people, taking photos.”

Although he went on to fame as a novelist, Wiebe says that his time at the Herald was formative for his writing. “It helped me in researching and writing,” he says. “It gave me very practical experience in terms of interviewing people and digging for information.”

He’s still proud of the issues he edited way back then. He still has them in his office. When he looks at them today, he says, “I can see how I was learning as I went along.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.