I stand on the very spot where it all began, in a former Catholic church in the village of Pingjum, Netherlands. Here, the priest Menno Simons was called to account by his superiors.

He’d been interpreting scripture for himself, pondering deeply the words of the prophets, of Jesus, of the apostles. Menno rejected the dogma of his church superiors. He began teaching adult baptism, and that works must accompany faith. He was branded a heretic and spent the rest of his life in hiding.

I visit the Pingjum church while in the Netherlands for a meeting of the Mennonite World Conference (MWC) executive committee in late 2022. As I stand where Menno stood—amidst meetings with Mennonites from around the world—I think of how his teachings, and those of other early Anabaptists, have travelled across generations and geography

Today, Mennonite World Conference reports more than two million Mennonites in over 86 countries. As I pause in that little church, I’d like to ask Menno: “Did you have any idea? Did you know what would happen when you set down that chalice for the last time and walked away from the official priesthood?”

As travel restrictions eased in 2022, I accepted five invitations to visit places Menno’s teachings have reached over the last 500 hundred years. I travelled as part of my job, but it was more than that. I wanted to feel like a humble and open-minded pilgrim. I yearned to be transformed.

Indonesia

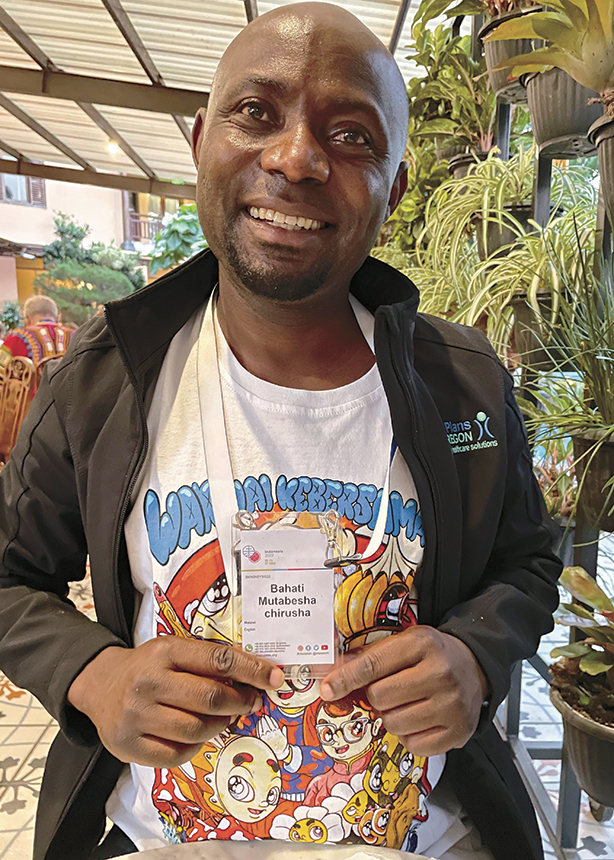

My pilgrimage begins with the Mennonite World Conference assembly in Salatiga, Indonesia last July. Sobering testimonies rend my heart. I met Safari Mutabesha, the son of a Congolese Mennonite Brethren pastor. He witnessed a rebel murder his father in the family home.

Forced to leave Congo for his own safety, Safari ended up in refugee camp in Malawi. He became a preacher in the camp. There, he met the commander in charge of the brutal operation that killed his father. The camp residents know this man, fear him. Safari invited the man to live with him, which he did for three years, during which time Safari ministered to him.

The former rebel commander is now a Mennonite pastor in Malawi. In many ways, the story is far removed in time and space from Pingjum, but in other ways it is not.

Ethiopia

I’m barely back home when my phone pings with a calendar reminder to prep for a trip to Ethiopia with colleagues Norm Dyck and Fanosie Legesse. I briefly question my sanity: Who willingly goes to a country engaged in civil war? But after two years of travel restrictions, international partners are eager for connection.

The Ethiopian invitation nudges at my inner preacher; I recollect the apostle Paul in Philippi. He discovered some women by a river with open hearts for God. They became co-founders of a church Paul deeply loved.

In Ethiopia, there are not just a few believers by a river, but a vast, flowing river of believers. I’m told the Meserete Kristos Church (MKC) baptizes 25,000 people per year, many of them young. Leaders are frustrated by this “slow” pace of growth. There is such a hunger for the gospel right now and church members could be doing more than they are to share it.

I speak with pastor Endezinaw Tefera at the Asela church in the mountains south of Addis Ababa, the capital. For 20 years he wrote sermons on his lap because he had no desk. The people of his church met under tarps held up by poles, delaying building plans in order to devote energies to church planting. This one congregation has planted 47 churches and there are 10 more getting started.

On my trip to Ethiopia I learn that more than 40 Mennonite church buildings in the western part of the country have been burnt down, caught in the middle of ethnically charged violence; some 57 pastors displaced. Yet their people still meet, sometimes under trees next to charred buildings, and they still contribute financially to the conference.

I meet a man back in Addis Ababa who became a street child at age 11. For many years, he had only one aim in life—to return home and kill his abusive father. At the persistent urging of some local Ethiopian Mennonite missionaries, he attended a worship service one evening, and as the choir sang the love of God washed over him in a way that words fail to describe. Today, after years of healing and study, he is one of the key leaders in MKC.

Dyck, Legesse and I ask a group of 50 regional leaders of MKC about their key to growth. “Prayer,” they say, “followed by miracles, strategic evangelism and discipleship teaching.” It all hinges on prayer.

Philippines

The next leg of my pilgrimage leads me to Mindanao province in the Philippines where I meet up with International Witness workers Dann and Joji Pantoja. They lead Coffee for Peace and Peacebuilders Community Inc. (PBCI).

We pull up to a coffee shop; its slogan reads, “Just coffee in every cup.” The wordplay on “just” carries a deeper meaning here. The Philippine military has been in a long-term conflict with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, a group seeking autonomy from the central government. The tensions make life difficult for coffee farmers.

We drive into the mountains where two Indigenous tribes grow coffee. They’ve been caught up in the fighting, trying to eke out a living while fearing for their lives. Safe travel is no guarantee. We’ve sent pictures of our vehicle in advance, alerting guerilla snipers that we are not a threat.

Over a dozen elders welcome us. We are safeguarded by a local power utility with security responsibilities. After introductions come immediate questions: “Are you here to plant a church?”

“Only if you want us to,” I reply. Applause.

I learn about the challenges they face in growing and selling their crops. I learn how PBCI and Coffee for Peace can provide assistance. We share a feast of locally grown delights with names I cannot pronounce.

We visit another tribe, another elder. Here, a pair of large metal leaf sculptures and a plaque memorialize the names of the 39 people—including 22 children—killed in the 1989 Rano massacre. Those killed were part of a United Church of Christ group that had gathered for worship. The day before the massacre, the Indigenous group had rejected demands from armed revolutionaries of the Communist Party. The massacre was their response. I cannot imagine the pressure they faced. I listen to stories from survivors and descendants of the victims. Buried emotions rise to the surface, a visceral testimony to the deep wounds that remain.

At a military checkpoint on our way back out of the mountains, Dann and our driver are questioned intensely. I learn that the tinted windows in our van triggered concerns we were being kidnapped. The next day an army colonel, decked out in army fatigues, visits us at the PBCI office. His men wait outside.

We chat congenially until he leans in close and picks up a booklet from the table. It’s a PBCI training text. He has a request: “I have come here today to seek permission to use what is in this book to train our soldiers in peacekeeping. What you as a Mennonite Church do is far more effective at building and maintaining peace than the approach of the army.”

Many wise men and women did the heavy lifting in developing the booklet, drawing on the peace teachings of Menno Simons and Jesus. The teaching is a gift to the church. Now it is a gift to the world.

Japan and Thailand

I head to Japan and Thailand in January 2023, the last leg of my six-month pilgrimage. In Thailand I join a Mennonite Church (MC) Canada learning tour focused on the work of International Witness workers Tom and Christine Poovong. They’ve established the Friends of Grace network, a rapidly growing group of churches hungry to learn about Anabaptist principles. We’ve brought a suitcase full of translated copies of Palmer Becker’s book, Anabaptist Essentials. Menno is here, too.

In Japan, I meet Menno again. Witness workers Gerald and Rie Neufeld from Canada take me to the Tokyo Anabaptist Centre, and into an unlit, unheated room that houses its library. We poke around with flashlights.

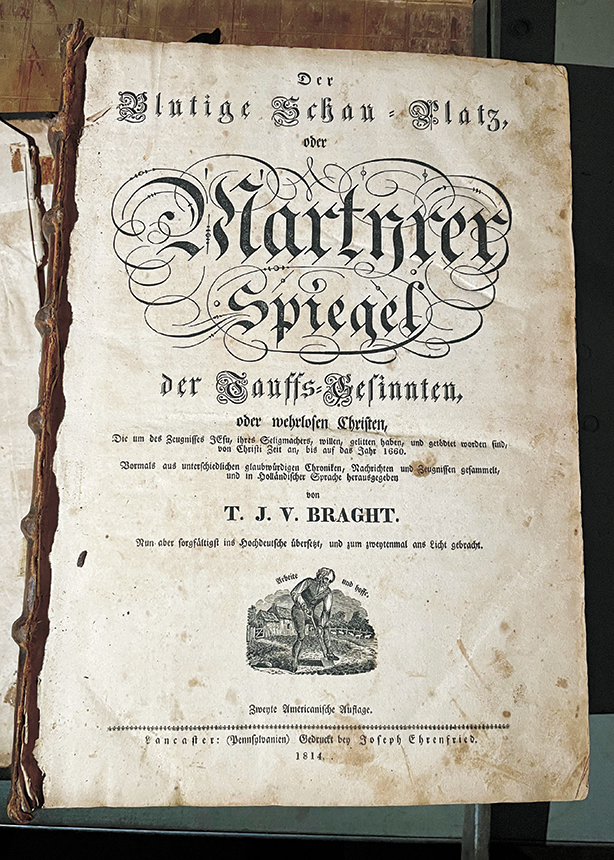

High up on a shelf I spy a large, fat book. Could it be? I open the cover, astonished to read its title in German Gothic Script: Martyrs Mirror. It is a leather-bound 1814 edition.

MC Canada has had a long relationship with Mennonites in and around Tokyo, but perhaps Menno Simons has been here longer.

My mind races back to the Haarlem Mennonite Church in the Netherlands. I preached there two days after my visit to Pingjum. At the Haarlem church, three members showed me their ancient leather-bound copy of the same Anabaptist classic I saw in Tokyo. I was overwhelmed. In that moment, the work suddenly shrunk down to one huge intercultural Mennonite family.

These past months, I followed in the footsteps of the many faithful, some who gave their lives. I found evidence of Menno Simons everywhere, even some “relics,” in a sense. More importantly, in every place I went, I found the Spirit of God we have come to know in Jesus Christ.

As I wish I could ask Menno what he thinks about his teachings filtering down to all these people I also want to ask what we as Mennonites in Canada are doing in our own neighbourhoods to extend the peace of Jesus Christ as Menno and many others have done so courageously.

Doug Klassen is Executive Minister of Mennonite Church Canada, based in Winnipeg.

For discussion

1. If you were making a faith pilgrimage, what significant place would you choose to visit? How would you travel there? What would you hope to do or learn there?

2. Doug Klassen tells the story of a former rebel commander who became a Mennonite pastor. How is this story similar to that of Menno Simons? How is it different?

3. What do you find most amazing about the believers of the Meserete Kristos Church in Ethiopia?

4. What are some lessons we could learn from the Peacebuilders Community Inc. in the Philippines?

5. What are Mennonites in Canada doing to “extend the peace of Jesus Christ”? What should we be doing?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.