The correlation is unavoidable. Some of the areas with the lowest vaccination rates in Canada are areas inhabited by lots of Mennonites.

The Globe and Mail reported on vaccination resistance in the Aylmer area of Ontario, with special mention of Mennonites.

The southern Manitoba city of Steinbach made national headlines for a COVID-19 spike and church-led anti-restriction protests. The city is so German-Russian Mennonite that not only does the mayor have a German-Russian last name (Funk) but his office is on a street with another such name (Reimer Avenue).

The Rural Municipality of Stanley in southern Manitoba, where I live, appears to have the lowest vaccination rates in the country (at press time, 22 percent of those over 12 had at least one dose). And German-Russian Mennonites are surely the dominant group here.

Winkler, a small, heavily-Mennonite city surrounded by the municipality of Stanley, has also made headlines as a hotbed of vaccine and mask intransigence. Even during the height of lockdown, I visited many businesses in which not even staff wore masks.

We Mennonites are clearly not “all in it together” with everyone else. No, of course it is not only Mennonites, and not generally Mennonite Church Canada Mennonites, but somehow the Mennonite heritage has proven fertile ground for people who respond to this pandemic with a focus on personal freedoms and a preference for conspiracy theories over medical advice.

The social toll of this is significant. Martin Harder, Winkler’s longtime mayor, told the Winnipeg Free Press that differing views on COVID-19 are “breaking families apart,” as well as churches.

After hearing of an MC Eastern Canada congregation that expects to lose members who disagreed with COVID-19 restrictions in church, I wondered about the extent of pandemic-induced division in other churches.

So I talked to representatives of 10 MC Canada congregations:

- Two urban churches—one in BC, another in Winnipeg—reported no discernible tension. Everyone is on board with restrictions.

- A pastor in rural Saskatchewan said there are a handful of people in the congregation not coming because of risks posed by members who are not vaccinated. And some unvaccinated people are not coming because they feel like they are being treated like “lepers.”

Despite the sometimes “all-consuming” nature of COVID-19 and the uncertainty ahead, this pastor has an energetic attitude about the church’s future.

The other pastors I spoke with are in four southern Manitoba communities:

Corey Hildebrand is pastor of family ministries at Emmanuel Mennonite in Winkler. The leadership at Emmanuel has chosen to promote vaccination, offering people rides to vaccine clinics and speaking about it from the pulpit and to the media.

Still, Hildebrand is open about tensions within the congregation. While those tensions are “manageable,” he said there are differing views that will not change. And then there is the awkward uncertainty of not knowing where some people are at.

“I would expect that we have lost people,” Hildebrand said of members who may not return due to COVID-19 tensions.

With government-mandated restrictions now lifted in Manitoba, churches must decide what approach to take. These can be charged decisions.

After speaking to the Winnipeg Free Press about COVID-19 in May, Hildebrand said some local pastors contacted him privately saying they “wished they could have” spoken out publicly. When asked how he felt about this, Hildebrand acknowledged the importance of the backing of the leadership at Emmanuel and also noted that those other pastors could have had influence if they would have spoken up.

As for wearing the “Menno & Vaccinated” T-shirt someone gave him, you probably won’t see him in it around town.

Such is the climate in this area, where donning a mask is a loaded action.

Another southern Manitoba pastor said views in his church span the spectrum, although the majority are vaccinated. (Due to the sensitivity of the subject matter, I’m only naming pastors who have spoken previously to the media.) This pastor said that 90 percent of people are probably fine with getting back to normal. But, he said, the measuring stick for the church is how we treat the weak and vulnerable.

“There’s a small group in our congregation who are still very much at risk,” he said. And some are not vaccinated due to fear of being ostracized by family and friends not part of the congregation.

“I default to Scripture,” he said, quoting Philippians 2:3: “Do nothing out of selfish ambition.” He sees COVID-19 precautions as an opportunity to live out faith by putting the good of others ahead of individual freedom.

The leadership group in his church has spent much time discussing what to do now that government restrictions have turned into recommendations. It was easier, he said, when they could simply default to government requirements. Now, he said that “discernment is a moving target,” with ongoing revision and revisiting required as the situation changes.

This pastor spoke about a “spirit of divisiveness.” He asked: “How do we respond when this spirit enters into our homes and churches?”

He believes it is essential to listen to everyone. “People need to be heard,” he said, and also appreciated. Then he graciously seeks to involve people in the complicated practical decisions required within the church context. Differing voices must be considered, various interests must be acknowledged, and the well-being of vulnerable people needs to factor in.

He told of an older woman saying to him, “I’m so glad we wore masks last Sunday; I feel more comfortable going to visit my husband in hospital now.” People do not always consider those sorts of scenarios.

Mark Tiessen-Dyck, lead pastor of Altona Bergthaler Church, wrote a piece for the local paper encouraging people to get vaccinated as an expression of love for their neighbours. He said the majority of people in his congregation are vaccinated and have accepted restrictions. His article was intended more for others: “My goal was to write for people in churches where pastors are not saying anything, or people who hear church leaders discourage [vaccinations].” He wanted them to have another explicitly Christian view to consider.

Tiessen-Dyck is sensitive the downsides of pastors taking sides on divisive matters, but he felt this was a time when he needed to be clear on what he believes.

Another southern Manitoba pastor said that members express frustration with inconsistencies in government restrictions, such as exceptions or big-box stores, but are still willing to follow the rules in church. He said he is going with the advice of doctors, although he added that health-care professionals in his church differ on how strenuous restrictions should be. He said there have been disagreements but, overall, he noted a good amount of healthy conversation and understanding. “People recognize their mutual exhaustion and frustration,” he said. The isolation has been hard.

One pastor talked of friends who have a toddler with cystic fibrosis. They won’t risk public gatherings, so their daughter has never been to church activities. She is growing up not knowing what church is.

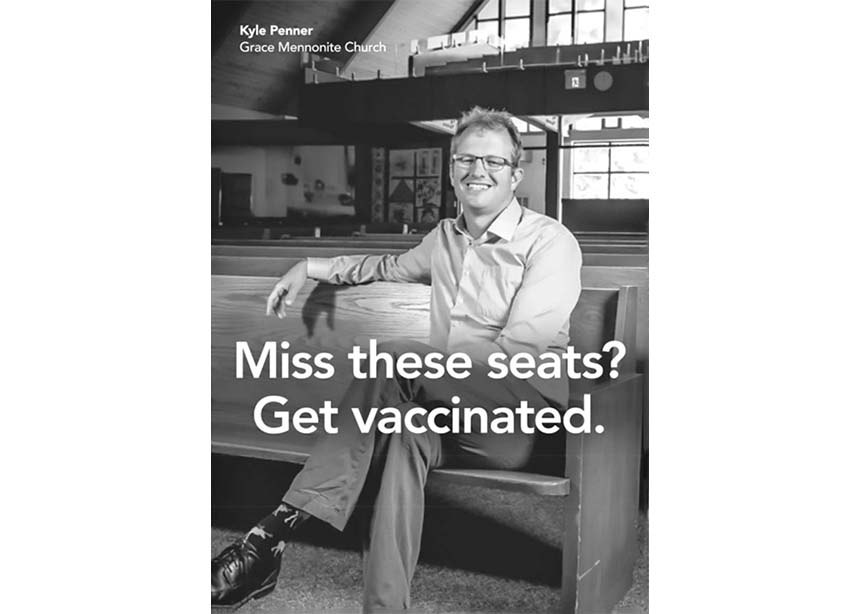

Kyle Penner is another pastor who has made his views public. He is assistant pastor of Grace Mennonite in Steinbach. He is also the Mennonite poster boy for vaccinations. Literally. Penner is on the advisory committee for Protect MB, the provincial government’s COVID-19 outreach initiative.

“I think there’s a role for the church to save lives, protect the vulnerable, protect the immunocompromised [and] support health-care workers,” Penner said.

He has the backing in his congregation of five medical doctors, one emergency-room nurse and two nurses who are leads at the local vaccine clinic. Grace Mennonite still requires masks and distancing.

Still, Penner assumes some people will stay home. He speaks a lot about those people. Who are the ones left out?

His concern is that the most vulnerable people—kids, the immunocompromised, the medically fragile—are the ones staying away from church, while the double-vaccinated people who are least at risk can enjoy Sunday morning with others.

He knows of people who stay home every Sunday because medical factors prevent them from getting vaccinated or greatly increase their risk level. “I’m not okay with that,” Penner said of these people being left behind.

The congregation has considered the possibility of a service specifically for such people.

Penner takes a long view. “This will end,” he said, fully aware that the delta variant is likely to claim its toll in Manitoba before such an end. “In about 12 months, this is going to look very different for us,” he said. “How do we plant seeds” for healing and reconciliation?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.