In contemplating where our passions come from and why we do what we do, we often look to our childhoods. In my childhood, I was faced with several tensions, which formed me and led me to study history.

I grew up in Germany as a child of parents who arrived in Germany as Aussiedler (Germans who lived in Russia/Ukraine for about two centuries) only five years before my birth. One of these tensions was that I fully identified as being German, but I also found myself not completely fitting in.

Another tension I consistently struggled with as a child was learning about German history and the contrast to the history of some of my own ancestors. During both world wars, German settlers in Russia were seen as a threat, thought to be aligned with German political views and likely to join German efforts when given the opportunity. My grandparents and great grandparents struggled to survive deportation, dispossession, starvation, imprisonment or labour camps.

Growing up in Germany in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I found it difficult to wrestle with a German identity. School curricula included in depth material about the rise of Nazism, the fallout of the war, and lessons learned from our history. I frequently asked myself what I would have done, if I had been alive during this time.

As a result, from a young age, I wondered about the role of the individual in the context of extreme political movements, like fascism. How can and should individuals respond when our society or state turns to extremist ideologies?

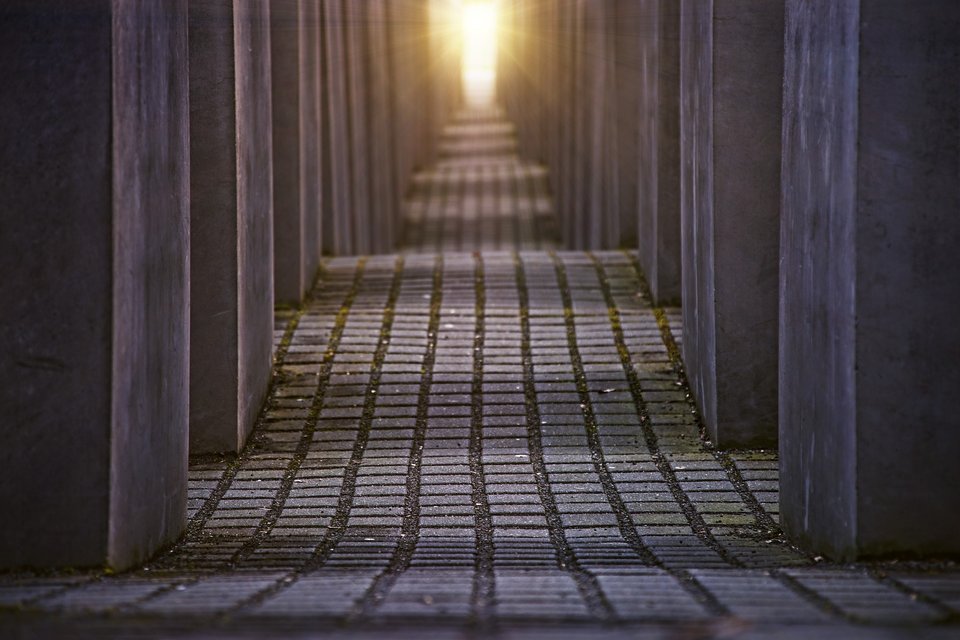

At the heart of my curiosity was the desire to understand how it was possible for so many people to be complicit in acts of genocide. This played a significant role in my studies as well. My search for answers led me to research the formation of Germany and the rise of nationalism in Europe. I learned that Germany committed its first genocide in German South West Africa (GSWA), now Namibia, between 1904-08. While it has not received a lot of attention over the last century, at that time, the German public was widely aware of the genocide of the Herero and Nama.

Average German nationals shared their opinions openly in colonial newspapers and encouraged harsher treatment of colonial subjects. National identity was wrapped up in competition with other powerful imperial nations and defined by exposing and extinguishing the other, the inferior. The public discourse relating to colonial subjects reflected overt racist, nationalist, and supremacist ideologies, which intensified over the following decades and created the environment that made the Third Reich possible.

The vast suffering, discrimination and deaths of the world wars pushed the global leaders of the time to urgently work together for lasting peace. Seeing humanity at its worst created a desire to make drastic changes. This is the context in which the United Nations was formed—in the aftermath of the Second World War. In 1945 the UN Charter and in 1948 the Universal Declaration of Human Rights outlined the recognition of dignity and equality for all members of the human family in order to achieve freedom, justice and peace.

I find the history of the 20th century astounding. The United Nations was formed as a reaction to war and violence, realizing that what mattered was the value of the individual. If the rights of the individual are not recognized, defended, and protected, then we—the human family—will not find peace. This was a massive shift, one that we are still trying to process.

I am a human rights advocate because I want to learn from our history and remind others that cultural and religious differences must not make us complicit in denying dignity and equality for all. I am a human rights activist because I believe it to be the responsibility of all of us to stand up against injustice, violence, and extremism.

Leona Lortie is the public engagement and advocacy coordinator for MCC’s Ottawa office. This post originally appeared on the MCC Ottawa Office Notebook.