“Pilate asked him, ‘So you are a king?’ Jesus answered, ‘You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.’ Pilate asked him, “What is truth?” After he had said this, he went out to the Jews again and told them, ‘I find no case against him’” (John 18:37-38, NRSV).

One way of looking at this passage is to see Pilate as the cynical Roman, refusing to believe in Jesus who had just made his righteous claim to be the king who spoke nothing but the truth. Because of his cynicism, Pilate does not see the truth, does not receive Jesus’ message, refuses salvation, and, according to an early church document called “The Acts of Pilate,” loses any chance at salvation.

This is a dire message for all people: Believe the truth about Jesus, who is the Truth, or lose any chance at salvation. Jesus is the Way, the Truth and the Life. There is no other way, truth or life.

Another way of looking at this passage asks the question, “How did anyone know what Jesus and Pilate discussed?” Is this not a “sacred fiction” written by John or another early Christian trying to make a point about Jesus, using Pilate as a character? This text is not about Pilate’s or anyone else’s salvation, but is about Jesus’ eternal kingship as opposed to any earthly, in this case Roman, rule.

This fit the need of the early church as it faced persecution by the Romans. Jesus’ pushback against Pilate showed them how to live: Don’t give in. Here is a message for today as we face the powers of government, capitalism and society: Don’t give in. Jesus is the original anti-government, anti-culture martyr. We need to follow his example.

Each of these responses to the passage from John 18 comes from a way of thinking that is complete in itself. Such ways of thinking are often called paradigms. From inside a paradigm certain truths are true beyond doubt. They make sense to those who live within this paradigm. People build their lives on these truths and are willing to live and die for them. Anyone who challenges these ideas is either ignorant, naïve, witless or purposely dense. In exasperation, those in the paradigm ask, “What is wrong with those people who don’t see things the way we see them?”

Understanding paradigms

These belief systems are not only religious or philosophical. The book that popularized the idea of the paradigm was The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn. Kuhn looked at how and when scientific ideas were upset and changed. How did the earth-centred idea of the universe get changed to a sun-centred idea, and then to a universe with no real centre, where every place is relative to other places?

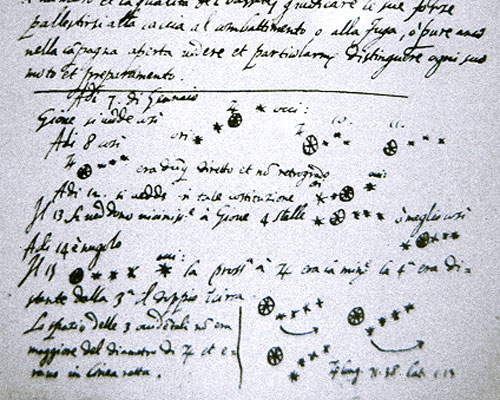

How did systems of belief, which led some to send others to their death for heretical beliefs in the wrong science, change? Galileo was silenced by the church because he had come to believe that the moons of Jupiter did not circle the earth, but Jupiter, contrary to the belief of his day that reasoned everything circled the earth. The earth was, after all, the home of humans who were made in God’s own image. As the highest point in the creation, everything else must be subordinate to humans and their home. This made complete sense to everyone.

According to Kuhn’s study of the history of science, the paradigm of a group of scientists in a specific area of science is not learned by memorizing rules and theories. Instead, newcomers to a discipline are given to repeat experiments whose outcome is already known, and are given problems which are already solved, to find again the known solutions. In this way, through practice, they learn the rules and theories.

In his book Worship and Evangelism in Pre-Christendom, Alan Krieder describes how new believers in the early church were brought into the paradigm of the church out of the paradigm of the Greco-Roman world in which they lived. Through a multi-year process of learning the mysteries of the faith, they slowly came to think from within the belief system. This system saw the story of God in relationship with humanity written in the Scriptures and the history of the world. Finally, they would be baptized on Easter eve and then be allowed into their first communion service/love feast, a celebration only baptized adherents to the Christian faith were invited to.

In her book A Mennonite Woman, Dawn Ruth Nelson notes that it was the community that taught faith in the Mennonite church for generations. Family, work, church and the community at large taught faith less than modelled it, and brought children up into it through practice. In both the early church and Nelson’s tight-knit Mennonite commu-nity, the faith made sense to everyone, just as scientific beliefs make sense to everyone in a scientific discipline.

When paradigms shift

The early Christian process of bringing new converts into the paradigm, the mind-set of the church, broke down when, after Constantine, culture became “Christians in Christendom.” No longer were Christians a minority with a different way of looking at life, but they became the majority living in a “Christian” culture.

The modern period of history—1400s to 1900s—believed that absolute truth could be found, clarified and articulated. This referred to philosophy, theology, sociology, psychology and all kinds of science. If human beings put their rational minds to work, they would discover truth such that everyone would come to believe it. Even theology became systematic.

As part of the Anabaptist stream, Mennonites are part of this modern belief system. Mennonites have believed that they can find the truth about God and humanity through a simple reading of Scripture and its application to life. We have believed we can find the truth, have found the truth, and that this truth can be easily appropriated by others. But the multiplicity of Mennonite groups should give us pause and raise a flag of humility to such a claim.

When it has become apparent that we disagree about something, we tend to separate, hurling claims of heresy or lack of Christian belief at those whom we are leaving or who are leaving us. We have not found the truth, none of us, no group, no individual.

What we have found instead are competing paradigms, each purporting to be the truth. This is a hard pill to swallow because, from inside a paradigm, the beliefs hold together, make sense, are applicable and hold emotional power over those who believe.

The potential collapse of a paradigm is fraught with fear, grief, depression and hopelessness. This potential can keep sane and rational people believing what others around them see as nonsense. We witness this in the Americas and Europe, where Christians are transitioning to a post-Christendom society.

The collapse of the modern paradigm

This year, in which we commemorate the centennial of the beginning of the First World War, can also been seen as a commemoration of the beginning of the end of modernity. That Christian nations could send out soldiers against each other, to kill each other in the millions, using the best of science in their military hardware, and based on the best of philosophy, has led philosophers and theologians to wonder about the whole project of finding truth, especially in Europe, since 1914.

Progress in North and South America through the 20th century kept modernity alive for the next half century, grinding to a sputtering end when the greatest Christian and most powerful nation on earth, the United States, was stopped by a little atheistic, Communist Chinese-backed nation in Southeast Asia: Vietnam.

During this same period, Einstein’s work on relativity shook the idea of there being a firm place to stand anywhere in the scientific world, and led philosophers to begin to question the idea of there being any objective truth.

Postmodern philosophers began to build systems of subjective truth. Much of what they developed looked relativistic to many, with no foundation for truth and no overarching story of human history.

In terms of faith, some people have developed highly personal belief systems based on what they have gathered from many sources. David Lyon, professor of sociology at Queens University in Kingston, Ont., calls this a “bricolage faith.” Like a collection of bric-a-brac, many have developed a faith and practice that is made up of bits of many philosophies and religions that work for them.

But this absolute subjectivity has not caught the imagination of everyone. Some have fled into quasi-modern belief systems, which give them assurance that what they believe is absolutely true and cannot, in the end, be satisfactorily challenged.

Fundamentalisms of many kinds are found in all the major religions. Choosing some point in history, theology or practice to draw their line in the sand, these groups build a wall around their beliefs and declare that anyone outside that wall is lost. In extreme cases, often called cults, people are cut off from all other ways of thinking and from people who think differently, in an effort to shelter the group’s paradigm from challenges. It is often the newest converts to a faith who are the most strident in their defence of it.

Others in modern culture have drifted into “infidelity”: a lack of belief in anything revealed by any god/God or held by any religion. Some of these continue to hold to reason and science as the places to find truth. Seeing that use of force and violence have yet to solve any human problems, they look to empathic acceptance of all people as the solution to humanity’s problems. It sometimes seems that the only people they cannot accept are fundamentalists.

When community-based faith breaks down

Dawn Ruth Nelson tells the story of her work in Northern Ireland during the “troubles” there. When the small intentional community of which she was a part broke down, she found that her acculturated faith could not carry her through the interreligious troubles in Ireland, nor help her to understand how her own Christian community could act so badly.

Many Christians find that they need new ways of thinking about faith and new disciplines to grow and strengthen their faith in the absence of the old commu-nity-based faith. Trying to live out their inherited faith paradigm in the different paradigms of human cultures, many are going through crises of faith. Nelson turned to contemplative Christianity to support her faith and work.

It has become clear that there is a need to have some truths upon which many can agree, and it has become clear that there are different ways of finding truth. These ways are not the old ways of an individual studying and developing truth, nor of an individual prophet receiving a revealed truth that all must obey.

Historians like Karen Armstrong have come to the conclusion that there is truth to be found by studying the wide experience of many people over time and space. In her book A History of God, Armstrong proposes that mystics past and present, Christian, Jewish, Muslim and beyond, have come to truths through lives of contemplation. These truths include:

- There is a god/God who can be approached, found and communicated with through contemplative prayer.

- This god/God works to change people from the inside out into empathic and love-driven workers for change in society.

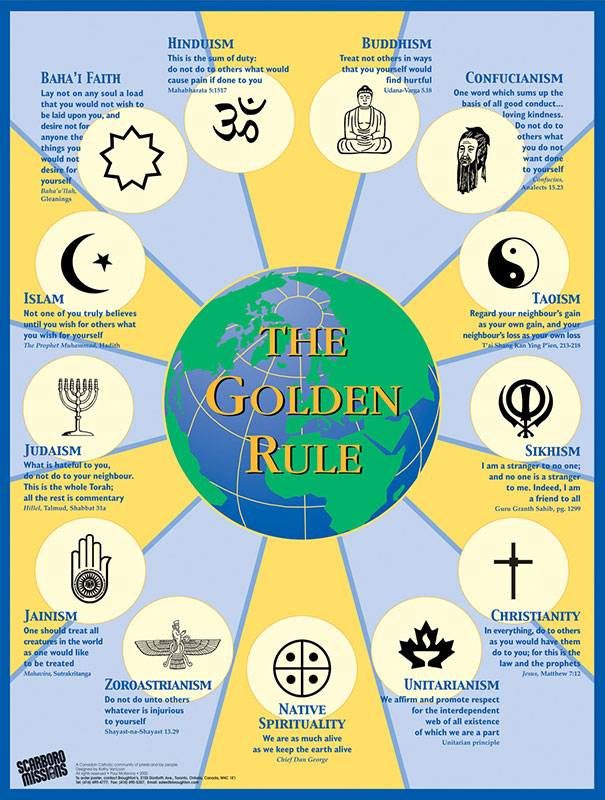

Because she finds this in many religions, she does not depend on outside influences like religious texts and practice, or hierarchies, to influence people. Instead, god/God works from the inside out to influence and change people no matter which religion nurtured and matured them. The Golden Rule—“Do to others what you want them to do to you” (Matthew 7:12)—is an example of this (see chart previous page). Jesus’ two great commandments—“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul. Love him with all your strength and with all your mind.’ And, ‘Love your neighbour as you love yourself’ ” (Luke 10:25-28)—is a Jewish/Christian summary of the same.

At the Mennonite Church Canada biennial assembly in Winnipeg this summer, Betty Pries called on participants to turn to contemplative life, surrendering to God all of their lives; abiding in Christ, allowing God to free them from their attachments to anything other than God; and to incarnate Christ in their lives. This directly parallels Armstrong’s findings from her study of the Abrahamic faiths.

Living truth

In his book Fractured Dance, Michael King looks at Hans-Georg Gadamer’s thinking about how to communicate when we disagree deeply, and how to find truth when we cannot rely on those in power to give it to us, nor can we depend solely on what has been revealed. All revelation is interpreted from within the paradigm of the interpreter, including the very act of translating a text from its original language.

Gadamer, a 20th-century Christian philosopher, believed that there had to be better ways to communicate in order to form communities. Instead of apologizing for our prejudices, Gadamer suggested that we offer them as a kind of gift to those with whom we disagree. We also receive their prejudices as a gift from them, given to help us grow in our understanding of the truth, since no one can ever have all the truth.

Separating into camps the way Mennonites and other groups have done over the centuries deprives those in other camps from the knowledge and feelings of the separating group, impoverishing all. Ideally, everyone in the human family would take part in this conversation, adding to the harmonies and dissonances, not finding a final truth, but all working towards current approximations of truth that future conversation partners in future generations would continue to develop. This is very similar to what indigenous people are asking of settler people in Canada: Learn to listen to each other even with deep differences.

Willard Metzger, executive director of MC Canada, spoke passionately at this summer’s assembly of a unity that was not based on finding “the truth.” With individuals, congregations and area churches in very different places on the topic of full inclusion of practising Christian homosexuals in the life of the church, Metzger wondered if unity were to be found in faithfully praying, worshipping and studying the Bible, even though we will not come to a corporate conclusion on the truth of the matter anytime soon, or perhaps not at all.

So what is truth? In the postmodern era, many have given up on finding absolute truth, but we still have truth to share with those around us:

- God is.

- God wants to be in relationship with us.

- God wants to grow us in the image of Jesus.

We can’t claim to base this on revelation from the Bible alone, even though we continue to treasure the Bible as a source of truth. We have to be able to share from our individual and corporate lives how we know this to be true. We have to live it.

–Posted Oct. 22, 2014

For reflection and group discussion, go to the discussion questions related to this article.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.