A gathering of strangers

The Christmas stories include an odd assortment of strangers. The guest list for the party that would eventually become the familiar nativity scene omitted all of the proper people: no clergy—you would have thought that the founder of a new religion could have been welcomed by the licensed prophets at least, if not the priests; no politicians—although they did try to crash the party; not even extended family—although social historians of the pe-riod insist that such an isolated birth, hidden away from everyone, was quite unlikely.

Nevertheless, the stories that have been handed down to us have not a word to say about aunties and grandparents and kindly neighbours. Nor about the mayor of Bethlehem or a representative from the local chamber of commerce in Jerusalem.

Instead, the guest lists that we do have possess an otherworldly air, as if the meaning of these stories does not depend on socially approved networks.

This is not to say that such family and community systems do not have the blessing of God. Did not Mary flee to see her cousin when her pregnancy called for womanly support? And surely the immediate and unusually close community in the early church, not to mention the deep friendships and mutual support surrounding the itinerant Jesus, give evidence of divine sanction on the loving ties that bind us together. Children do not grow well without a village network of some sort.

Yet the gathering of strangers that we celebrate each Christmas shows us something different but nevertheless just as essential. Ancient story after ancient story, whatever the culture, speak of a primeval, almost gravitational, pull between the earthly and the divine, between mere mortals and those who are clearly immortal. We humans were obviously not meant to live in material stuff alone—and, apparently, all those gods in the ancient stories were also not meant to live alone in splendid spiritual isolation.

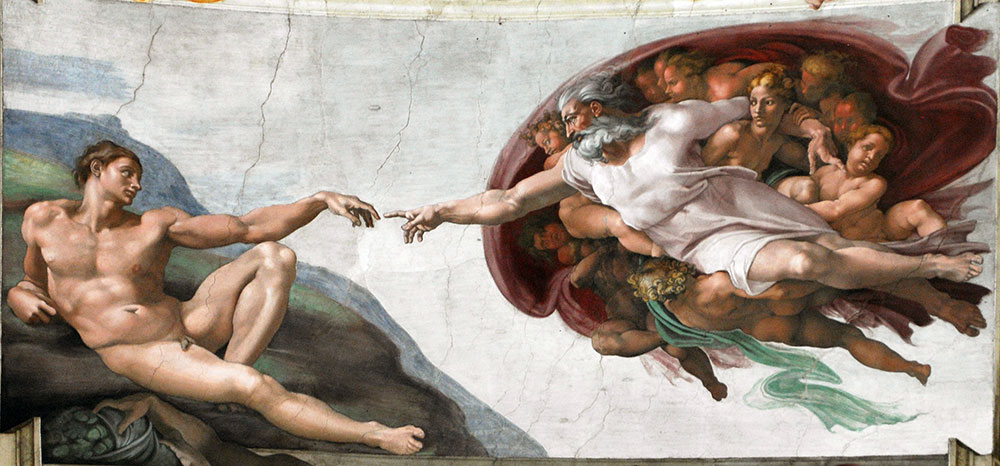

Likewise, Genesis records a divine desire—“Let us make man in our image”—followed by profound conversations in a garden. There is always traffic between heaven and earth. That Jesus is thus a union of divine and mortal signals an ancient truth that underlies all worship: from creation onward, in love’s deep sacrifice, God’s outstretched eternal finger touches the outstretched finger of the mortal Adam.

At such mysterious meetings otherness ceases to be, and the guest list includes strangers who are no longer strange, who belong. So we have the angels hovering over the archetypal family. Did the anxious father, his heart still beating in triple-time, hear the whoosh of angel wings? Maybe. Joseph had already conversed with angels and would do so again. I suspect the exhausted mother, so very close to miracle already, might have heard them or simply known that angels had to be there. Representatives of God, of course, they had to be there.

So did the shepherds. Their boots likely still carried tufts of grass and their clothing a smell of wet wool. However we try to romanticize shepherds—and poetry since the early Greeks, as soon as there were cities of any kind, has done its best to separate shepherds from their sheep and turn them into symbolic poets or pastors, and make them stand for innocent simplicity or uncorrupted erotic love—they still retain, and will forever retain, a whiff of the disreputable, a whiff of manure. Of course, they were the ones who saw the angels. Who else was close enough to earth to be able to hear heavenly music? Who else had time and space for unearthly intrusions?

Evidently the Wise Men did. The Magi, gentile astrologers likely, were sufficiently detached from the fuss of daily-ness to be able to read the stars, and then to follow wherever starlight led them. It is disturbing to realize that in current literature, typically, the sage only appears in the kind of stories we dismiss as children’s fantasy. The real world doesn’t have any Dumbledore or Merlin, just a dress-up Santa Claus commercialized past all recognition of old stories of giving. But, as the Christmas stories inform us, the real world could do with more contemplative thinkers, the strange ones who see straight through the transient busyness that so occupies us, to the detriment of our souls.

Yet, in defiance of the relentless materialism of our time, perhaps not so different from Jesus’ time, the nativity scene, with its gathering of otherworldly strangers, still begets more Christmas stories of strangers welcomed, of eyes opened suddenly to see the angels who are indeed always with us.

Exile and return

The least favourite part of the gospel Christmas narratives is the gratuitous cruelty of Herod and his obedient soldiers. Well, perhaps not all of that part. There’s something compelling and exciting about the Wise Men’s adept escape from Bethlehem without offering Herod the details he wants.

Every good story needs a villain and the escape of the innocent, maybe even a clever outwitting of the villain. Such story development quickens the breath of the hearer: Will the beautiful newborn baby get away? Will the travellers make it safely back home after their long pilgrimage? The intervention of angels adds the miraculous touch that signifies the status of this baby as the hope of the world.

It takes nothing away from the Christian story to notice that such narrow escapes of the unlikely babe of hope occur in other traditions as well. These similarities in the stories underline our sure faith that of such is the fabric of the world. It must always be thus. The hope of goodness, the hope for redemption, is slender, fragile, yet astonishingly safe and enduring. This baby will live, yes, and a thousand Herods will go the way of all flesh. What matters an unscheduled trip into Egypt? So many heroes have entered the world in surprising ways and then disappeared into exile, only to return at the crucial moment to save their people.

What the gospel narratives offer us, however, is not nearly so sanguine or satisfying. In reality, evil seldom rages harmlessly on a narrow stage. What many hero stories fail to show is the cost of redemption for all the bit players in the story, all those ordinary people who attempt to get on with life, often oblivious to the grand narratives in the making.

The innocent do not, after all, escape. It is almost intolerable for us to imagine the senseless death of babies and toddlers, all for Herod’s blind and stupid drive to maintain power in the face of the mysterious force of love, which shuns the tools and trappings of power.

Thus, despite the innocence and almost naïveté of a simple birth watched over by angels, the Christmas story is full of the tension that will become a central theme of Jesus’ ministry: his repeated repudiation of the violence and oppression of empire. For the drive to power inevitably makes grieving, empty-armed mothers.

The figurative image of Rachel weeping for her children stands in blunt contrast to Jesus, the man, with children in his lap and widows among his followers. Imagining the horror of all those weeping mothers in Bethlehem and Judea makes us face the consequences of our ways, whether those are openly militaristic or merely a typical grasping for advancement at the cost of others. Christmas is thus a story about consequences. Small wonder that we hasten by the weeping Rachel and look eagerly to Egypt where the exiled hero awaits return.

Yet even the story of the flight into Egypt has its dark underside, for it suggests that we do not always recognize a Saviour when he comes. This, too, is a common theme in the world of story. Those who would do their people good seem to need a time apart in which to let longing grow, vision sharpen and wisdom increase.

Moses needed at least 40 years away from his fancy palace beginnings. And if it seems harsh to imagine Mary and Joseph far from their home in Egypt—the land of exile (remember the Israelite slaves)—then think of what it means to be exiled from the knowledge of and presence with God.

It is a part of the human story to experience separation before a return brings hope. To imagine Jesus as homesick for God the Father sharpens our own sense of loss, for we are all aware, sometimes more keenly than others, that we are far from what we instinctively long for. The image of exile speaks to everyone. Whatever at-home-ness we sometimes achieve remains fragile at best, easily shattered by accident, loss, disillusionment. That is why the story of the return of the hero speaks so deeply to us.

Christmas, of all times, is so often about returning and not being able to return, about being at home and not being at home. About hope.

A giving of gifts

As baby shower gifts go, gold, frankincense and myrrh are on the unusual side, if not downright quixotic. Only men utterly caught up in their astronomy, philosophy, astrology and religion could offer the poor parents of a newborn something so far beside the point. Surely more of whatever women used then to diaper their infants, or even some more swaddling cloths, would have been more suitable and more necessary.

Yet in my head, I hear the cry of old King Lear in Shakespeare’s play, “Oh, reason not the need!” Are gifts supposed to provide the necessary? Lear knew that his many attending soldiers were not necessary, not in any reasonable sense. But their presence testified to his identity. Without them, he was something less than king—stripped, half-naked, vulnerable. Shakespeare does not usually minister to our hearts at Christmas, but in this case, this old king names something we should know about gifts.

While gifts sometimes do fill a material need—the poverty-stricken student accepts with gratitude a food voucher or a decent blanket—at their truest, gifts are part of the self that is offered to another self. Out of the exchange arises a new dependency, a new identity, however briefly and partially understood. What I give to you expresses something of myself, both of what I imagine you to be and of what I am.

The old story, “A Gift of the Magi” by O. Henry, illustrates this well. A young woman sells her long beautiful hair as the only way to get enough money to buy a gold chain for her husband’s gold watch, his one valuable possession, and his one testament to better days and his noble birth. Meanwhile, he has sold that gold watch to buy his wife expensive combs for the beautiful hair she no longer has. The gifts are now quite unnecessary in any practical sense—if they ever were. What moves us deeply in this story is the dramatic giving of self: Both gave what was part of who they were in order to enhance what the other was, and each thus demonstrated the love and sacrificial willingness to give that which was also a part of each.

Just so, the original Magi gave to the baby Jesus what identified them, and thus, perhaps unknowingly, testified to the identity of that baby:

• Gold is the purest and most valuable of metals. It is the sign of kings. Not only that, but its beauty and its endurance through all fire have given it divine status both in biblical lore and in other stories. It is immortal and thus belongs to God.

Its medieval symbol was a circle with a point in the middle. Circles are symbols of perfection. To think of Christ as the still point in the centre of perfection magnifies the Magi’s gift into the perfect acknowledgement of the self that he is.

• Frankincense and myrrh were both resins from which expensive incense could be made. Frankincense was sometimes burned as part of a sacrifice, and myrrh was also used for embalming. That both are grouped with gold indicates their value and their cost.

Thus, all three gifts signify both the wealth of the Magi and the kingly identity of the baby. Such gifts are not necessary, practically speaking. They are, however, an offering of the very self of the Magi for the establishment of the very self of the baby who will become the crucified Lord.

Such gifts are not free. Indeed, I wonder if gifts are ever free, because the very nature of a gift requires something of the giver—thought, time, cost, imagination—and something of the recipient. In order to receive a gift, I must acknowledge dependency. I must acknowledge that my life, my self, my goods, will somehow be enriched by this gift that I now take. The gift retains something of the giver, something of the giver’s very self, and thus it demands that I respond, in some way. I am not free to throw it away, for thereby I throw away something of the giver, which he or she has committed to me. At the very least, I have to respond, however tentatively, to this embodiment of what the giver sees in me.

On the one hand, this understanding of giving magnifies immeasurably the gift that is the baby Jesus. To think that God embodied himself, gave of his self, as testament to what God sees in us, is to take our breath away. On the other hand, such a vision of gifts shames us for the me-chanical piling up of stuff that constitutes our usual Christmas giving. To offer more stuff in response to a cultural mandate to shop until we drop, and in response to lists of people and lists of requests, can be a diminishment. Is this all of my self that I am prepared to give? Is this what I think of you for whom I have hastily grabbed whatever was nearest on the shelf?

We all function within our cultural spheres, and accept, more or less unthinkingly, the definitions that are current. Gifts are not usually defined as lofty exchanges of the self. So be it. However, in the quiet of the morning after, can we contemplate the rich symbolism of the giving of gifts with which we remember and re-enact the young child’s hands reaching out to accept the gold, frankincense and myrrh? l

Edna Alison Froese, a self-employed academic editor, wrote these Christmas mysteries and presented them to her Sunday school class at Nutana Park Mennonite Church, Saskatoon, in 2007.

—Posted Dec. 10, 2014

For reflection and group discussion, go to the discussion questions related to this article.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.