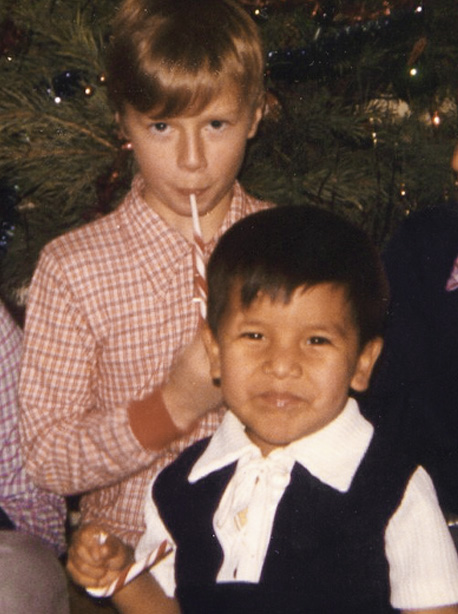

Mark: Our parents were extremely loving, amazing people. I remember a time I asked Mom why they had adopted kids. My mom’s response was so simple: because there was a need.

I remember when we were still living on the farm, becoming very aware that Kelly and my other brothers’ ancestors had been on the land for thousands of years, [while] my genetic ancestors came in the late 1800s. It was there, written in the land. On part of our pasture, there were vestiges of a tipi ring. I found a hammer head. Not far away there was a buffalo rock where bison had worn it away.

Kelly: I was 13 months when I was adopted. I don’t recall being an unhappy kid. I was a relatively easygoing kid. Even though I knew I was different, and I do remember my parents trying to convey this, I didn’t have the connection to the land or the people. That didn’t come until later.

Mark: Our parents took us to White Bear First Nations [near Carlyle, Saskatchewan] because there was a powwow there, and they were trying to provide Kelly a connection to that. I think they felt they weren’t welcome, so they only tried it the once.

When I was 16, and Kelly was 10, we moved [from a farm] into the city of Weyburn. It was a pretty white town. I thought Kelly and our brothers didn’t experience a lot of racism, but you’ve set me straight since then. You’re the one followed by a security guard in a 7-Eleven, despite the fact that you trained as a police officer.

Kelly: It happened last week.

[When we moved to Weyburn], I was told I was different—people telling me I was a typical Indian. In Weyburn, I was that one guy—you’re “those people.”

In my twenties, I started to make the connections [with the land and my birth family]. The last couple of decades, I’ve had an opportunity to participate in inner-city outreach, men’s ministries, and to get a feel for people around me, and I’ve started to make connections with land.

I knew I had a younger sister…. Then my younger brother reached out and got information to Mom and Dad, who passed it on to me. [I found out] I had a younger brother and four younger sisters as well as my birth mother. I met them all in that year or so.

They didn’t practice traditions, speak the language. They were just people like any other people. Even meeting the birth family, there wasn’t a connection to the people, reclaiming my identity. It was a little step. I didn’t make those connections until I started going to church in the early 2000s.

Mark: People like me—white men—go through the world not thinking about being white men. The closest I got was spending a month in Saudi Arabia, but they were happy to see me there, even though I was the minority.

Kelly: Being aware of how different you are when you apply for a job, go to the store—we are literally looked down on by everyone, even other people of colour. Not being able to deal with that as a kid sends people in a direction that’s terrible. It’s a rare place I can go and just feel normal.

One time I went to get gas, and I encountered three or four guys who are Indigenous, and something came up about the government, and we all shared a big laugh. It was one of the few times in my life that I felt I belonged.

It felt good and sad. I have to have the perfect timing to feel that.

When it comes to the Scoop, the [experience] I had was not terrible in the ways a lot of people think. A lot of Indigenous people have far worse experiences. But I can’t imagine how anybody would have a one-year-old child just removed.

I got picked on, beaten up, treated differently by adults, teachers, everybody. I turned into a person who didn’t have a culture, language. I had a lot of needs I didn’t know how to express in a healthy way.

There’s trauma. That’s a part of me I will have to manage for the rest of my life. It shows up in ways that isn’t always expected.

But the Sixties Scoop didn’t entirely work, because I’m actively reclaiming my identity. Learning language will take a while. Making connections with White Bear First Nations will likely take the rest of my life. I have four children and two grandchildren—I can pass on a legacy of reconnecting myself. There’s been a lot of good [in my life]. Not everything has been the tragedy people think it would be. I don’t have to abandon the family I have now. I have to dig for different ways of looking at family.

One of the unique things of my path—coming to the church and finding Jesus in my life—is probably the one thing that’s washed me clean in ways that had to happen for me to be on the path, and then to be able to look at how my life has been and be thankful. There are things I can’t change, but I can move forward in a good way and leave a legacy my children and grandchildren will look at and say: here’s a guy who made a change in his life. That’s what drives me. But not everybody can do that.

Mark: Our parents were amazing people, and it’s bothered me sometimes when I’ve told people I have Indigenous brothers. The way I think about it is this: way back in time, Ptolemy came up with a way to study the solar system, and he was wrong. He was still a brilliant person, and we had to go through that era to get to Galileo.

Individual people can be involved in an awful system and still be good people. It’s hard to transcend the limitations of our culture. The Jesuit priests believed what they were doing was good, and they sacrificed their lives.

From what I heard, Kelly, your birth mom was in a bad place. Not herfault—the system created this situation, but within that system there were people like our parents who were trying to help. It’s a complicated thing. The Sixties Scoop was awful, but there were people trying to do good within that.

Kelly: The way I view the Sixties Scoop class-action suit is that my life was worth $25,000. Plus, I had to agree to the terms that I may never partake in another class action. The government is still doing things in the best interest of the government. I don’t expect 90 per cent of Canada to go back where they came from, and we get our land back. That is so far from reconciliation.

I say: if you all came with the intentions of collaboration instead of conquest, we wouldn’t be in this situation.

How can we move ahead together? That’s the goal: we need to be a we. I can’t be a second-class citizen and expect reconciliation will move forward. It will be at a glacial pace— that’s how these things happen.

In discussion with Indigenous Christians, the biggest thing they say about being an ally moving forward with reconciliation [is that] it will take real empathy and listening, taking advice on how to move forward.

Whether it is about the Sixties Scoop or reconciliation, one thing I think people who have been harmed want is to be heard, to know that they matter.

Until we can look at each other like people—on both sides—we can’t move forward. I have extended family on my birth side who say the same things in reverse. Some are not ready to receive, to partake in reconciliation. It may take a generation to wash that away. You have to have a heart, courage, willing- ness to listen with an open heart and learn some new things.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.