This year the Mennonite Brethren Church is celebrating its 150th anniversary with a week-long celebration in B.C. in July. What have the MBs contributed to the wider Mennonite community during the past century-and-a-half? What has been its relationship to Mennonite Church Canada, or to the General Conference Mennonite Church, which also began in 1860?

Desire for renewal leads to split

The MB Church began in the midst of significant change among Mennonites in Russia. Lutheran pietism had influenced Mennonite communities there for a number of decades, and had provided a leaven for renewal.

It was in 1860 that some members in the Gnadenfeld Mennonite congregation in the Molotschna settlement petitioned their leaders to meet separately for commu-nion. These members did not want to celebrate communion with those who had not experienced personal Pietist renewal and conversion. When the leadership refused to grant their wish, these members met separately, celebrated their own communion and founded the Mennonite Brethren Church.

In the Chortitza settlement a similar group formed under the influence of German Baptists. Soon these two groups in the Chortitza and Molotschna settlements merged as the Mennonite Brethren Church. Since the Baptists practised immersion baptism, the church adopted immersion as its distinctive practice.

The reason for forming the MB Church was the desire by those renewed through the influence of both Lutheran and Baptist pietism to form a church that would include only like-minded people. In contrast, the other Mennonite churches accepted the new pietist influences as well as the historic Mennonite practices and pieties. The MB’s separatist stance and its active proselytizing among Mennonite churches created tensions with those churches.

After a while, some MBs became unhappy with the gulf that had developed between their church and the Mennonite church, and they spearheaded the formation of the Allianz Mennonite Church. This church tried to be a bridge between the two, permitting both pouring and immersion baptism, and allowing for more diverse religious pieties.

At first, the new MB Church also drew Russian and Ukrainian neighbours into membership. When the church tried to incorporate as a legal entity, the Russian government informed it that if the church included Russians and Ukrainians, it would not come under the provisions of the Mennonite Privilegium of 1800, according to which Mennonites were exempt from military service and could have their own schools. In order to not lose those privileges, the MB Church divided, with the Russian/Ukrainian members forming the Russian Baptist Church. Thus, the start of the MB Church contributed directly to the formation of Russian Baptists.

The Mennonite Brethren made significant contributions to the Mennonite community in Russia. They were the first to accept four-part choral singing into their church services.

Although the MB Church did not pio-neer Mennonite schools of higher learning, soon many of its members gravitated to higher education and served as leaders in those schools. This emphasis on education carried over into publishing and writing. An example of this activity was the publication in 1912 of Peter M. Friesen’s The Mennonite Brotherhood in Russia, 1789-1910, still one of the best resources for understanding the Mennonite experience in Russia.

Inter-church tensions follow MBs to North America

The Mennonite migration to North America in the 1870s had far-reaching significance for the future of the MB Church and for its relationship to other Mennonite churches in North America. Since the MB Church was largely shaped by Pietism, and the General Conference Mennonite Church by American revivalism, one could have expected the two to make common cause. After all, many of their emphases on renewal, conversion, missions, education and newer forms of worship were similar. But the two groups didn’t join, and that shaped both of their subsequent histories.

What happened, instead, was that many of the other Mennonite immigrants who came from various churches in Russia joined the General Conference. Thus, the tensions that had existed between the Mennonite Brethren and the other Mennonite churches in Russia were now transferred to the relationship between the MB and the General Conference churches. This was a tension that need not have happened, but it did.

In the U.S., with evangelism as its primary focus, and because of easy access in the German language, the MB Church continued to target other Mennonite churches. This created tensions. When the MB conference, centred in Kansas, sent “missioners” to the Winkler area of southern Manitoba in the 1880s, who formed the first MB church in Canada, this set up further tensions with Mennonite churches in the area.

Shortly after the formation of the MB church in Burwalde, Man., American MBs moved north to Saskatchewan. In 1913, these immigrants formed the Herbert Bible School, the first Mennonite Bible school in Canada.

In 1906, the MB conference founded the first Mennonite congregation in Winnipeg. Since at the time there were few Mennonites living in Manitoba’s capital, the focus of the city mission was primarily German Lutherans.

‘Second wave’ of immigrants bring denominational loyalties to Canada

The immigration of 20,000 Mennonites to Canada in the 1920s, about a third of which were Mennonite Brethren, initially promised to change the dynamic between the MB and other Mennonite churches. The immigration itself required cooperation between Mennonite groups in both Canada and Russia. In Russia, the emigration movement was led by B. B. Janz and C.F. Klassen, two MBs. In Canada, it was led by David Toews, chair of the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization and moderator of the Conference of Mennonites in Canada, now part of MC Canada.

Upon immigration, members of the Mennonite and MB groups worshipped together in many locations. In Ontario, the MB churches formed a conference with similar emphases to those of the Allianz Mennonite Church in Russia. For a short while it looked like the trauma and difficulties of immigration would result in healing the divide within the Mennonite community.

Then, however, institutional and denominational loyalties rose to the fore. Each of the joint worship centres separated, and in each community two denominational churches formed. As the price for membership in the North American MB conference, the Ontario MB conference was required to abandon its Allianz character and rebaptize members who had been accepted without immersion baptism.

Other attempts at working together also failed. For example, the MBs founded three schools in Manitoba: one in Winkler (1925), another in Steinbach (1930s), and a third—Mennonite Brethren Bible College—in Winnipeg (1944). In each case, overtures were made by other Mennonite groups to make these schools inter-Mennonite. In each case, the MB groups rejected the overtures.

Areas of cooperation include music, MCC, CO service

There were, however, also areas of cooperation.

In music, for example, K. H. Neufeld immigrated to Winkler from the Soviet Union in the 1920s and quickly became a conductor of choirs and orchestras in both MB and Mennonite churches. Franz C. Thiessen made a similar contribution in Saskatchewan, and later in Winnipeg and B.C.

During World War II, the Mennonite Brethren, Conference of Mennonites in Canada, and the Swiss Mennonite conferences in Ontario together proposed to the federal government alternative service as their form of conscientious objector service.

The change of worship language from German to English in the 1950s and ’60s created a new set of relationships between the MBs and other Mennonites. For one, this change allowed the focus of MB evangelism to expand to the whole society. Thus, inter-Mennonite cooperation no longer posed the same threat to the potential for MB growth as it did earlier, when the Mennonite community formed the primary base for MB outreach. Subsequently, MBs were involved in the founding of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Canada in the 1960s, and in the establishment of Columbia Bible College in B.C. in the early 1970s. This spirit of cooperation continued in the formation of Canadian Mennonite University (CMU) in Winnipeg in the 1990s.

The language change allowed MBs to accept many of the emphases of the Canadian evangelical movement. MB pietism was transformed into Evangelicalism. For some MBs, the influence of Evangelicalism meant stronger ties to evangelical groups, and a decrease in the emphasis on peace, service and other historic Mennonite emphases.

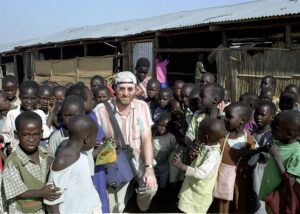

Other MBs were influenced by the renewal impulses of the “Anabaptist Vision,” associated with the name of Harold S. Bender. Many within this orientation became strong promoters of peace and justice issues, and supported inter-Mennonite organizations like MCC. MBs also played significant roles in founding and supporting various inter-Mennonite service organizations like the Canadian Foodgrains Bank (see “Briefly noted” below) and the Canadian branch of Mennonite Economic Development Associates.

The present situation

The relationship between the Mennonite Brethren churches and other Mennonite churches has changed significantly during the past 150 years. From the early years—when Mennonite churches saw the MBs as a threat and the MBs saw the others as not truly spiritual—the two sides have moved to a relationship where, even though they are somewhat different, they can accept and learn from each other.

Recently, an MB leader commented that he felt the MBs’ contribution to the larger Mennonite community was an insistence on a strong, clear, personal commitment to Christ. What he thought the MB Church could learn from MC Canada was the importance of service and peace. This attitude of seeing each other’s strengths as complementary seems to be the prevailing mood today.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.