What do Mennonites and former gang members have in common? “Not much,” one might be tempted to reply. But at a recent Saskatoon conference they sat side-by-side learning about gang intervention and prevention, and the way back to a healthy life.

Presented by Str8 Up, an agency helping young men and women liberate themselves from gangs and a criminal lifestyle, and with Mennonite Central Committee Saskatchewan as one of the sponsors, “10,000 Healing Steps: Resilience and community” attracted around 500 people from across the province on Feb. 5 and 6, many from first nations communities. An additional 400 high school students participated in a youth session featuring former gang members telling their stories.

Stacy, a former gang member, told his story of growing up in a violent household. When his father died, he said he felt abandoned and without a role model. Noticing that people admired young men who had served time in jail, he said he wanted to be like those men, so he started getting into trouble with the law.

Rodney, another former gang member, said he was abused as a young boy and spoke of how this impacted his life. “I’ve forgiven myself for what I’ve done,” he said. “The hardest thing is to forget what was done to me.”

Robert Henry, a Ph.D. student of native studies at the University of Saskatchewan, said those who join gangs are among the most marginalized people in society, live in extreme poverty and are typically members of ethnic minorities. They fall into the gang lifestyle not so much by choice, but by a lack of choice, he said.

Healing begins with relationships and community. While policing and corrections help control gangs, they should be a last resort, according to Mark Totten, professor of criminal justice at the Humber Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning in Toronto. Instead, communities should work at prevention, he recommended.

“We can identify high-risk kids by age 6,” said Totten. Using schools or other facilities as a hub for delivering a whole range of services—such as breakfast programs, clothing cupboards and parenting classes—communities can help high-risk families feel supported, he said. Children, in turn, will be less likely to adopt a criminal lifestyle.

Although not specifically gang-related, the Micah Mission, an agency affiliated with Mennonite Church Saskatchewan, offers services to offenders and ex-offenders through the Person to Person program, Circles of Support and Accountability, and Community Chaplaincy. Coordinator David Feick, along with board member and volunteer Eric Olfert, presented the mission’s work during a workshop. Feick said that when people get to know these men, they discover “they are not that much different than we are.” Through friendship with volunteers, he said they feel supported and are less likely to re-offend.

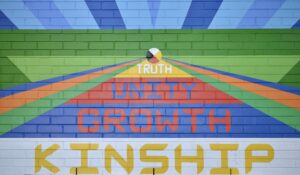

While the work of the Micah Mission and Str8 Up is necessary, it may not solve the problem. As Father Gregory Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries, Los Angeles, explained, “If you want to change the world, you have to change the metaphor. Gangs are not primarily a crime issue; they are a community health issue. Intervention and prevention are necessary, but still don’t get at the community health issue.”

As the conference title suggests, however, the work these agencies do may be the first of many steps toward healthy, resilient communities. So what do Mennonites and former gang members have in common? Perhaps, among other things, they share the goal of healthy lives and healthy communities.

–Posted March 8, 2014

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.