Update: In October 2020, Mennonite Church Eastern Canada announced the termination of the ministerial credentials of John D. Rempel, on the basis of ministerial sexual misconduct. To learn more, see ‘Credentials terminated for theologian-academic-pastor.’

The Book of Acts is the record of what happened to Jesus’ followers when their universe exploded, when the Holy Spirit, the embracing presence of God, came upon them. Their world was turned upside down. Jesus’ friends were baffled by the wildness of God’s new presence: The Spirit kept going ahead of them; they couldn’t hold the Spirit fast.

The story, as told in Acts 10 and 11, has all these traits: upside down, wild, elusive. In fact, the opening scene of the drama features not an insider, but an outsider, Cornelius. The writer tells us that he feared God. God-fearers were pagans who had come to believe in the God of Israel and abide by Jewish law. But the Apostle Peter, the other actor in this narrative, was convinced that his part in Jesus’ mission was exclusively to bring the Messiah to his own people, the Jews.

Cornelius and Peter lived in separate worlds, like Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada. Left to their own devices, they would have stayed separate. But God intrudes on both of them by means of a vision—a moment in which we see and hear something about God that can’t be argued away.

Cornelius is terrified when he hears an angel’s voice. The angel commands him to send for a man from the faraway town of Joppa. This man will be God’s answer to Cornelius’s prayer.

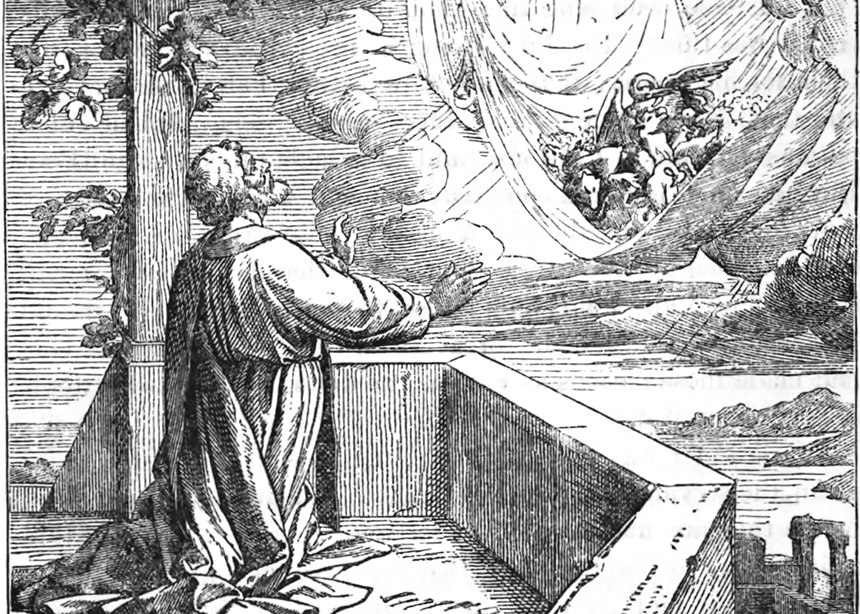

Meanwhile, Peter, who doesn’t know that yet, retreats to a quiet place in his house to pray. Suddenly he falls into a trance and sees something like a sheet lowered from heaven filled with unclean animals. He is told to eat them! Peter is revolted by this blatant violation of Jewish dietary law.

Before he has time to make sense out of the vision, there is a knock on his door. Men sent by this strange seeker, Cornelius, prevail upon Peter to go with them. It is only in the course of their journey that Peter begins to grasp the meaning of his trance. His opening words to Cornelius’s household show this: “I truly understand that God shows no partiality.” He is beginning to see that his presence in a Gentile home is not a violation of God’s intent but a fulfilment of it.

When Cornelius and Peter meet, it’s hard to tell who is more shocked. But both of them are convinced that God is behind this encounter. Meanwhile, Cornelius’s whole household has assembled. Peter’s first words astonish his hearers: “I truly understand that God shows no partiality but in every nation anyone who fears God and does what is right is acceptable to him.”

As Peter lays out his novel claim, the Holy Spirit falls on everyone in the room who believes; these outsiders to the covenant begin speaking in tongues just as the messianic Jews had done on the Day of Pentecost! When he gains his composure, Peter cries out, “How can we withhold baptism?”

The next episode in this uncanny tale

Peter retells his astonishing encounter to the messianic Jews in Jerusalem. First of all, they scold him for breaking bread with outsiders to the covenant. In response, Peter recites the highlights of his encounter with Cornelius: the vision with the sheet holding unclean creatures, the ominous knock on the door, the journey to Caesarea, and the overwhelming reception he received from his hosts.

He then asks his interrogators a rhetorical question: “If then God gave them the same gift that he gave us when we first believed in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could hinder God?”

At first, the Jerusalemites are shocked into silence. But soon they, too, praise God.

Now that we’ve heard this story, what do we do with it? How can we apply it to our lives today?

First of all, this is a tale of two conversions.

The obvious one is that of Cornelius. We are let in on the secret friendship the Holy Spirit has entered into with him. But Peter also needs to be converted, because he can’t imagine that God has opened the covenant God made with Israel to all people.

The revolution in Peter’s ministry happens when he learns that Cornelius is not an outsider to whom he can be indifferent, but someone in whom God’s Spirit is at work. He learns that nobody whom God has created is unclean or beyond the call of God’s grace. True evangelism happens when both the seeker and the witness are changed by meeting each other. The church is not “them” becoming more like “us,” but all of us becoming more like Christ.

As I prepared this sermon, I heard Cornelius and Peter’s adventures as if for the first time. Their excitement was contagious: God is at home in the hearts of everyone who will let him in. Witnessing to Christ is not a matter of trying to talk someone into something. Rather, it is being ready for a moment of truth when we put a name to the stirrings in someone’s heart.

From contagious excitement to troubling issues

But the words of the church’s witness often seem hollow. Too much talk about God trivializes God’s reality. How on earth can we say something new about Jesus that people haven’t heard a hundred times in church or on religious radio?

In our society, religion is advertised like cars and appliances. Those of us who have grown up in the church know its—and our—lapses into self-righteousness and hypocrisy. We squirm at calls for evangelism that seem triumphalistic and condescending. We feel that the least we can do in reclaiming some level of integrity is to keep our mouths shut. There are times, surely, when the truest witness is silence.

Mennonites are good at knowing that our witness to the gospel begins with how we live, before we talk. In fact, most of our confession of Christ consists of patient and persistent love of friend and enemy.

But then there are times when the Spirit prepares someone in our life to hear in words the reason for the hope that is in us—someone like Cornelius. If we remain sensitive to the stirrings of the Spirit, we will know those times. If we remain silent, don’t we leave the impression that we’re good enough in how we live that our way of living will always point to God? The liberating message of the New Testament is not that we love others because we’re good, but because we’re loved.

Second, attempts to persuade someone of my truth seem disrespectful to people of another religion or of no religion, people with whom we work and live every day, or members of our family. Shouldn’t we respect people different from ourselves and not suspect them until they become like us?

This is the really tough question. Here I find a tension between two truths that can’t be let go of. God’s Spirit stirs in all people, so we should look for stirrings of the Spirit in people of other religions, in their prayers and in their love of justice and mercy. Only God is their—and our—final judge. Our role is that of witnesses. If, like Peter and Cornelius, the Holy Spirit has shown us Christ as a living presence in our lives, we cannot help but reflect that in how we live and what we say out of gratitude for the gift of Christ.

Holding this tension in life giving ways

I have seen the Spirit call a Jew to Jesus. When I was the minister of a Mennonite congregation in New York City, we had a member named David. He once told me his faith story. He had been a secular Jew with no interest in religion. One day, as he was in the hospital recuperating from a cancer operation, he saw Jesus standing at the foot of his bed, radiating love and saying to him, “I want you to follow me.”

David told me that the call was irresistible. At the same time, coming to faith in Christ did not lead him to abandon Judaism or to doubt God’s covenant with the Jews. Yet, when he encountered people unmistakably looking for something they had not yet found, he risked a witness to Jesus as Messiah.

I have read stories of Islamic believers having a similar unbidden mystical encounter with Christ.

If we hold on to this tension, we will honour the faith of others while being a sign that Christ is alive—by our deeds, our words and our silences—to those who seek him.

The more urgent concern of the church’s mission, however, is not people with another faith, but people with no faith, no community. In our secular society, the majority of people make no religious claims. When we see them love mercy and do justice, let us make common cause with them. When we see them broken by injustice, alone in the world, or seduced by things that cannot satisfy, let us point them beyond themselves—and ourselves—to the One in whom all things hold together. It is not ourselves we proclaim, but the One whom death could not hold.

I long to share the excitement of Peter and Cornelius when God turned their world upside down by leading them to others who were waiting for someone to tell them about God.

There are no pet formulas, no clever tactics, to being a witness. It calls for a way of living that listens for the promptings of the Spirit, either directly or through others. As we listen for the Spirit, let us remember that there are times for deeds, times for silence, times for words. Let us remember that there are many Corneliuses, or Cornelias, in the world, women and men in whom the Spirit of God is at work, waiting for some Peter, or Petra, to be a sign of Christ.

How will we respond the next time the Spirit says to us what she said to Peter: “Look, these people are searching for you. Now go down and go with them, for I have sent them.”

Will we turn back in fear or will we take the risk?

John D. Rempel is a Senior Fellow at the Toronto Mennonite Theological Centre.

For discussion

1. Have you ever had an angel of God speak to you, or heard someone else describe such an experience? Why might that event be disorienting? Does an experience with the Holy Spirit ordinarily lead to having the world turned upside down?

2. Why were Cornelius and Peter so shocked to meet each other (Act 10:24-45)? What finally persuaded Peter that it was right to baptize non-Jewish believers? Do these kinds of interventions by the Holy Spirit still happen in the church today?

3. John D. Rempel writes, “Too much talk about God trivializes God’s reality,” and, “We squirm at calls for evangelism that seem triumphalistic and condescending.” Do you agree? Have we become too reluctant to talk about our faith? Can silence be an important form of witness? How do we know when is the time to keep silent and when is the time to speak?

4. How can we encourage our congregations to listen for the voice of the Holy Spirit? Are we willing to take a risk if we do hear the voice of the Spirit?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.