Advent, according to one definition, is “the arrival of a notable person, thing or event.” Yet along the way, we’ve come to associate Advent not with arrival, but with waiting.

In our homes, Advent is a time of preparation. We shop for presents, hang wreaths, display cherished nativity scenes and decorate trees. We bake cookies, buy turkeys, prepare stuffing and set the table. And we await the arrival of family and friends.

In our churches, choirs rehearse new anthems and beloved carols, children don bathrobes and memorize lines, pastors search for innovative ways to tell the familiar story. And we light candles as we count the weeks until that special day that marks the arrival of that “notable person.”

For whom are we waiting? The obvious answer is Jesus. Or is it?

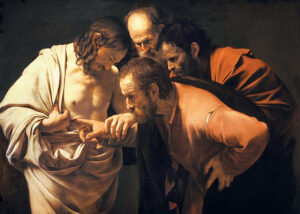

It wasn’t obvious to the Jews during the Roman occupation of Palestine. For centuries they’d been waiting for the promised Messiah. But when Jesus came along, it wasn’t at all clear that this carpenter from Nazareth was, in fact, the one they were waiting for. From our post-resurrection perspective of faith in Jesus, it’s hard to understand how they missed it.

Lest we be too critical, even John the Baptist had doubts about Jesus’ claim to the Messiah title. Matthew 11:2-11 records that after Herod had John imprisoned, John sent his disciples to ask Jesus: “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?”

How could this be? John the Baptist fulfilled Isaiah’s prophecy: “Prepare the way for the Lord; make straight in the desert a highway for our God.” He was baptizing and preaching repentance because he knew the Messiah’s arrival was imminent.

When Jesus came to John for baptism, John seemed to have it figured out. In fact, he tried to deter Jesus. “I need to be baptized by you,” John told Jesus, “and do you come to me?” But Jesus insisted it was the right thing to do. So John baptized him and presumably witnessed God’s Spirit descending on Jesus and heard God’s voice saying, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.”

What happened, then, between Matthew 3, when John baptized Jesus, and Matthew 11, when John sent his disciples to ask whether Jesus was the Messiah or not? What happened that shook John’s confidence in Jesus? I wonder if John’s uncertainty had something to do with his messianic expectations.

People flocked to see John. It was like an old-fashioned revival meeting, without the tent, and people answered the altar call even without the choir singing “Just As I Am.” But when the Pharisees and Sadducees decided to check out this desert evangelist, things got really interesting. “You brood of vipers!” John challenged them. “Who warned you to flee from the coming wrath?” Aside from the obvious fact that John didn’t think highly of these religious leaders, the last part of his question—“the coming wrath”—reveals something about John’s expectations of the Messiah.

John dared them to “produce fruit in keeping with repentance,” and warned them that being children of Abraham wouldn’t be enough to save them. He said, “The axe is already at the root of the trees, and every tree that does not produce good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire.”

And then he spoke of the one whose way he was preparing: “He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and with fire. His winnowing fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing floor, gathering the wheat into his barn and burning up the chaff with unquenchable fire.”

Again, from our post-resurrection, post-Pentecost perspective, it may seem clear to us that John was talking about Jesus. Indeed, John was talking about the Messiah, but what kind of Messiah was he expecting? It sounds like John’s Messiah was someone who would upset the existing order, quite possibly with violence, and root out what was evil or unproductive.

John’s expectations of the Messiah weren’t all that different from those of the Pharisees and Sadducees he rebuked. The Jews—John included—were waiting for a political leader who would overthrow their oppressors and restore the free nation of Israel to the glory it knew under King David.

From everything John could see, Jesus wasn’t on that trajectory. The InterVarsity Press (IVP) New Testament Commentary Series states: “Jesus’ ministry had so far fulfilled none of John’s eschatological promises. . . . It is no wonder that John doubted, and that John’s questions arose when he heard of Jesus’ deeds, not in spite of them.”

John Oakes, a Christian apologist and blogger at a site called Evidence for Christianity, says it’s not surprising the Jews were waiting for a conquering Messiah. Many prophetic passages speak of the emergence of this kind of leader. However, passages such as Isaiah 53 describe a very different Messiah: a suffering servant. Oakes writes: “It seems the Jews did not tend to pay nearly as much attention to this role of the Messiah. This . . . is human nature. Humans want their heroes to conquer and to offer great things to the people, not to suffer and die.”

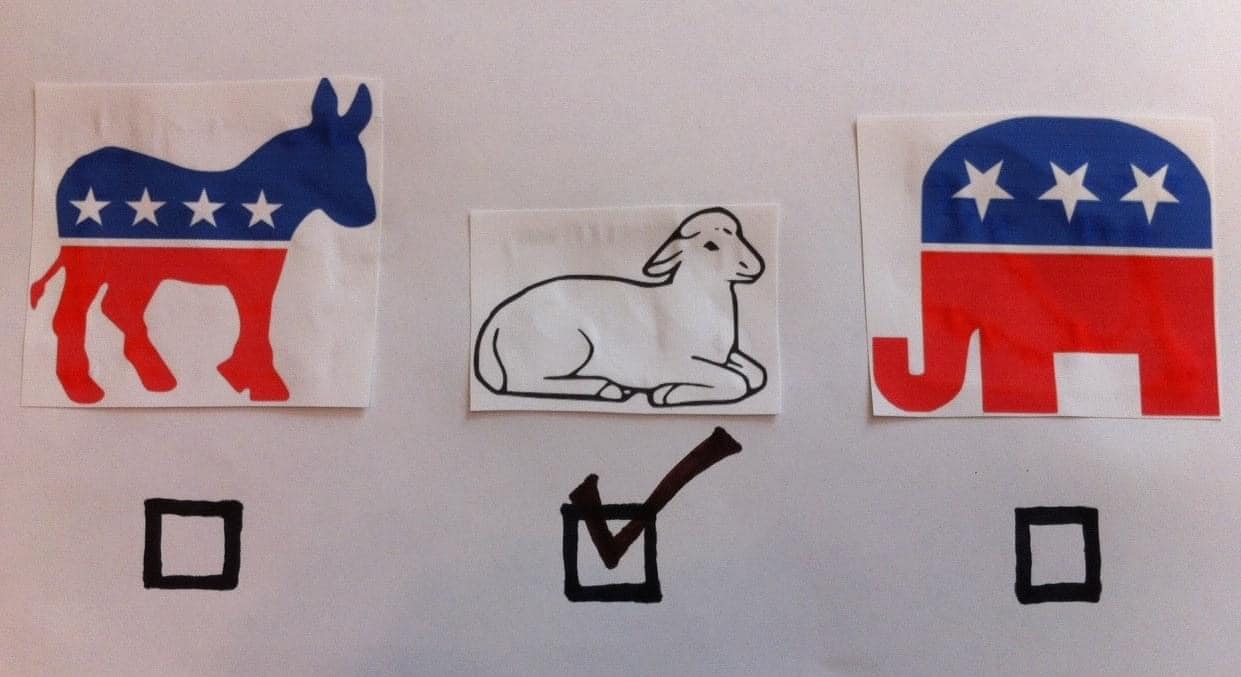

Jesus was not the kind of Messiah whom John the Baptist was expecting. But Oakes suggests he may not be the kind of Messiah we’re waiting for either. “Many make him into a cosmic bellhop—delivering blessings and solving all problems,” writes Oakes. “Theirs is the Jesus of name-it-and-claim-it: the prosperity gospel. Others who have strong convictions about social justice make a Jesus to their liking. Still others, premillennialists, have him coming back to be the head of a revived Jewish kingdom at the end of time. The lesson for us is that we, too, are tempted to form the Messiah in our own image.”

Perhaps we’d do well to examine our own expectations. Our world is filled with fear and uncertainty, characterized by the politics of division and ever-greater economic disparities. It’s tempting to look for a “Super Jesus” who will overthrow the Donald Trumps and the Kim Jong-uns of this world, and usher in an era of justice and peace.

But Jesus wasn’t that kind of Messiah. When John’s disciples asked, “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” Jesus’ answer was a gentle reminder that John’s image of the Messiah was incomplete. “Go back and report to John what you hear and see: The blind receive sight, the lame walk, those who have leprosy are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the good news is proclaimed to the poor.”

Here Jesus alludes to both Isaiah 35:5-6 and Isaiah 61:1. The IVP New Testament Commentary Series says that, in alluding to these passages, Jesus “reminded John’s disciples that the works he was performing might be less dramatic than a fire baptism, but Isaiah had already offered them as signs of the messianic era.”

We don’t know whether John found comfort in Jesus’ answer, but we know Jesus deeply respected John. In Matthew 11:9-10, he identifies John as a prophet and his own forerunner. In verse 11, he says, “among those born of women no one has arisen greater than John the Baptist; yet the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he.” This surprising statement isn’t meant to lower John’s status, but rather to elevate the lowly among Jesus’ followers. It is completely consistent with Jesus’ messianic mission.

It wasn’t that John got it wrong. Jesus’ followers were baptized with the Holy Spirit and with fire on the day of Pentecost. And that Holy-Spirit baptism empowered them to carry out the work Jesus called them to do—that of making disciples of all nations. The Book of Acts is filled with stories of Jesus’ followers healing the sick, raising the dead, and preaching the good news to the poor, the rich and anyone else who would listen.

Jesus’ followers also formed communities that worshipped together and cared for each other. They did this because Jesus had told them, “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.” Because of their love for each other, and their willingness to include everyone, regardless of race, class or gender, they started to be known by a new name: Christians.

According to Relevant, a Christian magazine and website, the –ian suffix meant “belonging to a party.” A Christian, then, was someone who belonged to Christ’s party. Perhaps because Jesus’ followers wanted to be like Christ, they eventually embraced the new name.

Sadly, those who call themselves Christian haven’t always lived up to the name. Christians have excluded people because of race, class and gender. Christians have ignored the needs of the hungry and the hurting. Christians have waged war in the name of Christ.

Again, according to Relevant, “the ‘Christian’ label is ever-redefining based on the reputation we give it.” The world has expectations of us. Are we up to the challenge of giving the name “Christian” the reputation it deserves? When we love each other, when we welcome our neighbours, introduce them to Jesus and make disciples of them—then we are the embodiment of Christ. Then we are Christian.

For discussion

1. What are the rituals or preparations at your house as you get ready for the Advent/Christmas season? Which rituals or preparations are most time-consuming? Which are most tedious? Which are your favourites? Which are the most important?

2. Donna Schulz writes that, “when Jesus came along, it wasn’t at all clear that this carpenter from Nazareth was, in fact, the one they were waiting for.” What kind of Messiah were the Jewish leaders expecting? Do you think John the Baptist was disappointed in Jesus?

3. Schulz quotes John Oakes, who writes, “Humans want their heroes to conquer and to offer great things to the people, not to suffer and die.” Do you agree? What does it mean to “form the Messiah in our own image”? Do we expect Jesus to deliver blessings and solve all our problems?

4. If we are followers of Jesus, the suffering servant, does that mean the church needs to see suffering as part of its mission? Is the church in Canada suffering today? Is suffering included in the Christmas message?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.