What do we do when we disagree with people in our church? There are lots of reasons to disagree. We can disagree about how we talk about salvation, about who we should include or not include, about political views, or even about vaccination. Across North America, we see issues dividing congregations and conferences.

When people in the church disagree, we have choices on which biblical passages guide our actions. The story of the wheat and the tares (Matthew 13:24-30) is not often one we consider. How might our history in the Mennonite church be different if we took this parable to heart?

A farmer plants a crop with good wheat seed, but an enemy comes and plants other seeds in the ground. The Greek word that we translate into English as tares or thistles is zizania, which is a type of weed that looks very much like wheat, except that its seeds are black and inedible. So, as the wheat and zizania plants grow, you would not notice that the difference until they start to bear seed. By that time the roots are all intertwined.

Farm workers who try to root out the zizania are going to pull up the wheat too. They can get rid of the zizania, but they won’t get any harvest at all. That’s why the farmer instructs the workers to leave the tares to grow until the harvest time, when the harvesters will separate the grain from the tares.

Waiting is central to this parable. But when conflict surfaces in churches, often people do not want to wait.

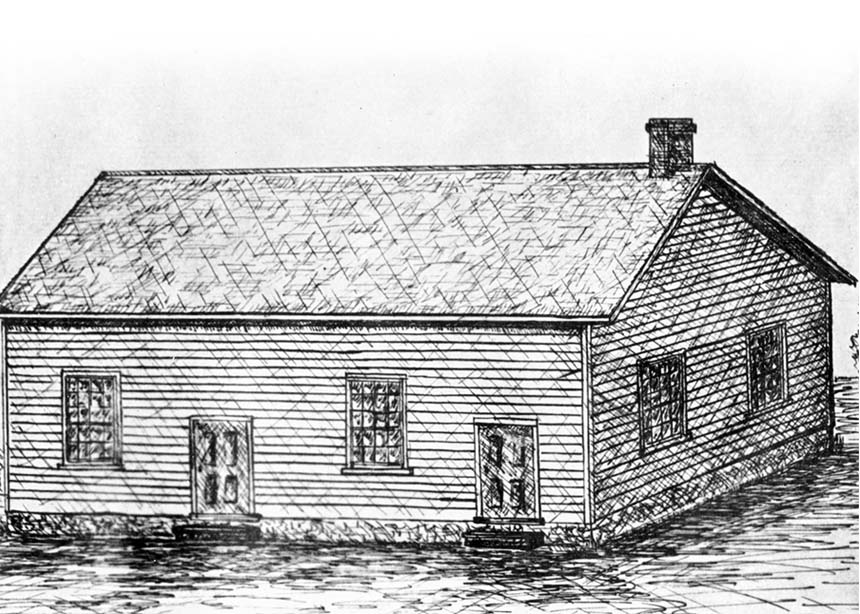

The First Mennonite Church in Vineland, Ont., where I attend, was the first Mennonite church in Canada, established in the early 1800s. Given its long history, that church has gone through more conflict than most congregations. What can we learn from its story? Here are three examples of when people gave up waiting and, instead, pull up the wheat and the tares, tearing apart the congregation.

Reforming the church in the 1840s

In the late 1700s, Mennonite farmers from Pennsylvania settled on an Indian trail close to Twenty Mile Creek in the Niagara Peninsula. They worshipped in what was then called the Meyer meeting house (later anglicized to Moyer). Within 40 years of its beginning, the congregation faced a crisis.

An evangelical reform movement had been sweeping through North America. It blew into the Niagara Peninsula in the 1840s with Mennonite preachers from the United States. These reformers were called, not surprisingly, the “Reformed Mennonites” (unrelated to the group called Reformed Mennonites today).

Reformers taught about the importance of individual salvation, and a more Spirit-filled life. Preaching was often accompanied by dramatic conversions of people from Mennonite congregations. Some members of the Moyer church were converted to this new way of thinking about their faith. These newly inspired Mennonites wanted to hold prayer meetings during the week in their homes.

By 1848, people in the congregation were bitterly divided. There seemed to be two different ways of talking about faith, and leaders had to decide whether these new evangelical ideas, with their more emotional tone, should be tolerated, or whether the old pattern of faith was better.

A minister at the Moyer meeting house, Daniel Hoch, had become part of this new way of talking about faith, but not everyone in the church agreed with him. Bishop Benjamin Eby was brought in to try to reconcile the opposing factions, but he was unsuccessful. By 1850, the divisions were finalized. Those who left the Moyer church joined with other likeminded Mennonites and formed a new conference called, not surprisingly, the New Mennonite Conference.

You might think that people just cordially decided to disagree and go their own way, but that’s not what happened in this conflict. Bishop Eby had officially silenced Daniel Hoch and others like him. Hoch stated that the praying and the non-praying parts of the church divided. He called on people in the Moyer church to confess their sins, repent and be saved. Reformers thought that the people who did not join them were not even Christian.

How would a parable like the wheat and the tares have spoken into a situation like this in the 1840s? Did they tolerate each other and wait patiently to let the angels decide at the last harvest who was right? Definitely not!

Leaders wanted everyone to think the same way. Both sides of the conflict wanted to root out “heretical” Mennonites. Perhaps they were inspired by words from Jesus in Matthew 5:30: “And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to go into hell.”

Looking for order in the 1880s

In the late 1880s, conflict again tore apart Moyer Mennonite Church. The innovations that had been so rigidly resisted in the 1840s had become mainstream. Congregational life at Moyer Mennonite now included evangelical practices like prayer meetings, Sunday school and singing in four-part harmony. Leaders were also starting to preach in English, as opposed to Pennsylvania Dutch.

Some at Moyer Mennonite had had enough. They could not tolerate these innovations; they liked the old ways better. People from various Mennonite churches gathered to resist, forming their own churches that followed the old order of congregational life. They called themselves, not surprisingly, the Old Order Mennonites.

For the Moyer church, that meant that the people who wanted the old order of doing things left the meeting house and built their own building on the other side of the church property. These churches were within singing distance of each other.

Once again, the community was torn apart, with families and friends separated and divided by animosity. Once again, the parable of the wheat and the tares, with its counsel for waiting for God to judge, was the last thing on people’s minds.

Listening to the Spirit

Almost a century later, in the 1970s, the charismatic movement was sweeping through churches in North America. At the Moyer church (renamed The First Mennonite Church), some people got caught up in new ways of thinking about God. There was an emphasis on the Holy Spirit and on spiritual gifts, such as speaking in tongues and prophesy.

Once again, people were critical of each other for either following this new way of thinking and wanting these spiritual gifts, or for rejecting them.

A charismatic minister that the congregation called was the focus of some of the tension. Part of the congregation liked the minister, while another part thought he was misguided. Some people joined the church during this renewal movement, but many people left. This conflict in the 1970s left the congregation with such a low membership that its future was in doubt. Leaders wondered whether it was time to close the doors of this congregation permanently.

Learning from hindsight

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy for Christians today to look back at all the divisions in this congregation’s history and say, “It would have been better for people to tolerate each other. Probably all those people were following God in their own way!”

But in the midst of conflict, it’s surprisingly hard to discern tares and wheat. Who is sowing evil seeds? Were the people who wanted prayer meetings and Sunday schools sowing evil seed? Was the evil seed singing in harmony, preaching in English, or speaking in tongues?

Maybe the evil seed is the judgmental attitude and pride that makes us think that we know better than our neighbour about what pleases God. Maybe the evil seed is the attitude that everyone must think exactly the same way, that we must have a “pure” church. These seeds bear fruit that prompts us to push people out, or we leave and start our own new, better church, that we will probably call “Better Mennonite Church.”

How easy it is to look at someone else in the church and think, “They are wrong.” Then it’s only a hop, skip and a jump to think, “They aren’t Christian,” and there we are in the garden with our trowel, digging up those nasty tares, disregarding the fact that we are uprooting the wheat that was so carefully planted.

It is sometimes complicated to read the Bible and figure out a way forward. Which stories do we read and which do we disregard? How can we hear what the Spirit is telling our church if we decide that God can’t possibly be speaking to those with whom we disagree?

The First Mennonite Church in Vineland has survived for 200 years, and remembering our history is important to those of us in the church. We can anticipate that the Spirit will bring changes, and that there will be conflict. How will we react the next time this happens?

Carol Penner teaches practical theology at Conrad Grebel University College, Waterloo, Ont. This is an adaptation of a sermon she preached at The First Mennonite Church on Aug. 8, 2021. For those who want to read more about this history, she recommends: A Brief History of the Mennonites in Ontario, by L. J. Burkholder, and In Search of Promised Lands: A Religious History of Mennonites in Ontario, by Samuel Steiner.

For discussion

1. Have you ever experienced so much conflict in a church that a group of people chose to leave? How much of the disagreement was due to theological differences? How did emotions play a part? Do you think that time and patience could have resolved the conflict?

2. Carol Penner points to Jesus’ parable of the wheat and the tares in Matthew 13. Does this parable mean that false doctrine should not be challenged in the church? In church life, what does it mean to wait for the harvest before separating the wheat from the tares? Are there situations when it is important not to wait?

3. Penner describes three divisions in her church where ardent spirituality was part of the disagreement, even to the point of questioning the other side’s Christianity. Why would fervent religiosity be such a point of conflict? Why might it be harder to be patient when we are feeling zealous? Are church splits always harmful?

4. Since the early church, Christianity has divided into many denominations. In what ways has this diversity been beneficial and how has it been destructive? Do you see greater cooperation than in the past?

5. When you find yourself in conflict with others in your congregation, what should you remember?

—By Barb Draper

Related article:

The third side of church splits

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.