“Good King Wenceslas” is not the most sing-able of carols and the lyrics are on the King James end of archaic. You may have assumed this 10th-century legend is about the spirit of the Yule and putting a penny in the old man’s hat. Let’s look again. See what you think of the conversion of his servant, the Page. (You can find the lyrics after the discussion questions below.)

On the Feast of Stephen the King peers out his window into the frozen world and sees a peasant struggling against the cruel, cold night. The King asks his Page, “Yonder peasant, who is he? Where and what his dwelling?” He is asking the Page to help him know his kingdom’s needs. The conversion of the Page begins not when he stares down into his own navel and realizes his own sinfulness, but when his eyes are lifted to see the world as the King sees it, in need of love.

So “Page and Monarch forth they went, forth they went together.” This is the incarnation at Christmas. Think of God as King Jesus going out into a hostile world to bring good news to the poor and proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour (Luke 4:18-19). The King makes this decision himself. The Page has no interest in yonder freezing peasant until the King points him out and draws the Page into his love and out into the world with him. The Page says, in effect, “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word” (Luke 1:38).

But then the drama of conversion begins. It’s a drama not because yonder peasant is so resistant to flesh and wine. Out on the expedition the Page flounders about in weakness, unable to keep up with the King on his icy mission. The Page discovers the depth of his sin as he seeks to track with his King on this errand of mercy.

The Page does not have a “hit-rock-bottom” experience by the fire inside the castle that might call out the King’s blessing on him. Out in the blizzard, on the way to the poor, the Page realizes that if salvation comes by accompanying the King out seeking the lost, he himself is a goner. “Fails my heart, I know not how, I can go no longer.”

Then cries the King over the wail of the storm: “Mark my footsteps, my good Page. Tread thou in them boldly. Thou shalt find the winter’s rage freeze thy blood less coldly.” In other words, quit thrashing around by yourself in this quest; walk, instead, in my footsteps.

This is grace. Grace can be the merciful acceptance of the sinner who has not earned love. It can also be the command of orientation, and the assurance of the King’s presence for a lost “under-saviour.” Rather than bucking the snowdrifts on his own in trying to feed the poor, the Page is beckoned to fall in behind the King, who pioneers a path.

But note again, there is no relieving the Page of the mission. The King does not stop and say: “First attend to thine own soul, my dear Page, and then come back hither into the gale.” Salvation is simply falling in behind the King tramping out with meat to a peasant. To be a Christian is to become a person who keeps up with the King. But can we be saved by merely following the King?

Here comes the Christmas miracle. The Page sets his foot down into the shoe prints of the King and knows immediately that these are no ordinary tracks: “Heat was in the very sod which the saint had printed.” As the Page fits his own feet into the Master’s footprints that are pointed toward the freezing peasant, he finds a Spirit-heat radiating from these tracks. This is our first indication that this King is more than just an ordinary good man.

The King holds a power to energize or grace a path into the world. The very soil this King touches as he strides toward the poor becomes the vent through which the warmth of Spirit-fire and the assurance of salvation enter the frail Page.

“Therefore, Christian men, be sure, wealth or rank possessing, Ye who now will bless the poor, shall yourselves find blessing.” If we cut that last phrase loose from the rest of the song, we might suspect a legalism at work here, a works-righteousness in which we are saved if we give enough alms to the poor. It is true that, according to this song, the Page finds “blessing”—which I am interpreting as salvation—only in joining the King’s trek into the world to help the poor. But this is not legalism, and here we come to an insight that, I believe, Scripture points to in talking about salvation.

Let me stereotype to make a point:

• The Protestant way would have the Page go through a saving experience back at the castle. There he would receive the assurance of salvation and the anointing of the Spirit. Then, out of gratitude for this wonderful grace, he would rush out to help the peasant. But even if he failed to reach the peasant, his salvation would be secure. He was saved back at the castle already, before the freezing foray.

• In a legalist plan of salvation, on the other hand, the Page, back at the castle would be burdened by his need to impress the King. Seizing upon a plan, he would rush out to flounder in the snow, hoping the King would notice his extreme effort and grant him holy rest when he is finally dragged, frozen, stiff and dead, back into the castle, having given his all.

• But then I think this 10th-century legend is similar to the old Anabaptist view of salvation. The King invites us to go out with him into the world to be his apprentice, his partner, in bringing hope to the poor. On the way, as the strength to overcome the world’s never-ending winter, we receive unmerited grace, which is the Spirit-heat and assurance of partnership needed to share in the King’s mission.

Here, grace is the Spirit’s power to be joined mystically and practically with Christ in his love for people. We are saved by grace from all our sin, but this sin is not some navel-gazing infirmity we nurse by the fire back at the castle. Sin is our hopeless inability to truly love our fellow church-member, neighbour or the poor around us, as Christ does. As we seek to love the poor we are thrown against our own poverty. To be saved is to fall in behind the King. In that surrender, we find grace, forgiveness and assurance as the power to love.

Hans Denk, an Anabaptist mystic, said: “Whoever has recognized the truth in Christ Jesus and obeys it from the heart is free from sin, although he is never free from temptation. It is impossible for him to walk firmly in the way of God unless he be strengthened by God.”

We live in a culture that, at some level, wants to help the poor. What we find as the church is heat in the sod. In Christ there is power and hope for those who find the world’s problems insurmountable and ever-increasing. We have found we cannot track with Christ without this Spirit-heat.

“Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light (Matthew 11:29-30.

Layton Friesen is an EMC minister, a doctor of theology student at the Toronto School of Theology, and a member of the Toronto Mennonite Theological Centre. Originally published in the December 2015 issue of the Evangelical Mennonite Conference Messenger.

For discussion

1. Do you know the words to “Good King Wenceslas”? Where did you learn them? How often do you hear it sung? Is it a favourite of anyone you know? Do you agree with Layton Friesen that it is “not the most sing-able of carols”?

2. Do you sometimes feel like the Page, finding it difficult to make your way through the snow while carrying a bundle? What situations make our lives particularly challenging? In what ways is King Wenceslas a Christ figure? What does it mean to walk in the footsteps of the King?

3. Friesen suggests that this song is an image of salvation as apprenticeship, which is different from salvation as private conversion or legalism. He says, “I think this 10th-century legend is similar to the old Anabaptist view of salvation.” Do you agree? How does this view of salvation bring together grace and action?

4. Friesen writes about “Spirit-heat” that radiates from the Master’s footprints. Can you think of examples of how Christians have experienced this “Spirit-heat”? What does this carol have to say about our relationship to Christ and our view of the world?

—By Barb Draper

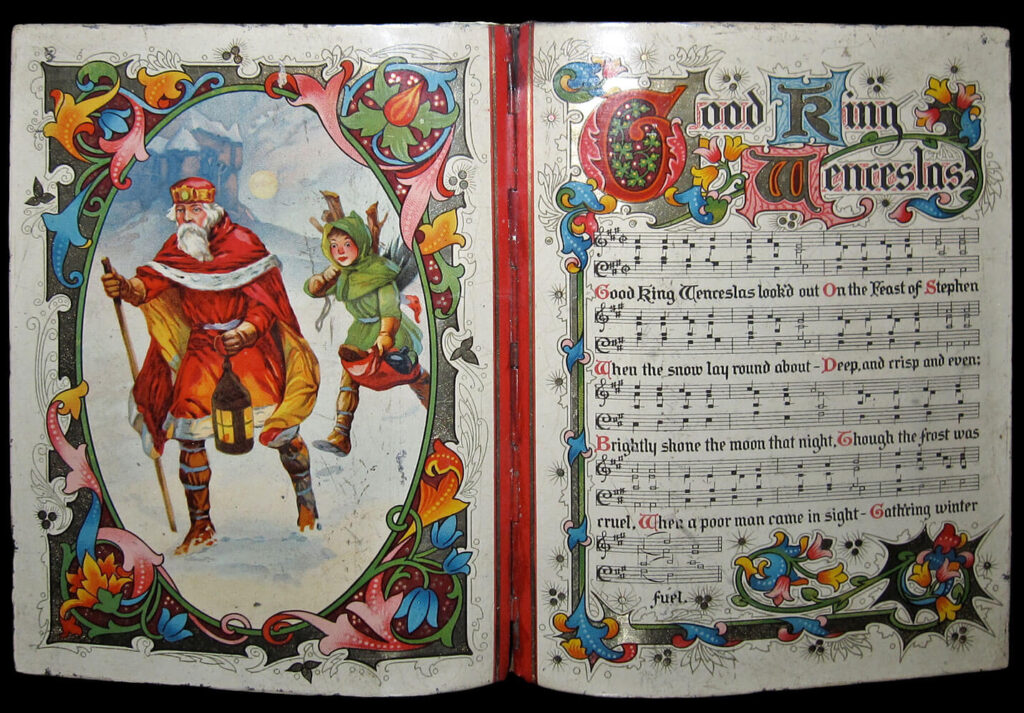

Good King Wenceslas

Good King Wenceslas last looked out

On the feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about,

Deep and crisp and even.

Brightly shown the moon that night,

Though the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight,

Gathering winter fuel.

“Hither, page, and stand by me.

If thou know it telling:

Yonder peasant, who is he?

Where and what his dwelling?”

“Sire, he lives a good league hence,

Underneath the mountain,

Right against the forest fence

By Saint Agnes fountain.”

“Bring me flesh, and bring me wine.

Bring me pine logs hither.

Thou and I will see him dine

When we bear the thither.”

Page and monarch, forth they went,

Forth they went together

Through the rude wind's wild lament

And the bitter weather.

“Sire, the night is darker now,

And the wind blows stronger.

Fails my heart, I know not how.

I can go no longer.”

“Mark my footsteps my good page,

Tread thou in them boldly:

Thou shalt find the winter's rage

Freeze thy blood less coldly.”

In his master’s step he trod,

Where the snow lay dented.

Heat was in the very sod

Which the saint had printed.

Therefore, Christian men, be sure,

Wealth or rank possessing,

Ye who now will bless the poor

Shall yourselves find blessing.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.