On a spring morning in 1970, Henry Regier walked out of the residence assigned to guest lecturers at the University of Wisconsin and turned east. Student riots related to the Vietnam War had broken out on campus, and the night before National Guards with bayonets had deployed tear gas. Wanting to avoid the brewing violence that morning, Regier walked away from campus towards a used book store.

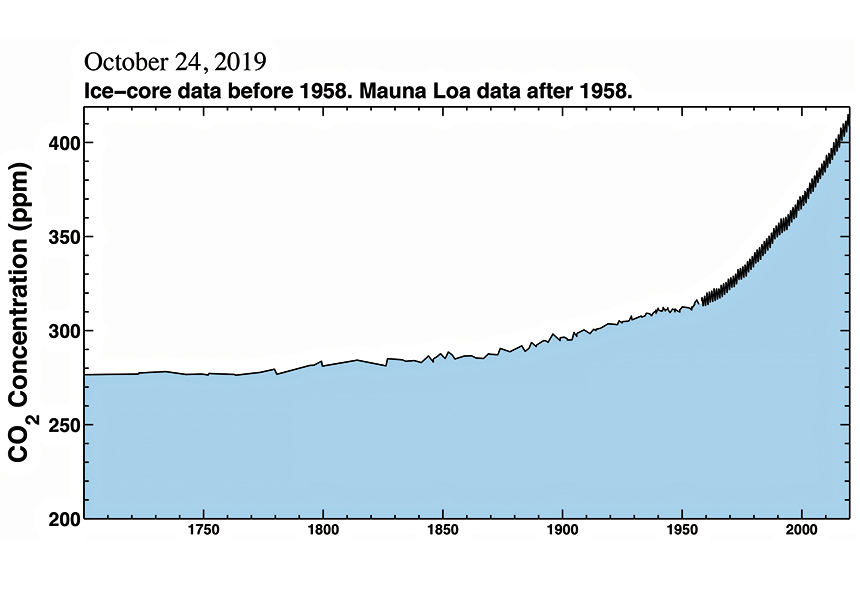

There, he happened upon a book by C.R. Van Hise, a former president of the University of Wisconsin. The 1911 book, which Regier still has, proposed that the combustion of large amounts of coal over time would result in a milder climate.

“In the light of all my personal experiences and education,” Regier recalls, “I judged that Van Hise had stated a plausible hypothesis.”

Van Hise, as Regier notes, had built on discoveries of earlier scientists, like Eunice Newton Foote, whose 1856 paper discussed heat trap gases, and S. Arrhenius, who likened atmospheric carbon dioxide to a hothouse in the 1890s.

For Regier, the discovery of Van Hise’s book contributed to what became a nearly 50-year professional and personal interest in climate-related science and practice.

Now 89 and living in Guelph, Ont., Regier served as a professor of zoology and director of the Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Toronto. In 2008, he was named a Member of the Order of Canada for his contribution to the “protection and restoration of the Great Lakes,” and for his involvement in environmental stewardship internationally. He also served as author and peer reviewer for studies that were part of the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was a co-recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize.

Regier repeatedly emphasizes that his work relied on extensive collaboration with a range of other researchers. “I’m a Mennische farm boy who compulsively networked with many others,” he says via email, “sharing in successes and failures.” His ongoing academic work focuses on networking itself.

While the strained tones of climate activists may be warranted, the perspective of a seasoned scientist and ardently practical farm boy registers differently. As he shared at Niagara Christian Collegiate this past May, Regier sees science as a “persistent, disinterested pursuit of truth,” quoting T.A. Goudge, a former University of Toronto philosopher. Science is to be co-operative, rooted in observation and logical, and any conclusions reached are “intrinsically provisional and susceptible of further refinement or correction as inquiry is continued.”

This has been Regier’s approach to climate. His views have more depth and less edge than many climate campaigners. He matter-of-factly recalls dialogue with respected colleagues who hypothesized that the climate was cooling.

Regier notes that temperature was a thread in his life, well before Van Hise landed in his lap. He was born in “the first house that was built in a wild township of northwest Alberta” near the edge of what is now the oil patch. There, temperature mattered. Not only in terms of firewood supply, but which crops would produce there, something his father experimented with carefully.

The theme of temperature continued through his studies and then into his study of how climate warming would affect fish.

Given the link between temperature and carbon in its various forms, Regier similarly traces his personal and family history in relation to carbon fuels, starting with his ancestors, the Koop Brothers, who burned coal in the process of manufacturing farm implements in present day Ukraine starting in the 1860s. Later, his mother, “turned over the manure blocks in the barnyard to dry them to serve as fuel in their home’s stove . . . even on the morning of her wedding day in 1919.” And on the family’s Alberta homestead in the ’30s, kerosene for lamps, and grease used for wagon axles and the like, were the only fossil carbons they used.

This sort of practical and historical approach has marked Regier’s career.

As science pointed increasingly to the stress that rapidly increasing global population was placing on the planet, Regier helped spearhead a group that organized a major 1968 “teach-in” on population, attracting world-class thinkers.

Regier’s scientific concern about population had a personal basis. After he and his late wife Lynn had three children, they decided in 1961 that he would have a vasectomy, which was illegal at the time. The Regiers were later among various people profiled in a Chatelaine magazine article about vasectomies, and Regier was invited to work with the government on related policies.

Over several years of sporadic correspondence I have had with Regier, a term that continually re-surfaces in his stream of ideas is “praxis,” which Merriam-Webster defines as “practical application of a theory.” Regier talks about personal praxis, “Jesus praxis,” and, most often, “Mennonite praxis.” The latter points, in part, to the “voluntary democratic communitarianism” of his ancestors in the Polish wetlands, whose collective, conservation-minded care of the land could inform practice in today’s warming world.

In 1970, Regier considered the notion of climate warming a “plausible hypothesis.” Today, it is for him a personal passion rooted firmly in science and a centuries-old Mennonite heritage of practical caring.

LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0geyBtYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAzMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbiB7IGJvdHRvbTogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcik7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDAgMCA1cHggMDsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IHVse2xpc3Qtc3R5bGU6bm9uZTttYXJnaW46MCAwIDEuNWVtIDA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse21hcmdpbjowICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3RvcDowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHtncmlkLXJvdy1lbmQ6dW5zZXQgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6OmJlZm9yZXtjb250ZW50OiIiO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3BhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxsOjptYXJrZXJ7Y29udGVudDoiIn0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgaW1ne2hlaWdodDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7d2lkdGg6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3AgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7YWxpZ24tc2VsZjplbmR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczpyZXBlYXQoMTIsIDFmcil9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1jb2xsYWdlIGltZ3toZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MDtncmlkLWF1dG8tcm93czoxcHg7b3BhY2l0eTowfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgaW1nLC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpZnJhbWUsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHZpZGVvey1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt3aWR0aDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7ZGlzcGxheTpibG9ja30udGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2FwdGlvbntwb3NpdGlvbjphYnNvbHV0ZTtib3R0b206MDt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjYpO3BhZGRpbmc6NXB4IDJweDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtjb2xvcjojMzMzfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uOmVtcHR5e2JhY2tncm91bmQ6dHJhbnNwYXJlbnQgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgZmlndXJle2hlaWdodDoxMDAlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IGltZ3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDoxMDAlOy1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3Zlcjt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjpib3R0b219I2xlZnQtYXJlYSB1bC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5e2xpc3Qtc3R5bGUtdHlwZTpub25lO3BhZGRpbmc6MH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9uIHsgYm90dG9tOiA1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1nYWxsZXJ5PSIzZWVlZDNiYjg2MmQ0NmJiOTg4MzcyNTRmYWVmZGE3NiJdIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IHsgcGFkZGluZzogMCAwIDVweCAwOyB9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgdWx7bGlzdC1zdHlsZTpub25lO21hcmdpbjowIDAgMS41ZW0gMDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGx7bWFyZ2luOjAgIWltcG9ydGFudDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLXJvd3M6YXV0byAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7dG9wOjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQ6bm90KC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkLS1ub2Nyb3ApIC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jZWxse2dyaWQtcm93LWVuZDp1bnNldCAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbDo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6IiI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZDpub3QoLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCkgLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NlbGw6Om1hcmtlcntjb250ZW50OiIifS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1ncmlkOm5vdCgudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wKSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTstby1vYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXJ9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCBpbWd7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG8gIWltcG9ydGFudDt3aWR0aDphdXRvICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWdyaWQtLW5vY3JvcCAudGItZ2FsbGVyeV9fY2VsbHthbGlnbi1zZWxmOmVuZH0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tZ3JpZC0tbm9jcm9wIC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudHtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOnJlcGVhdCgxMiwgMWZyKX0udGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tY29sbGFnZSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnR7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLWNvbGxhZ2UgaW1ne2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnl7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDowO2dyaWQtYXV0by1yb3dzOjFweDtvcGFjaXR5OjB9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50e3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5LS1tYXNvbnJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBpbWcsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgLnRiLWJyaWNrX19jb250ZW50IGlmcmFtZSwudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgdmlkZW97LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3dpZHRoOjEwMCUgIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmJsb2NrfS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5X19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7cGFkZGluZzo1cHggMnB4O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO2NvbG9yOiMzMzN9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb246ZW1wdHl7YmFja2dyb3VuZDp0cmFuc3BhcmVudCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5IC50Yi1icmlja19fY29udGVudCBmaWd1cmV7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCV9LnRiLWdhbGxlcnkgaW1ne3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOmJvdHRvbX0jbGVmdC1hcmVhIHVsLnRiLWdhbGxlcnl7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZzowfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnlfX2NhcHRpb24geyBib3R0b206IDVweDsgfSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdhbGxlcnk9IjNlZWVkM2JiODYyZDQ2YmI5ODgzNzI1NGZhZWZkYTc2Il0gLnRiLWdhbGxlcnktLW1hc29ucnkgeyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDogNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1nYWxsZXJ5W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ2FsbGVyeT0iM2VlZWQzYmI4NjJkNDZiYjk4ODM3MjU0ZmFlZmRhNzYiXSAudGItZ2FsbGVyeS0tbWFzb25yeSAudGItYnJpY2tfX2NvbnRlbnQgeyBwYWRkaW5nOiAwIDAgNXB4IDA7IH0gIH0g

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.