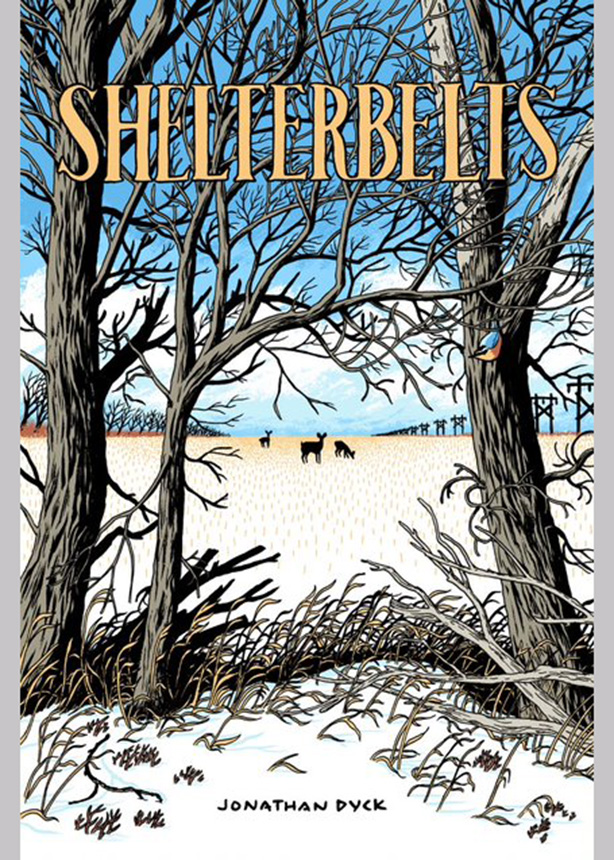

Four panels on page 108 of Jonathan Dyck’s graphic novel Shelterbelts are stuck in my mind.

I’ve studied these black-and-white images so closely that they appear something like a photo negative when I close my eyes. The first is a wide shot of poplar trees in a field of grass; the second is a medium shot of a sky with a few leaves falling off of branches; the third shot pulls out to show wildflowers leading from a line of birches; and the fourth shot zooms in to waving tall grass. Between the panels, three speech bubbles say: “This place. / I feel like I know it. / Like it knows me.”

That description, though, doesn’t quite capture why I find those four panels so affecting. There’s something about the integration of Dyck’s words and pictures that strikes me as simultaneously mournful and hopeful.

I felt the need to stare at so many pictures in Shelterbelts—not because they aren’t clear, but because they are almost too clear. That clarity not only shows a little about how southern Manitoba works, it shows a little about how my relationship to my own Mennonite identity works. Until I read this book, I didn’t know that anyone saw my hometown the way I do. But Dyck does. And he sees much more than that. In a way, he sees me.

With an episodic narrative—Shelterbelts reads like a collection of interconnected short stories—Dyck considers what it means to love your neighbours in a small, rural, predominantly Mennonite town. Each short story takes up a crucial issue: What does it mean to love your neighbour who permits the Armed Forces to recruit at the high school? What does it mean to love your neighbour who denies rights to people who are LGBTQ+? What does it mean to love your neighbour who supports oil pipelines? That is not to suggest this is just book of big ideas.

Dyck presents your neighbours through a series of people who feel more than a little familiar. In the first chapter, you meet the pastor of a Mennonite assembly that is losing members since he’s decided to preach a message of inclusion, you meet the daughter of that pastor whose decision to leave that assembly influenced her father’s decision, and you meet that pastor’s high-school-teacher friend who decides to demonstrate based on his religious convictions. Oh, and you also meet the pastor of an evangelical fellowship who’s decided to focus his message on church growth.

And there are 16 other main characters. All within a tight 248 pages!

Beneath the four panels I described above, two panels show Rebecca walking with her partner Jason through a landscape that they both fondly call their own. Rebecca was raised on the land, so it’s her home, but Jason’s ancestors had the land taken from them, so it’s also his home. The images are wordless, but the characters exchange a look of longing that shows all you need to know.

Dyck knows that if I, Mennonite by birth and by choice, truly want to understand myself, I must do the work to reconcile with the past. Shelterbelts shows that the past is simultaneously personal and political.

Shelterbelts arrives in stores next month. Visit conundrumpress.com.

Nathan Dueck teaches creative writing in Cranbrook, B.C. His most recent poetry collection, A Very Special Episode, was published in 2019.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.