Are more students struggling with mental health issues these days, or are they just better able to articulate their struggles than students once were? Jim Epp doesn’t know the answer to this question.

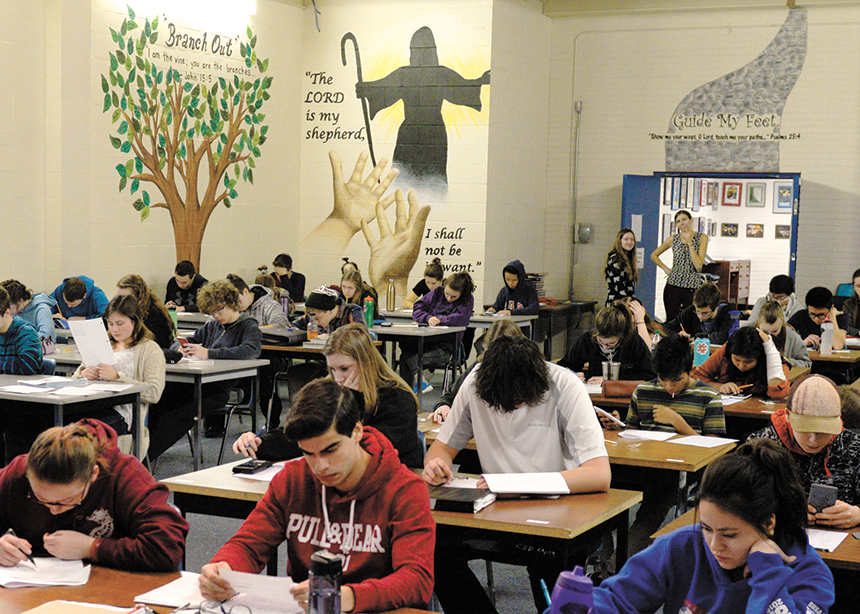

As principal of Rosthern Junior College (RJC), one thing he does know is that his students are not immune to mental illness of any kind. The most prevalent, he says, are depression, anxiety and panic attacks.

In his 32 years as a teacher and administrator at the school, Epp has seen students with eating disorders, self-harming behaviours and, very rarely, suicidal tendencies. But over the span of his teaching career, he has seen an increase in the fragility of students with regard to anxiety and stress.

“Social media is part of it,” he says. “The world never leaves them alone.” But the issue is complex, and social media isn’t the only factor. The world has changed, and so have the realities students face. “The work world is way different,” he says, “far less certain.”

Through chapel presentations and the Grade 11 Life Transitions class, which includes a unit on mental health, teachers invite students into conversations on the subject and work to de-stigmatize mental illness.

When students struggle with their mental health, staff direct them to local professionals and, as they seek counselling, staff make sure they get to their appointments. “It’s no different than taking them to the dentist,” says Epp.

But Epp and his staff can only do so much. As he points out, RJC is a school, not a mental health facility. “If a student presents [symptoms] beyond our capacity to help them, then we’re not the place for them,” he says. “We have to recognize the limits to what we can do.”

One thing RJC can do is to create an environment in which students feel they have a choice. This means being adaptable. For one former student, staying at the residential high school for a full week at a time was too much. Epp encouraged the student to try to stay until Wednesday each week. Eventually, the student was able to stick it out until Thursday and, finally, until Friday before going home for the weekend.

Epp and his colleagues encourage students “to find whichever one of us they feel safe with” as someone to talk to or just simply be with. For one student, a chair in Epp’s office is a safe place to sit when she suffers panic attacks. For many students, the residence deans create that safe place.

These days, Myrna Wiebe is RJC’s office administrator, but prior to taking on this role she spent a total of 11 years working as a dean. During those years, says Wiebe, she and her fellow deans maintained an open-door policy, making themselves available to students at all times. Sometimes students would come seeking advice; other times, they just wanted a listening ear.

Over the years, Wiebe has seen many students struggle with mental illness. And many have viewed taking medication for their illness as a source of embarrassment and shame. “Often they would say, ‘It’s not fair that I need to take meds to be normal,’ ” she says. “So they would stop taking their meds. It was so disheartening.”

Residence life is a double-edged sword for many students. On one hand, being part of a close-knit community can be a source of comfort and strength. On the other, living in close proximity with others can be an added source of stress. Even students who are happy living in the dorm may suffer because they don’t want to miss anything, and therefore don’t get enough sleep. Lack of sleep can significantly impact students’ mental health. “One of our biggest assets is the dorm,” says Wiebe, “and one of our biggest [liabilities] is the dorm.”

Both Wiebe and Epp acknowledge that faith plays a significant role in meeting the mental health needs of students. Wiebe views faith as “a large part of what motivates you to care when you’re very tired.” She recalls spending time in prayer for students before meeting with them. She also says it’s important that students see prayer as part of their coping strategy in dealing with stress.

Epp says, “We need to model for students the truth of God’s love, care and presence,” but he cautions that, while “we look to God for healing—and it’s important for us to model this—we cannot naïvely pray and [assume] the mental illness will go away.”

More on mental health:

‘Acceptance without exception’

Suicide isn’t painless

‘Poetry and art for mental health’

Resilience Road leads to mental health for women

From church to yoga studio

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.