When hymnologist Mary Oyer travelled from Uganda to Oregon to attend the 1969 Mennonite Church general assembly, she was surely filled with anticipation. She arrived in the second week of August to attend the dedication of a new denominational worship book, The Mennonite Hymnal (1969), which the General Conference Mennonite Church would also use.

As Oyer and her colleagues wondered which of these 653 songs and 98 worship resources would find resonance, a surprise lay in store. In that inaugural gathering around this collection, an unlikely standout emerged: a three-page 19th-century anthem tucked away in the “Choral Hymns” section, No. 606, “Praise God from Whom.”

“The Virginians already knew it well,” 97-year-old Oyer recalled in a recent telephone conversation. Apart from communities in the eastern United States, where the song was previously known, Oyer and her committee colleagues had presumed the song would appeal primarily to church choirs looking for a challenge.

To her surprise, its appeal as a congregational song in gatherings of predominantly white Mennonites was immediate. “In retrospect, I would say ‘no wonder,’” she added. “People at that time were ready to sing something cheerful.” It was so galvanizing in the summer of 1969, Oyer recalled. “We ended every day of meetings by singing it.”

In the 1960s, most Mennonite congregations would have been familiar with the Thomas Ken doxological text “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow” (1708), but they would have sung it with the “OLD HUNDREDTH” tune (frequently referred to as “The Doxology”) from the 1551 Genevan Psalter. This widely memorized setting served as a weekly sung benediction in the worship life of many congregations.

With the emergence of a “new” (though by 1969 well over a century old) way of singing a familiar text, worshippers would reach for a nickname to differentiate the two.

Which “Praise God from Whom”? No. 606!

When a hymn title like “Praise God from Whom” is ambiguous, often the tune name (traditionally printed in all caps) offers a path to clarity. The 1830 source material (published without attribution by the Boston Handel and Haydn Society) named this anthem simply “doxology,” which did not help differentiate it for a 20th-century Mennonite audience. The 1969 hymnal committee must have anticipated this, adding a secondary parenthetical to the tune name: doxology (dedication anthem).

The qualifier, “dedication anthem,” reveals the committee’s presumption that the song would serve as a festival hymn rather than one that would find regular use in worship.

The 1969 Mennonite Hymnal organized its contents by theme and musical idiom. White gospel hymns and choral anthems had their own sections. The next full-length denominational collection, Hymnal: A Worship Book (1992), centred the flow of worship in its theological and thematic distribution of material.

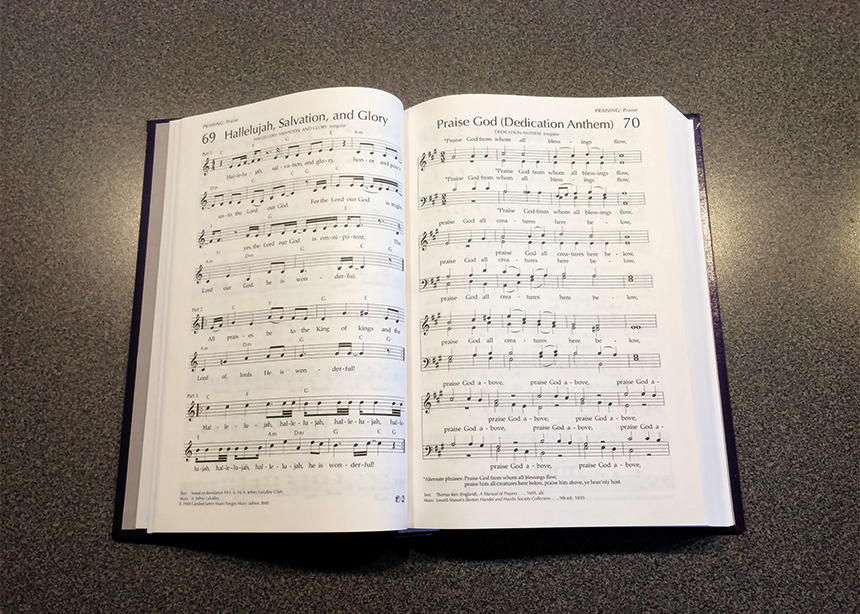

Reinforcing this flow, “Dedication Anthem,” which by then had had a 23-year history of denomination-level adoption, was promoted to a place much earlier in the collection (No. 118), reflecting its function among songs of praise.

Some communities that valued the song, however, viewed this as a demotion.

It is easy, in retrospect, to understand how a number became a de facto title. Today, though, announcing or referring to that song by its number alone divides a congregation into insiders who know some of the history behind the song and outsiders who do not—insiders who are familiar with four-part harmony and outsiders who are not.

It amounts to a cultural secret handshake. We diminish the gifts of this song if we allow it to confuse or confound.

Some urged the Mennonite Worship and Song Committee that produced the new Voices Together hymnal to correct the 1992 treatment by assigning the song its “rightful place” between 605 and 607.

Editorial judgment ultimately reasoned that backward-facing pride-of-place would diminish a potent story of the song. God’s Spirit will move in ways that we cannot expect or prescribe. Further, privileging a song so tied to white ethnic identity could serve to perpetuate insider versus outsider dynamics.

Voices Together underscores the power of this song as a praise hymn by placing it in the Praise section, at No. 70. In fact, it anchors a succession of doxologies. No. 71 is the OLD HUNDREDTH setting, which sits on a facing page with a newly composed “Alleluia” refrain (an optional tag to accompany No. 71) by Darryl Neustaedter Barg (No. 72), and a guide to signing “Alleluia” in American Sign Language (73).

Musical innovations, blurring boundaries

The placement of “Dedication Anthem” in Voices Together reflects the ways Mennonite communities are evolving, expanding and singing new songs.

The 1969 hymnbook, promoted as a conservative historical collection, landed amid a watershed moment in ecumenical church music. The committee had completed its work in 1967, and, by the time of publication in 1969, a significant renaissance of church music was underway. In his Aug. 5, 1969, review of the new hymnal in Gospel Herald, the Mennonite Church magazine, Ervin Beck noted that adopters of the hymnal might be wise to balance its conservatism (the bulk of the collection was material considered to be tried and true) with some form of more “disposable” contemporary sources.

The 1970s would indeed see Mennonites drawing on the influence of the Catholic reforms known as Vatican II, including simple choruses with guitar or piano accompaniment, and adopting songs representing greater diversities of origin. Both of these developments are explored in the 1979 Sing and Rejoice collection. The next hymnal committee (a joint effort between General Conference Mennonites, “Old” Mennonites and the Church of the Brethren) began to take shape as early as 1983.

Throughout all of this change, Mennonite worshippers have developed and maintained an appetite for exploring and adopting new songs and expressions of worship. Oyer’s study of East African songs, and the relationships she would later forge with Christian musicians across Asia, would influence the curation of Hymnal: A Worship Book. And that movement toward worshipping with a global church spread ecumenically.

The innovations in church music that were evident in the late 1960s through the ’90s continue to thrive today. We see this in a proliferation of new hymn writers, increasingly versatile contemporary worship styles and intercultural songs. Twentieth-century hymnal committees had relatively small numbers of living—or historical for that matter—Anabaptist writers to include. Those who curated Voices Together have been energized by a groundswell of Anabaptists creating art, words for worship, songs, tunes and hymn texts.

Karen Lafferty’s 1972 “Seek Ye First” (included in Sing and Rejoice and Hymnal: A Worship Book) is an example of a song from the early years of the contemporary worship movement that is still sung today. Following the risk-taking trajectories of Sing and Rejoice, Hymnal: A Worship Book and its later supplements, Voices Together included 35 songs from contemporary worship publishers. Far from being confined to the idiom’s praise-and-worship origins, these songs support a range of expression across the Voices Together table of contents.

In a recent example of how idiomatic boundaries become blurred, All Sons and Daughters, a contemporary worship band, adapted the Prayer of St. Patrick from fifth-century Ireland in their 2014 song, “Christ, Be All around Me.”

When a worshipping community adopts a new hymnal, worshippers have new opportunities to grow the ways we worship together and expand the bounds of who is invited. As styles meld over time, labels begin to hold less significance.

Not all contemporary worship music conforms to simple unison structures. Composer-songwriters like Bernadette Farrell (“Longing for Light,” 1993) occupy a musical space that ventures toward folk and popular idioms.

The accessibility of singing in unison has been important for generations. Voices Together builds on a need for balance between traditional and contemporary, unison and harmonized singing.

History and tradition are important, and must be living and flexible to maintain positive impacts.

“Dedication Anthem” does not have broad enough cultural accessibility to draw together a diverse 21st-century church. But if we’re paying attention to the gifts of “Dedication Anthem,” we will remember that the Holy Spirit will move in ways that worshippers and hymnal committees cannot predict or prescribe.

As members of Mennonite Church Canada and MC U.S.A. welcome a new denominational song collection, let’s wonder together and explore what songs and worship resources draw a diverse church together.

Bradley Kauffman served as the project director and general editor for Voices Together since the Mennonite Worship and Song Committee launched its work in the summer of 2016.

Originally published as “Make the chorus swell,” in the Nov. 27, 2020, issue of Anabaptist World. Reprinted by permission.

For discussion

1. As you think of all the church hymnals you have used, which one has had the greatest impact on you? Where/how did you and your congregation learn to sing “Praise God from Whom” (No. 606 in The Mennonite Hymnal)? How do you explain the popularity of this song among Mennonites in the late 20th century?

2. Bradley Kauffman explains that The Mennonite Hymnal (1969) had separate sections for white gospel hymns and choral anthems. What would be some reasons for organizing a hymnal this way, and why do you think later hymnals did not follow that pattern? How would you organize songs in a hymnal?

3. Kauffman comments that announcing or referring to a song by its number divides a congregation into insiders and outsiders, and becomes a “cultural secret handshake.” Do you agree? How does your congregation work at balancing music that is familiar and nurturing with songs that are less familiar but perhaps more welcoming?

4. Does your congregation sing more harmonized or unison songs? What are the benefits of each of these styles? Do you think church music is growing or declining in importance? How do you think the Voices Together hymnal will be a blessing to the church?

—By Barb Draper

Related story:

New hymnal will be ‘part of the fabric of our lives’

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.