Near the beginning of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, Frodo speaks memorable words to his fellow hobbit Sam about the adventure that lies before them: “It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.” While their odyssey was fraught with risk, the journey was well worth it, with both characters being transformed through their participation in the mission to assure that darkness did not consume their world.

Holyrood Mennonite Church in Edmonton is a multicultural congregation consisting primarily of older traditional Mennonites and younger West African immigrants. Together, we are participating in the adventure of becoming one body. The journey is never boring.

We began our common journey with no clear idea of where it might take us, yet we are finding ourselves transformed into greater Christlikeness through walking the way of reconciliation together. We are learning to integrate two very different cultural groups into one church body. There have been gifts and struggles along the way.

After worship one Sunday, a senior member of our congregation told me, “I just want you to know that I don’t like the African music. . . . I prefer the theological richness of the songs in our Mennonite hymnal.”

Immediately I tensed up, but his next words warmed my heart: “Having said that, I want you, as our pastor, to ensure that we, as a congregation, never stop singing the African songs, because it’s not just about what I want. As a multicultural congregation, we must be hospitable and make space for each other.”

Our journey began in 2001, when Holyrood sponsored four young Liberian men as refugees. Today, 40 percent of the congregation of about 100 active members, with an average Sunday worship attendance of about 70, consists of West Africans, primarily from Liberia.

Shortly after I arrived as pastor in 2006, I asked one of our Liberian members, “Why did you stay in this church once you arrived in Canada?” His answer was instructive: “We did visit other churches in Edmonton, and every church welcomed us. . . . But it went no further than that. Holyrood was the one church that invited us to use our gifts to help serve the congregation. The reason we are here is because we not only want to be welcome, we also want to participate.”

Today, we have six elders, four of whom are African. We have western and African preachers, Sunday school teachers, worship leaders and ushers. Our efforts to incorporate different peoples into one body have brought three main gifts.

Global church engagement

Embracing people of other cultures in our congregations provides a natural bridge to the wider church, something that is critical at a time of increasing nationalism. This embrace stands as a witness to the world that unity and reconciliation among diverse peoples is possible.

Through our Liberian members, we have been in partnership with two related Liberian Free Pentecostal groups since 2008. In 2010, I was honoured to be the keynote speaker at the annual national conference of the Free Pentecostal Mission of Liberia. The conference ground we met on was riddled with bullet holes, and many church members had been killed on that very land. The theme for the conference was chosen specifically in light of our partners’ new understanding of what a Mennonite speaker might have to offer: “Jesus is our peace, for he has knocked down the dividing wall between us.”

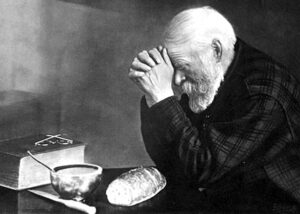

The blessings of the partnership flow both ways. Holyrood hosted two return visits from a Liberian Pentecostal pastor, and her teaching has been both inspiring and challenging, encouraging us to trust God, seek God in fasting and prayer, depend on the Holy Spirit and engage more in evangelism.

Spiritual renewal

Our African members contribute vibrancy and passion to our worship services, especially when it is the African team’s turn to lead the singing. They engage their entire bodies in worship, clapping, dancing and raising hands. Over the years, a few traditional Mennonites have learned to clap as well. Some even sway a little!

Holyrood’s African members enrich the congregation through their strong faith in God’s goodness and strength. Having survived a civil war, they display a faith that is not merely intellectual belief in the existence of God, but active trust and conviction that the God who was present in severe trial can be counted on to be present in any life situation.

To witness such faith is a blessing to those of us who have grown up in a sceptical secular society. We benefit greatly from encountering strong enthusiasm for prayer and from hearing regular testimonies about answered prayer.

In our experience, African spiritual vitality energizes a missional impulse, integrating the interior life of devotion with the exterior life of action. It is common, for example, for Holyrood’s African members to invite friends to church. At a time when many churches in the West are in numerical decline, we can learn from our global brothers and sisters’ passion for bearing verbal witness to their faith in Jesus.

Of course, learning from each other’s spiritual traditions flows in both directions. At Holyrood, many of our western members volunteer time to serve their neighbours in practical ways at the food bank, the Mennonite Central Committee thrift store, or Habitat for Humanity. We also emphasize, and seek to live out, the traditional Anabaptist values of working for peace, justice and reconciliation in our relationships.

Our African members have expressed appreciation for this Anabaptist peace emphasis, and they have shared some of it with their fellow Africans in the city.

Strengthened community life

In a world often divided along racial lines, nothing warms my heart more than to witness the genuine and mutual affection between Holyrood’s diverse members.

Our congregational life has become a school of reconciliation, in which we are all learning to respect and appreciate people who are different from us, to see the good and the potential in each other, and to recognize each other as cherished brothers and sisters in Christ. When we serve our neighbours together as a visible community, our actions are a witness that reconciliation is a reality in Jesus Christ.

Not without challenges

As enriching as our journey has been, the way has not always been smooth. No adventure worthy of the name is without challenges.

Various sources of friction include our different ways of prioritizing time, our different understandings of the relationship between money and friendship, and our divergent worship styles.

Less frequently, questions arise about theological differences. Because of these things, a few members from both sides of the congregation left and joined mono-cultural congregations.

For the large majority who have chosen to remain together, our common journey requires a good measure of humility, forbearance and generosity on all sides, as we lay aside personal preferences in favour of the common good, we are patient with each other’s strange ways, and we give each other sufficient space to express our God-given gifts.

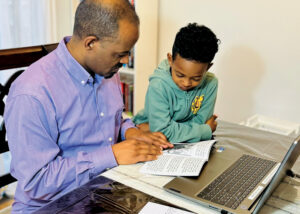

In practical terms, we have found it helpful to address our differences head on. One fall, we dedicated each week of our adult Sunday school class to comparing Canadian and West African cultures. It was the best-attended class in my years at Holyrood, a sign of our desire to know each other better.

The other significant challenge is related to power, especially with respect to how we make decisions in the congregation. In western culture, people readily think in terms of their own individual needs, and most people feel empowered to express their opinions as individuals. In West African culture, people think first in terms of the needs of the community and tend not to express individual opinions. Instead, they look to their leaders to express the voice of the community.

At Holyrood, this dynamic is most evident at our congregational meetings, which are often poorly attended by our African members, apart from a few leaders. Those Africans who are absent understand that their voice will be heard through their leaders, while the westerners wonder why so few African members are present. It is good for westerners to understand that the voice of one African leader at such meetings likely represents the voices of many others.

We are glad that God has swept us together into our shared adventure. We are being blessed, challenged and transformed by the gift of each other. We need each other, and we are learning to appreciate and depend on each other.

It is a privilege to participate together in God’s mission, to shine the light of God’s reconciling love into a world darkened by division. In an increasingly multicultural world, the future of the church is multicultural, and we are grateful to be part of it.

Werner De Jong is pastor of Holyrood Mennonite Church in Edmonton. Adapted from an article he wrote in consultation with Holyrood’s adult Sunday school class. It appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of Vision: A Journal for Church and Theology. Reprinted with permission.

For discussion

- How much cultural diversity is in your congregation? Are you comfortable worshipping with people of a different culture? What does it take to be hospitable and make space for another culture? What do you see as the blessings and challenges of cultural diversity?

- The Bible says that the church is one body with many members (Romans 12:4-8, I Corinthians 12:12-20). Do you understand these passages to mean that congregations should accommodate everyone from a different culture? Why might traditional Mennonites be hesitant to have someone from a different culture serve on their board of elders?

- If you were on the new hymnal committee, how would you choose which songs to include? Can stoic Mennonites be taught to appreciate clapping and other movements during worship? How do “traditional” Mennonites express emotion?

- When a cultural group is transplanted to Canada, what is the preferred culture of the children? What factors determine the point at which the language of the home becomes English? What do you expect to happen as our church and our world becomes more multicultural?

—By Barb Draper

Further reading:

First impressions

Exploring God’s call

Becoming Mennonite

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.