This is an unprecedented time. Unprecedented—it’s a word we’re hearing a lot in the last few months. The sense of disorientation has been palpable, from eerily empty streets to new protocols at the grocery store, an ever-increasing number of masks and people performing acrobatic feats to maintain a two-metre buffer. Somehow, this feels like a watershed moment when things have fundamentally shifted. No one knows what a “return to normal” will look like. We are experiencing an era that seems so odd, so unique, so unprecedented.

How can we find our bearings in this strange new world? Where do we turn?

While Christians often think of the Bible as a source of comfort or guidance for life—which it can be—in recent months I have been reflecting on our current situation in light of a motif that also underlies all of Christian Scripture: disorientation. When you think about it, profound disorientation may well be the most significant driving force behind the creation of the Bible in the first place—and, indeed, in the formation of the Jewish and Christian traditions themselves.

Disorientation of exile

The ancient Israelites were centred in a specific place, living a tumultuous religious life as the voice of the prophets raised repeated concerns over Baal worship and “high places.” The sacking of Jerusalem, destruction of the temple and devastation of exile shook everything up. While we may be horrified by the vitriol expressed “by the rivers of Babylon,” Psalm 137 expresses the agony and potential post-traumatic stress disorder of displaced war refugees who experienced such atrocities. The psalm also reflects profound theological disorientation, since the “songs of Zion” their captors requested from them include poetry insisting that God’s presence in Jerusalem would save it from any adversity.

Jeremiah’s call to settle in for the long haul and “seek the shalom of the city” in Babylon (Jeremiah 29) provides a direct contrast to this conviction about Jerusalem’s invincibility. In other words: don’t expect a quick rescue.

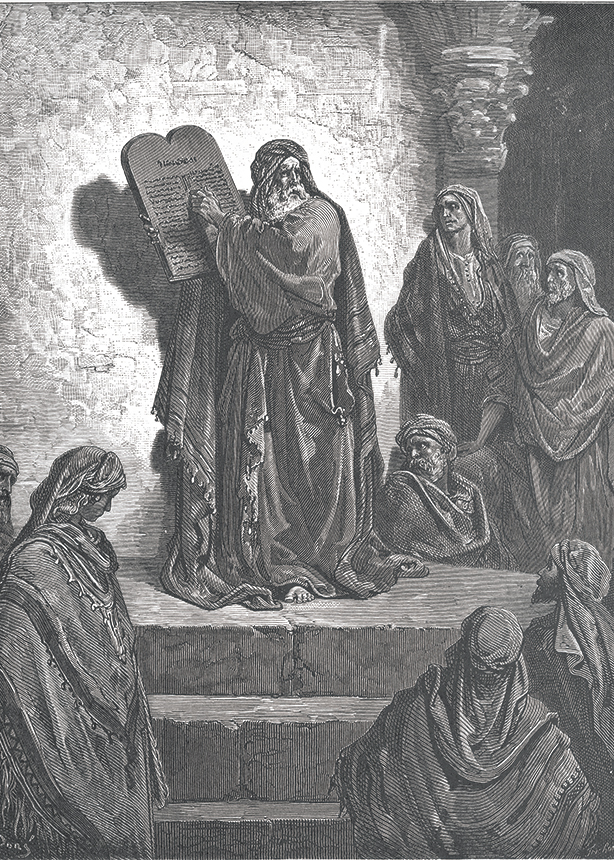

But it was precisely the experience of exile that formed Judaism. Rather than consulting prophets, after exile the community gathered their traditions and sought divine guidance by interpreting scrolls (Nehemiah 8; Daniel 9). It was their exile experience that prompted the formation of synagogues, which allowed religious communities to flourish in Babylon, Rome and Spain without a temple. And what allowed for this mobility? Synagogues centred their worship on prayer and the study of the Torah.

We Christians would do well to learn from the Jewish conviction that sees engaged Bible study, including debate and disagreement, as a form of worship.

In short, it was the disorientation and dislocation of exile that prompted a reimagined and reorganized tradition, transforming pre-exilic Israelites into post-exilic Jews.

Puzzled Jesus followers

Disruption was key for the New Testament and the development of the Christian tradition, too. During the monarchy, the term “anointed” referred to the king on the throne, but it was only after exile that the people awaited an ideal Anointed One to come (“Messiah” in Hebrew, “Christ” in Greek). Since Jerusalem was under the thumb of foreign empires, and not Davidic kings, it was only in this period of disorientation that they awaited “the return of the king.”

While we habitually read the gospels in light of an ending that we already know and expect, if we slow down we will see evidence of catastrophic disorientation throughout the New Testament itself.

How exciting it would have been to walk after the One you believed to be the legitimate heir to the throne of David, expecting him to create a kingdom of justice and peace “on earth as it is in heaven!” And how depressing it must have been to see him brutalized, tortured and killed in the most shameful way by the hated Romans. Look at the confusion and fear at the end of Mark, when people are confronted with women declaring Jesus’ tomb to be empty (Mark 16), or the initial hopelessness of those walking on the Road to Emmaus who “had hoped” (past tense) that Jesus “was the one to redeem Israel” (Luke 24:21).

Even once convinced about Jesus’ resurrection, the early church struggled when fellow followers began to die. Why is this happening when Jesus said he was coming right back (I Thessalonians)? As if this wasn’t enough, the Romans quashed the Jewish rebellion by sacking Jerusalem, destroying the temple again and scattering Jesus’ followers everywhere.

As my former advisor used to provocatively quip, “The New Testament was a huge disappointment for the early followers of Jesus, second only to his crucifixion.” Jesus’ disciples wanted a kingdom of justice and peace, but what did they get? A collection of books, a mysterious Spirit to help them understand and the encouragement to hang in there while more followers of Jesus were to be killed (Revelation 6:11). “Take up your cross and follow me” was not just a metaphor but an all-too-real possibility.

Any one of these moments could have been enough to cut off the whole tradition—the exile, a crucified Messiah, the Roman conquest of Jerusalem. But, against all odds, it survived and thrived. And it was in these darkest moments, in the midst of seemingly earth-shattering and paralyzing disorientation, that the Bible—and both Judaism and Christianity—were born.

Today

I find it painfully ironic today how often we use this Bible, born in, and a witness to, profound disorientation, to reinforce views that cannot be questioned and from which we then metaphorically throw stones at others who don’t agree with us. While some insist on the Bible’s inerrancy and historical accuracy, others use it to prompt a commitment to social justice and inclusion, which at times become a set of convictions that leave the text itself behind. Some see the Bible primarily as a resource for deeply personal, devotional faith, and are sceptical of intellectual exploration; others treat it as an analytical puzzle, kept miles away from our own context, experience or emotions.

In each case, people then tend to shy away from difficult questions or passages, even as what is deemed problematic differs. For “inerrancy folks,” recognizing diversity in the Bible can be a no-no, while those prioritizing “inclusion” often overlook Jesus’ judgment parables. In light of communal non-negotiables, people can feel unfaithful for voicing doubts, and so they keep silent, so as not to be found out or to show that they may not be as knowledgeable as the person next to them in the pew.

In other words, although specifics differ from community to community and person to person, the function of such assumptions for limiting acceptable discourse and creating relatively homogenous communities seem strikingly similar.

Right now, we stand at a pivotal moment as we are rethinking our assumptions on many fronts and adopting new practices. In this context, I encourage us to do the same with the Bible, being willing to give it another look. Rather than engaging in a perpetual tug-of-war over seeing Scripture one way or another, now may be a moment to reread it together, as a collection of documents seeking to find God working in the world in the midst of almost unimaginable disorientation.

Perhaps we have a unique, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity before us, when our current disorientation could move us to understand better the messy Scripture we have.

The Bible provides the church with a vast network of memory and reflection, a journey with many twists and turns, and so it represents an invaluable resource for living in uncertain times. Indeed, perhaps seeing our own disorientation as unprecedented says as much about a loss of our collective memory as the utter uniqueness of this particular moment. Maybe, just maybe, we have a Bible particularly suited for just such a time as this.

Now is the time to re-engage this resource uniquely equipped to help us face the unknown. My own practice includes reading a daily psalm and walking through the Book of Job. I am reading material forged in disorientation from my own unsettled place.

The Bible is a kindred spirit in the struggle to wrestle something beautiful, something meaningful, something true in the midst of trying circumstances. Lo and behold, it delivers—time and time again.

Derek Suderman is associate professor of religious studies and theological studies at Conrad Grebel University College and the University of Waterloo, Ont.

A pandemic reading list

- The Bible, in particular the Psalms, Job or Mark. For those especially adventurous, read Revelation. Read these as attempts to deal with profound disorientation and loss, not as intellectual treatises or an end-times calendar. Ease into the discomfort and struggle of these books. Ask: What kinds of disorientation does this material reflect? What other, or former, perspectives does it challenge? Where does hope lie? How does this pain resonate with today? Who experiences such disorientation? How do we respond? How should we? I highly recommend doing this reading in a group, making use of Herald Press’s Believers Church Bible Commentaries on these books.

- The Spirituality of the Psalms, or another book on the Psalms by Walter Brueggemann.

- Mark: The Way for All Nations, Willard Swartley.

- Binding the Strong Man, Ched Myers.

- On Job: God-Talk and the Suffering of the Innocent, Gustavo Gutierrez.

- At the Scent of Water: The Ground of Hope in the Book of Job, J. Gerald Janzen.

- The Lamb Christology of the Apocalypse of John, Loren Johns.

For discussion

1. How has life changed for you since February 2020? What makes you feel disoriented and off-kilter as you abide by the protocols necessary to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic? Do you think children are affected more than older adults?

2. Derek Suderman proposes that a major theme of the Bible is disorientation. What are some examples of biblical characters who felt bewildered or confused? What helped them move beyond this feeling of disorientation? What role did God play in the stories?

3. Does your family or community have stories of perseverance in the face of adversity? What role do these stories play in keeping us from being overwhelmed when life is difficult? Do you believe that facing hardships in our younger years builds resilience? At what point does suffering result in post-traumatic stress disorder?

4. Suderman suggests that we view the Bible as “a collection of documents seeking to find God working in the world in the midst of almost unimaginable disorientation.” Does this view of Scripture encourage us to express our own fears and doubts? In what ways does it deepen our hope?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.