John Enns remembers a time when 200 children filled the Sunday school classrooms at Waterloo Kitchener United Mennonite Church (WKUM).

Currently, the congregation has 225 registered members, but less than half attend. The majority are in their 70s. Enns, who chairs the vision team at the church, says most newly retired members prefer to spend their Sunday mornings elsewhere.

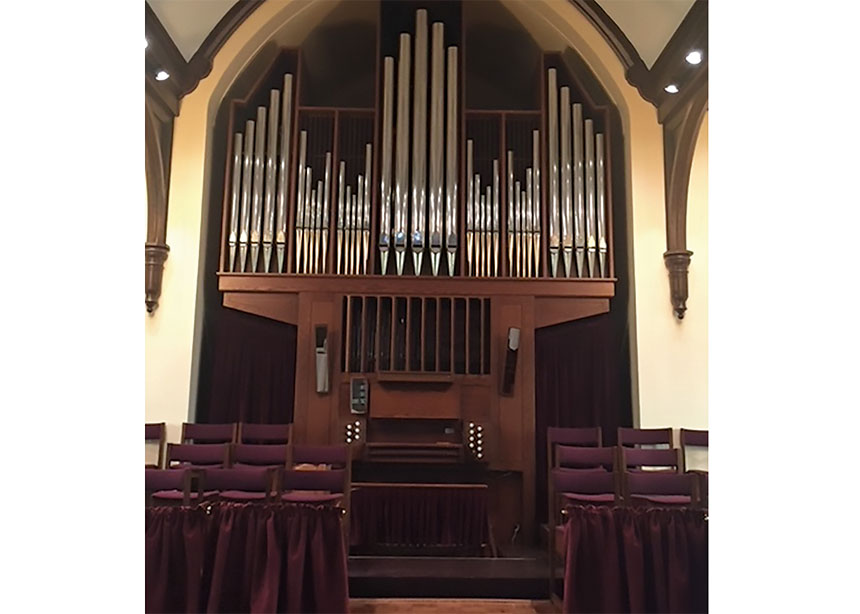

Enns’s grandfather helped found the church and looked after the construction of a pipe organ that is now the subject of some concern to the congregation as the church’s future is unclear.

Three kilometres away, the building in which Shalom Worship and Healing Centre rents space can barely contain the people or energy of the primarily Eritrean congregation, one of the newer additions to Mennonite Church Eastern Canada. The building belongs to Chin Christian Church, another MC Eastern Canada congregation, which meets there in the afternoons.

Back at WKUM, Enns says when the time comes to assist with general upkeep or repairs in their 132-year-old facility, few hands are available. The sanctuary is in use only once a week. Donations are declining.

“As I look at the statistics,” says Enns, “we probably peaked in the 1980s.” He says they could try to get back to 200 or 300 people, but “that’s not the church of the future; that’s the church of the past.”

Many Mennonite Church Canada churches across the country can surely relate to sliding numbers and the decisions they necessitate.

In B.C., Mountainview Mennonite Church in Vancouver closed in 1996 and chose to sell their building and put proceeds of the sale into an endowment fund to support future urban ministry in the region. The fund has supported a range of church initiatives, including MC B.C.’s Indigenous relations work.

The fund is largely depleted, but proceeds from the sale of another property will support initiatives of MC B.C. into the future. After spending two years considering various afforable housing options for the Peardonville property—site of the Clearbrook Mennonite Church, which disbanded in 2015—MC B.C. decided to sell the multimillion-dollar property instead. The housing projects were either too complex or did not align well with the regional church’s goals.

In small-town Saskatchewan, multimillion-dollar price tags are rare. Hanley Mennonite Church closed in 2021 but has been unable to sell its building. In the hamlet of Superb, 200 kilometres west of Saskatoon, Superb Mennonite Church has found itself in a similar scenario after holding its final service in 2020.

Back in Ontario, a June vote at WKUM resulted in 88-percent approval for selling their 15 George Street property to Beyond Housing, formerly Menno Homes.

The property has not been appraised and no dollar figures are available yet.

The current plan, though preliminary, is to demolish the church and construct a new four-storey building that will include housing, roughly 10,000 square feet of office space for Community Justice Initiatives—a non-profit focused on restorative justice programs—and worship space for WKUM. The project would take in the range of five years to complete. Apart from the church decision to sell, no decisions have been finalized.

Norm Dyck, MC Eastern Canada’s mission minister, recognizes that redevelopment of WKUM will contribute positively to the housing needs in uptown Waterloo, but he is sad to see the potential of a vibrant community hub and worship space torn down.

Before WKUM made its decision to sell, they held discussions with Dyck to explore the possibility of sharing the building with two groups looking for space.

One of them was Shalom Worship and Healing Centre. Dyck says Shalom members were prepared to explore a rent-to-own scenario in which they would have taken over maintenance and upkeep, along with related costs, while still providing space for WKUM to worship.

Markham Christian Worship Centre was also interested. This Tamil-speaking MC Eastern Canada congregation shares space with two other congregations in Markham. They have started a worship group in Kitchener and were exploring rental of the WKUM space.

“Both of these groups could have been a great fit for [WKUM],” Dyck said in an email to Canadian Mennonite.

But Enns, referring to the church’s Russian Mennonite roots, says those options did not “resonate” with the church in the same way that working with Community Justice Initiatives and Beyond Homes did. Plus, they felt the churches would have an easier time finding space than Community Justice Initiatives would.

Additionally, WKUM recognized the need for affordable housing in the vicinity of the church and felt it would be an ideal location.

Dyck says he is concerned that the narrative of the declining church has “arrested” the imaginations of some church leaders. He also notes that congregations thinking of selling may not be fully aware of how rezoning will decrease available worship space in the future.

He says local and regional governments are largely opposed to rezoning existing properties for religious activity. Once a church is gone, so are future worship options in that location.

He also notes that growing churches looking for space cannot compete with prices developers offer for properties.

Alignment

Eric Friesen sees questions of church property in light of his 30-plus years in commercial real estate, construction and property development in various provinces and abroad. He says churches considering major projects should strive to create a mission statement that aligns with their values before embarking on any construction project.

“Everybody needs to be clear on the purpose for the project,” he says. “Everything needs to be aligned.”

For congregations thinking specifically of redevelopment for housing, Friesen warns that construction of multi-residential units can become complicated quickly. In addition to various other factors, including layers of government regulation, he says the real estate and construction sectors include people who may put their personal interests ahead of the common goal.

“You need to be talking to people who are going to be working for you and not for themselves,” says Friesen. There is a lot of money to be made in redevelopment of large properties.

Friesen, who assisted with a $220,000 upgrade to the MC Canada headquarters in 2020, offers his expertise to churches looking at redevelopment, energy efficiency upgrades or total reconfiguration.

Friesen attends Foothills Mennonite Church in Calgary, and he says that, like many Mennonite Church Canada worship buildings, the Foothills building is at the age where major work—like roof repair and furnace replacement—is on the horizon.

Friesen has been in communication with MC Canada about energy audits and their implications for the long-term maintenance of church facilities. He does not want to see churches rush into decisions without full consideration of practical implications.

Setting an example

Dyck points to the Trinity Centres Foundation, a well-established Montreal-based organization that works with empty or near-empty church buildings to create community hubs in which church plants can thrive, while also providing housing and gathering space for the community.

Of the many models of church building use, three MC Eastern Canada congregations in Markham have found something that works well for them. Markham Christian Worship Centre (CWC), Hagerman Mennonite Church and Chinese Christian Mennonite Church share a building. They divide the costs of operation and maintenance. None of the groups—which range from about 40 to 70 attendees—would be able to afford the building on their own. Markham CWC’s pastor, Kapilan Savarimuthu, says total monthly contributions average about $1,000.

Hagerman and Chinese Christian worship in separate sanctuaries on Sunday mornings, while Markham CWC comes in later in the day, in addition to weekday gatherings. Hagerman’s pastor, Roberson Mbayamvula, looks after scheduling to avoid double bookings.

“It’s been really, really good,” says Savarimuthu about sharing the space with the other two groups.

He adds that all three churches focus on their goal of spreading God’s message and love of Jesus.

“When you focus on that, the small things won’t be a matter, right?”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.