Rod and Susan Reynar made a huge life change in 2014 when they moved from Alberta to Manitoba and started Emmaus House, an intentional community for university students in Winnipeg. This spring, they said goodbye to their last group of students and closed their doors.

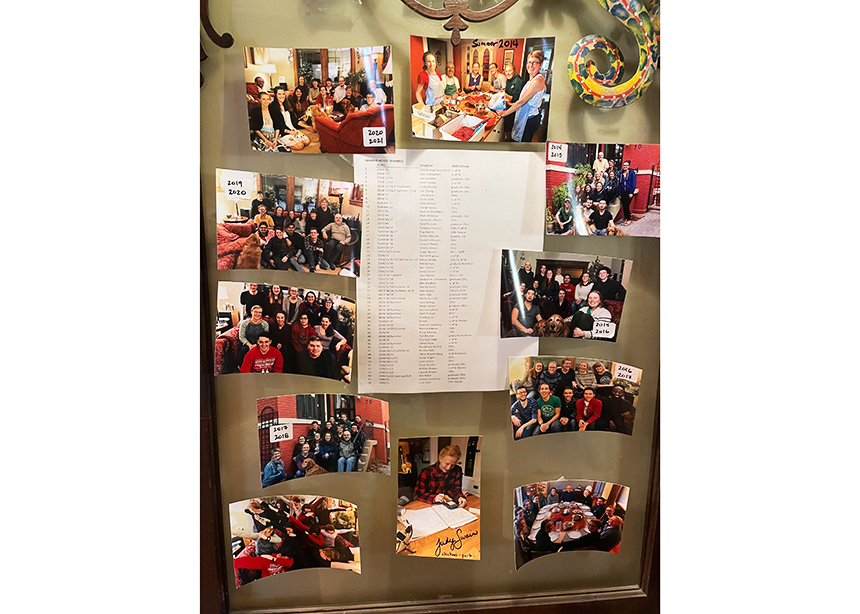

Emmaus House brought ten university students together each year from across the country and around the world. It was a place of rich conversations, shared meals and study parties. Over its eight years of operation, 56 different people lived there.

The Reynars, members of Home Street Mennonite Church in Winnipeg, developed the idea of Emmaus House when a medical procedure gave Rod a new lease on life. Rod lives with a tethered spinal cord, which he was born with, and arachnoiditis, which he developed when he was injected with toxic diagnostic dye to x-ray his spine. His arachnoiditis, severe scarring of the nerves, subjects him to high pain levels.

He’s had over a dozen major back surgeries, but it was a device he got implanted that began to manage the pain. He and Susan dreamt of what they could do with this newfound ability. Opening their home to university students seemed like a meaningful combination of Susan’s gift for hospitality and Rod’s passion for mentoring students. It worked well, offering him the opportunity to teach at CMU as a volunteer while maintaining his long-term disability support.

“We wanted this community to be a reflection of our own faith,” Susan says. “It’s important for people to know. . . we’re coming to living together in community as people who have an Anabaptist faith perspective.” But the Reynars didn’t want to be exclusionary or expect anyone to adhere to a certain list of beliefs. Their diverse community included people of other religions and atheists, people with deep faith and those with no faith background, and they welcomed conservative and progressive perspectives.

“We wanted people to know that this is a safe place to express your thoughts and your experiences with spirituality,” she says.

Emmaus House members cooked dinner in pairs and took turns cleaning the bathrooms and sweeping the floors. They walked their two dogs, biked to class, watched movies and canned salsa together.

“We wanted this to be a place where life can be experienced in an integrated way. That people could establish patterns that are healthy academically, spiritually, in their lives of service to each other and the communities in which we live, in relationship and also just in fun. How can we find quality of life in ways together that’s harder to find if we’re all navigating on our own?” says Susan.

Living well with others depends on sharing more than just the high points, Susan says. Most of life is learning to live together in the mundane. It’s these ordinary moments they cherish the most. “The highlight of the day for me was always around the table, as people blessed us with the work of their hands and took delight in sharing food,” Rod says. He misses sitting in the kitchen and always being able to count on someone coming through and stopping to talk for a while.

Living in a house with a dozen people was not always wonderful, though. “The last thing we want to do is romanticize community,” he says. “Living together with our own families is challenging, not to speak of living together with strangers. But in a world that is increasingly polarized, somehow, I think we need to push beyond that and find ways of being able to listen.”

Home is a safe place that many retreat to after tough days—which means people are not always their best selves at home. Throw in some fundamentally different perspectives and maintaining relationships can be tense. For some people, Emmaus House wasn’t the right fit and for others it was a time of incredible growth. Drafting a covenant, holding space for each other, listening with openness and committing to work through conflict—these can be hard work, but they’re all part of “developing a healthy respect for the other even if we disagree,” Rod says.

Concluding Emmaus House was an extremely difficult decision for the two. “There were far more joys and rewards than there were ever challenges, by far,” he says. But there was one problem that persisted. As Rod’s health declined, it became increasingly difficult for him to sustain the level of engagement needed to help run Emmaus House.

“This house works with both of our giftedness,” Susan says. “And when Rod’s giftedness was not able to be present because of his pain, I couldn’t make up for the things he couldn’t bring to the experience. We both have this deep desire to honour the potential in a place like this, so when we felt like we couldn’t honour that potential . . . that was hard for us to reconcile.”

The Reynars aren’t packing up and moving to a quiet bungalow for two, as many people might do after almost a decade of intense relationships and alternative living. In a way, Emmaus House isn’t really ending, but transforming. Rod’s mother, Phyllis Reynar, and Susan’s sister and brother-in-law, Tobia and George Veith, have moved into the house, creating a new intentional living arrangement for the next decade of their lives. “We learned a lot with the students . . . and we’ve benefited richly from that,” Susan says.

Rod and Susan needed more long-term stability, and it was important to them to consider family and the future in the equation. Rod’s aging mother was living on her own and feeling isolated, and they wanted to enrich her last decades. The Veiths recently returned from 30 years of ministry in China, opening the opportunity to spend time together as a family.

The couple is mindful of their children’s insecurity about the future, in the shadow of ecological crisis and economic insecurity that could mean working multiple jobs for the rest of their lives and never owning property. So, they’re laying the foundation for the option of a co-living experience for their children.

“There’s all these stresses, questions that generation is asking,” Rod says. “We could just protect ourselves and set ourselves up where we’re not participating in those questions . . . but instead wanting to walk alongside our kids and making the decision to continue in community. . . . We don’t want to abandon our kids or [their] generation.”

In Emmaus House’s early days, they had roughly 40 guests around the dinner table in a month, undoubtedly touching the lives of a multitude of people. Susan says, “Hospitality is something that is still important to this house, and we look forward to what forms that can take in the future.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.