I’m basing the form of this final missive on the last book I read, Dispatches—a harrowing and sometimes hilarious memoir by Michael Herr, who covered the insanity of the Vietnam War for Esquire magazine during two years in the late 1960s. (How insane is it that Esquire thought it needed a war correspondent in the first place?)

Most journalists, correspondents and editors I have worked with—at community newspapers in Ontario for 13 years, an international NGO, and, for the last 18 years, at Canadian Mennonite—have, at one time or another, talked of “working in the trenches.”

But what’s it like when the trenches are real?

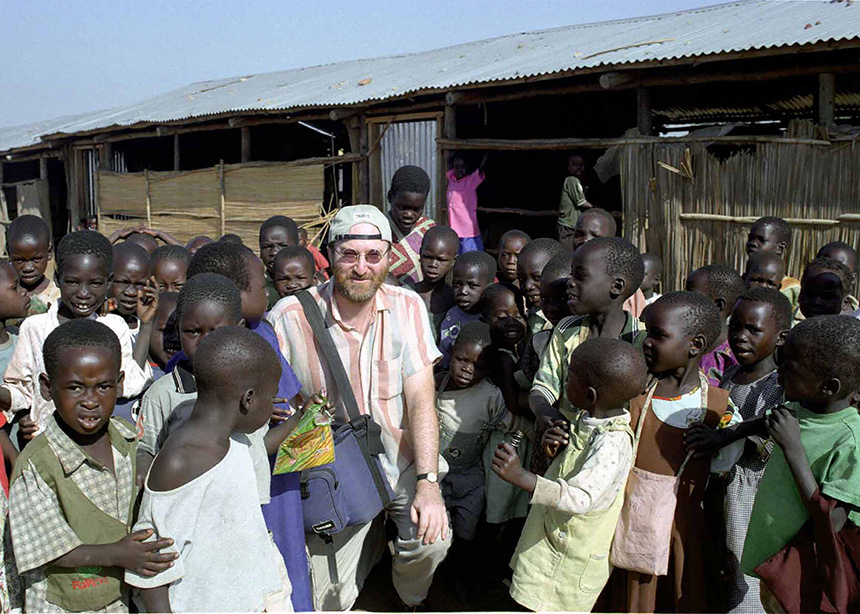

In 2004, I travelled to northern Uganda with a World Vision delegation whose goal was to help children there who were being abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in its war against the national government.

As the designated photojournalist, I found myself taking photos and interviewing former child soldiers and sex slaves a mere half-hour after landing in Gulu in northern Uganda, which was designated a war zone at that time. (In fact, one person—not from our delegation—was killed in the conflict a few kilometres away from our location, but we were never told about that until we returned to Canada.)

One incident still wakes me up at night. I interviewed a young girl, a sponsored child who had been captured by the LRA. She made a pact with another girl to escape from the camp, but that girl never showed up at the rendezvous point. So she set off running on her own, falling asleep hours later in a rut in a rural road. Fortunately, a truck full of soldiers patrolling the area saw her lying there and took her to the war-child rehab centre in Gulu.

Knowing what would have happened to her if she had been recaptured by the LRA—death by a thousand cuts at the hands of other children her age—I asked her why she would take such a risk.

“I’d reached a point in my life that I was ready to die.” That’s all she said. And the interview continued along happier lines.

It wasn’t until I was transcribing my notes onto a dinky laptop in an air-conditioned hotel room back in Kampala (imagine the opening scene of Apocalypse Now) that the full force of her words got to me. I remember looking out the hotel window and the clock across the street said two o’clock. At five o’clock, a colleague knocked on my door to tell me it was suppertime.

I woke up with a start, staring at the screen with those 13 words on it (the last words I had typed three hours ago). I was soaking with sweat, and, in the mirror, a whiter shade of pale reflection looked back at me. I took a shower and offered my apologies for being late to dinner.

That night, I called home and told my son to thank God that he was born in Canada. I didn’t tell him why.

To this day, I am still processing those three weeks. I have framed a number of my photos from that trip (including the one on the cover) and they still hang on my walls at work and at home. But not one of the girl who “was ready to die.”

Is journalism next to godliness?

Early on in my journalism career—pre-Canadian Mennonite—I attended a Word Guild event in Guelph, Ont., where the topic of “What are the godly character traits of a journalist?” came up at the dinner table.

After “gentle Jesus meek and mild” suggestions were bandied about, I went out on a limb: “What if journalists, like God, were no respecters of persons?” (Romans 2:11, paraphrase). After all, the same Jesus who told Peter that the keys of heaven were his, then told him to “get behind me Satan”; he cured both rich and poor alike; and he managed to offend religious and political leaders, as well as the common people, to the point where they all wanted him dead.

The reaction I got at that event was the same as when I’d tell people that the motto of the first newspaper I ever worked for, the Manitoulin Expositor, was: “Who dares not offend, cannot be honest.”

Not surprising, that offends some people. Like a couple of fully patched members of the Hell’s Angels who read the logo on the back of my Expositor sweatshirt at a blues festival in 1988. They hauled me off the grass and told me I’d offended them.

I told them sincerely that that was not my intention. I don’t remember my exact words, but I said something to the effect that not respecting the status of a person or institution—or daring to offend them—is exactly what journalists need to do if that’s what it takes to get to the bottom of a news story.

“You mean like ‘sticking it to the man?’ ” one of them said.

“Yeah. When it’s necessary,” I answered, glad that they understood my intent.

After conferring with each other, they told me I was good to go. Relieved that the encounter was over, I went back to “grooving” to Savoy Brown with the rest of the crowd.

Rick McCutcheon, emeritus publisher of The Expositor, who gave me, and many others like me, the opportunity to learn the news business from the ground up, once told his editorial staff that one way to tell if you did a really good job on a contentious article, was if the people quoted in the story all came away a little uneasy. If one, or both, sides liked what was printed too much, he said they probably thought they had gotten away with something. We weren’t supposed to let them think that.

Three CM stories that caused offence

- “Recipe for relief”

A mennopix digital art version of ‘Recipe for relief: Homage to andy warhol’ by Ross W. Muir

The first photo essay I did just a few months into my time at Canadian Mennonite started out benignly enough. The two-page spread, a pictorial of Mennonite Central Committee’s beef-canning operation at the University of Guelph, Ont., featured photos of sides of beef being sliced and diced, then cooked, canned and labelled.

What I didn’t know was that a CM staff member at the time was a vegetarian, who found the photos disturbing, to say the least. I think I apologized (I hope I did), but I still think that a weeklong project involving 400 volunteers canning 21,000 or so cans of meat for distribution to starving people around the world was newsworthy.

For our non-meat-eating readers, I’m glad that, in recent years, CM has been able to cover the work of the Ontario Christian Gleaners, whose volunteers produce millions of dried vegetable soup packets, along with other food products, for the same worthy cause each year.

“Say no to the logo” front cover

“Say no to the logo” front cover

Back in 2011, the new Winnipeg Jets hockey team got a new logo that featured a fighter jet insignia. In the Oct. 3 issue, we ran a two-part feature, one part asking, “Should Mennos cheer for fighter Jets?” and the other claiming, “New logo a distraction to talking about peace and violence.”

Dan Johnson, our graphic designer at the time, and I worked on the cover, which is more strident than the two inside pieces. We wanted to catch people’s attention and draw them into the feature. It worked, but in ways we didn’t expect. For some reason, we thought the declaration was self-evident for our Mennonite readers.

Wrong. We offended both Jets’ fans and others who just didn’t like to be told what to believe or do.

According to some, even our board chair at the time got it wrong, when she said, “Of course, they should say no.”

- Numerous stories of pastoral misconduct

Having covered the crime and court beats for The Expositor for 11 years, and winning feature-writing and community-service awards from the Ontario Community Newspapers Association in 1997 for a three-part, eight-story series called “The public perception of guilt and innocence,” it mostly fell to me to continue this at CM.

This time, I knew to expect two equal and opposite complaints: One side wonders why such stories need to be dragged in front of readers (especially if the accused is dead), while the other has serious trouble with the word “alleged.”

Because the press has to follow the libel laws of the land, pastors (and others) are presumed innocent in the law courts until proven guilty, unlike church tribunals, including Mennonite Church Canada, that use the concept of “preponderance of evidence,” or other similar language, to decide on guilt or innocence.

I remember one pastoral misconduct story that was initially submitted by a correspondent, in which a pastor faced criminal charges. But the church had jumped ahead of the slow-moving legal process and was working to restore him in the eyes of God and the church. I can’t remember the verbal gymnastics we went through to portray both realities without libelling the accused, but we did it.

And since the #MeToo movement made headlines in late 2017, journalists have faced being called out for not being “allies” of those making “allegations.” Even before the movement, I always maintained that journalists writing news—crime or otherwise—don’t have the luxury of being allies or taking sides. If you want to do that, write an op-ed or wave a banner.

Final dispatch for CM correspondents past and present

Like Herr and a couple of his media buddies, who were chewed out by an army commander for not saluting an officer upon returning to base, our staff writers and photographers can proudly declare to those whose lives and work they cover, “We don’t salute either. We’re correspondents.”

The full version of this article appears in the May 5, 2023 print edition of Canadian Mennonite.

*Updated May 26, 2023

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.