Update: In October 2020, Mennonite Church Eastern Canada announced the termination of the ministerial credentials of John D. Rempel, on the basis of ministerial sexual misconduct. To learn more, see ‘Credentials terminated for theologian-academic-pastor.’

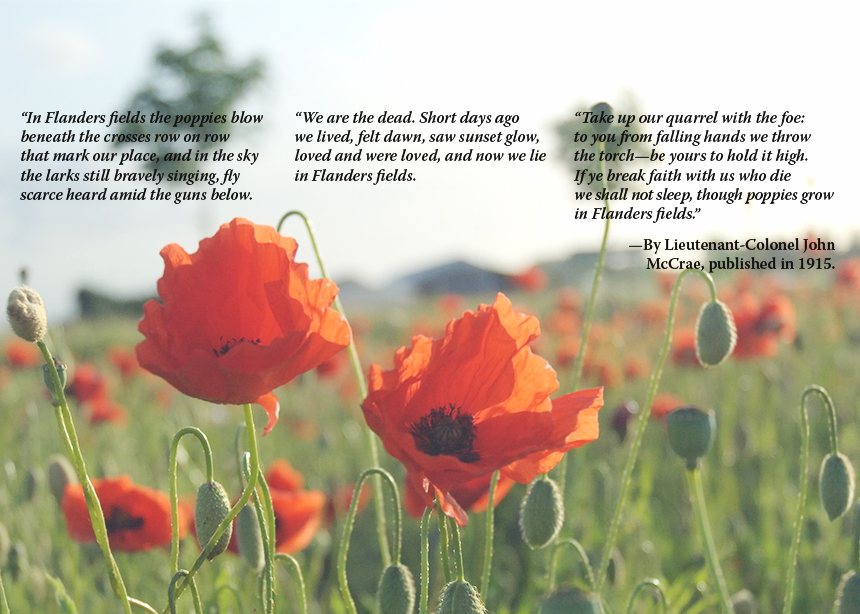

How do we “take up our quarrel with the foe”? What does it mean to “break faith with those who die”? Those are the questions before us, especially on a Peace Sunday.

John McCrae’s poem is at once tender and passionate as he mourns the hundreds of thousands of grave markers of soldiers killed in the First World War. For McCrae, taking up their quarrel with the foe meant to defeat by military might those who threaten our way of life. For him, breaking faith with those who died meant to fight to the last man to destroy the enemy to the last man. We respect soldiers who suffered, yet we cannot remain silent about going to war: It is the greatest scourge on earth, the overwhelming folly of humanity, the ultimate outworking of Original Sin.

If we are true to the spirit of Jesus, we will not want to escape the hardships soldiers endure. We will also want to “take up the quarrel with the foe,” which is hatred, bigotry and oppression. The question is, How do we do that? We, too, do not want to “break faith with those who die.” We are called to make sacrifices for justice, freedom and equality. The burning question is, How do we do that?

To address the question, we have to start with our estrangement from one another and from God.

Christ broke down the wall of hostility

In Ephesians 2:12-19, Paul is writing to a congregation made up of Jews and gentiles who confess Jesus as the Messiah. He reminds the gentiles that at one time they were without Christ, alienated from his people and strangers to the covenant (2:12).

On the cross, Christ broke down the wall of hostility between enemy camps in order to create a new humanity. On the cross, God started over again with creation by fashioning a new community of former enemies, like Jews and gentiles.

Think of the wall that ran through Berlin and the one that now runs through Palestine. In his death, Christ broke down such a wall. He pried loose the grip of evil on humanity so that evil can no longer compel us to hate. A new humanity that we are part of is gathering where the wall once stood; it is the church, the place where God is visibly at work reconciling enemies. At the same time, God’s embrace is not confined to the church: Wherever forgiveness is offered, wherever love is attempted, God is at work.

The most important aspect of peacemaking is that God has made the first move. We cannot break the vicious circle of violence ourselves. In the life, death and resurrection of Jesus, God has broken the power of evil to compel us to do evil. We become peacemakers, not in our own strength, but in God’s.

Paul reminded the Christians in Rome of this: While we were weak, while we were sinners, while we were still God’s enemies, Christ died for us (Romans 5:6-10). In other words, it was God who took the first step to overcome our alienation from him and one another. We can love others only because God first loved us.

God’s love makes our love possible

Luke 6:27-32 needs to be read and obeyed in light of God’s love making our love possible. Earlier in this account, Jesus had just blessed the poor, the hungry and those who were reviled because they are followers of Jesus.

This is his breathtaking message: Love as God loves. God loved us, the church, while we were still his enemies. That is what he asks of us now in his most awesome commandment, his hardest saying. Only someone whose heart has been disarmed can begin this apprenticeship as a reconciler.

We—and I include myself—find it irresistible to blunt the sharpness of Jesus’ challenge. We can barely muster the courage to love people who love us. Could God expect more than that? “Yes!” Jesus answers. He goes on to explain why: “If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you?” (6:32) In other words, if you want to love without taking risks, you love only to the extent that someone loves you. Acting that way follows from the fear that there will not be enough love to go around.

Lines from Enchanted April, a movie I once saw about two women in loveless marriages, still haunt me. Rose and Lottie go on a trip together to try to figure out what went wrong. Suddenly Rose has a moment of truth. “I loved my husband legally,” she confesses. “I refused to love him an inch more than he loved me. And he did the same to me.”

Risking love when you have no assurance that it will be reciprocated is possible only if you believe, through Christ, that there will be enough love to go around. This is an overwhelming thought: To love someone who hates you or curses you, especially for people who know what it is like to be persecuted and tortured.

No matter how many times we hear this summons, it overwhelms us.

The example of Michael Sharp

Now let’s apply the command to love our enemies beyond personal relationships, to political ones. In early 2017, a Congolese rebel group kidnapped and killed Michael Sharp, an American Mennonite and a United Nations investigator of inter-tribal violence in the Congo.

The Washington Post said the following about Sharp: “He had impressed many with his cultivation of trust among eastern Congo’s rebel leaders in his three years there with Mennonite Central Committee.”

Sharp and a Swedish colleague risked loving soldiers who had raped and pillaged. From earlier conversations, Sharp and his colleague took a chance on desperate people they believed were war weary enough that they might risk peace negotiations with their tribal enemies. They weren’t, heartbreakingly enough.

Yet listen to what John Sharp, Michael’s father, said sometime after his son’s funeral: “We teach that violence solves nothing, as history proves. My son’s death should not be an excuse to cut and run from the Congo.”

The hard fact, the brutal fact, is that Michael Sharp and his colleague were killed. They died refusing to hate or give up on those who hated them. Perhaps it was an act of God’s providence that something about Michael’s tragic story captivated a reporter in the second-most prominent American newspaper. And, because of that, hundreds of thousands of people have heard about a man with a disarmed heart, who risked entrusting himself to those who hated him, who did so because he knew that the wall that divides people into enemy factions had already been broken down. That is how we “take up our quarrel with the foe,” how we keep from breaking faith with those who die.

Back to the source of nonviolence

Entering the world nonviolently calls for us to be wise as serpents and innocent as doves. I don’t look down on peace and conflict studies or the complicated dynamics of getting foes to the negotiating table. But, by themselves, these processes can put the whole weight of peacemaking on technique. So it seems urgent to me on Peace Sunday to go back to the source of nonviolence. That is the boundless love of God, who in Christ took on our flesh, who died with us and for us, while we were still God’s enemies.

Once we enter the lifelong apprenticeship of learning to trust that we will not be abandoned by God, ever, in any circumstance, and once we trust that the embrace of divine love on our life is for keeps, then we are on the path of overcoming evil with good, of dislodging curses with blessings.

If we are willing, like Michael Sharp was, to spend our life knowing that we can’t ever lose it, then we are set free from fear, set free to love without boundaries on whom we love.

John D. Rempel is a Senior Fellow at the Toronto Mennonite Theological Centre. This reflection is adapted from a Peace Sunday sermon he preached at Grace Mennonite Church, St. Catharines, Ont., on Nov. 12, 2017.

For discussion

1. What memories or associations pop into your mind when you hear the poem “In Flanders Fields”? What is the central message of this poem? How should followers of Jesus respond to this message?

2. John D. Rempel reminds us that “Christ broke down the wall of hostility between enemy camps.” What are some examples of modern walls that serve to maintain hostility? How can the church help to break down these walls and to reconcile enemies?

3. Rempel says, “We are called to make sacrifices for justice, freedom and equality.” Can you think of examples of people who have done this? Why is it so challenging to risk love without the assurance that it will be reciprocated?

4. What can we learn from the story of Michael Sharp? What did Sharp’s father mean when he said his son’s death is no excuse to “cut and run from the Congo”?

5. How do you respond to Rempel’s idea that to “take up our quarrel with the foe” is to fight hatred, bigotry and oppression, and to overcome evil with good?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.