WARNING: This story contains graphic descriptions of violence.

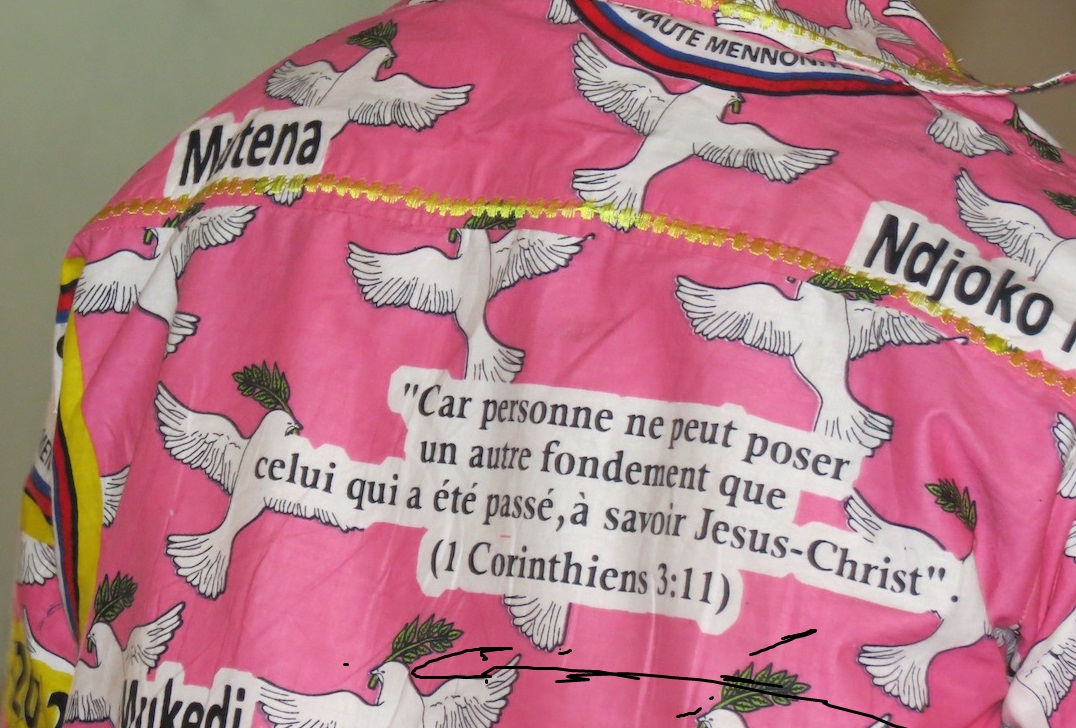

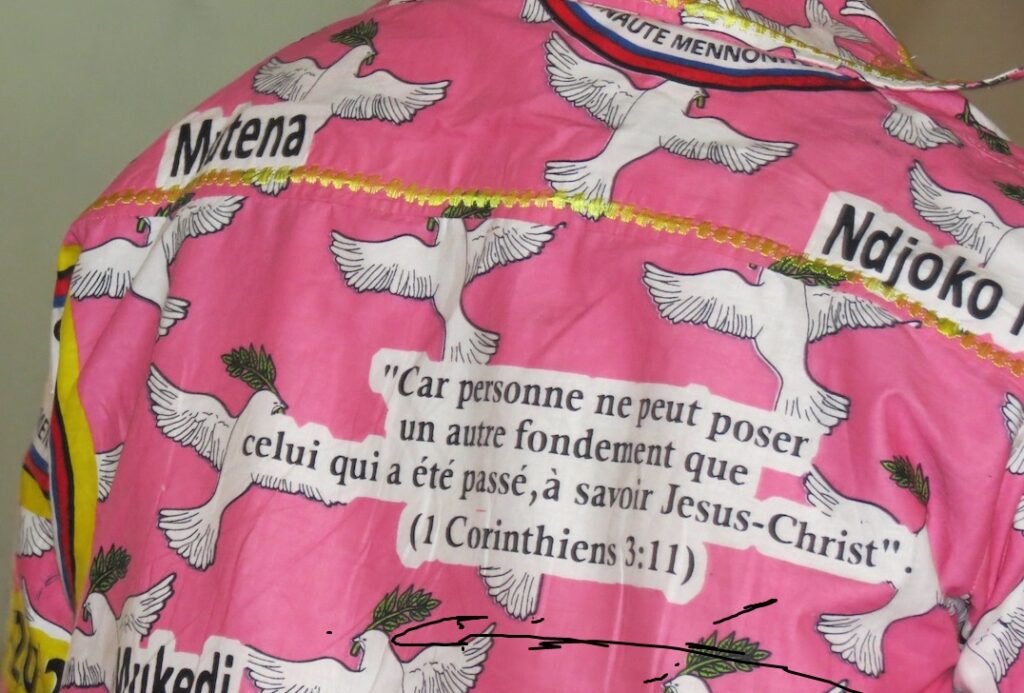

Dozens of Congolese Mennonites have been killed, hundreds of their homes have been burned, and thousands of them have fled, as violence consumes the Kasai region, birthplace of the Mennonite church in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) reports 36 confirmed deaths of Mennonites, 12 church schools destroyed or attacked, 16 churches destroyed or attacked, and 342 homes destroyed. Those numbers may rise in the coming days.

Speaking through a translator via Skype, Pastor Adolphe Komuesa Kalunga—head of the Mennonite Church of Congo as well as an elected member of the government of President Joseph Kabila—emphasized that it is difficult for church leaders to communicate with people in the Kasai region because many are in hiding in the forests.

Those Mennonites are among an estimated 1.4 million displaced people in the region, including roughly 850,000 children. The death toll is more than 3,000.

The violence started last year with tension between the government and a chief in Tshimbulu, a town in a region considered opposed to the government. After being sidelined by the government, the chief, who carried the traditional title Kamuina Nsapu, formed a rebel militia that destroyed a local government post. Government forces then killed him and refused to return his body.

The chief’s militia, also under the name Kamuina Nsapu, then grew, fuelled by unequal distribution of wealth, disenfranchisement and adherence to a particular deity that rebel leaders claimed would render fighters invincible.

Government forces responded by reportedly killing indiscriminately door to door in areas associated with the rebels. This spring, as hostilities continued, a second particularly brutal militia—Bana Mura—was formed with participation of elements of the government, according to the UN. Much of the violence fell along ethnic lines, with all sides reportedly guilty of atrocities. Entire villages were destroyed on the basis of ethnicity.

Gruesome accounts

A Mennonite assessment team made up of Congolese church people heard stories of mutilations, beheadings and sexual violence. The team met with a range of survivors, including some Mennonites, in Tshikapa and Kikwit.

Rod Hollinger-Janzen, executive coordinator of African Inter-Mennonite Mission (AIMM), which has been involved in the region since 1912, visited Congo in July 2017. He spoke with Joseph Nkongolo, a member of the assessment team. Nkongolo recounted the story of a mother handing a newborn baby to her six-year-old daughter before being killed along with her husband. The rebels then sent the girl away with the baby.

Another woman witnessed her husband’s decapitation and was then forced to carry his head to a sort of altar used by the killers. Hollinger-Janzen saw pictures of heads gathered around an idol-like figure.

Children witnessed their parents being hacked to death with machetes.

Roughly a third of the people the assessment team spoke with were too traumatized to even say whether their greatest need was water, food or clothing. Some families were eating only one meal a day.

While Nkongolo appeared “shattered” by what he witnessed, Hollinger-Janzen expressed deep admiration for the strength of the assessment team members. “They are carrying the pain of so many people.”

Earlier this summer, Hollinger-Janzen learned via an email from Adolphine Tshiama, president of the women’s organization of the Mennonite Church of Congo, that her brother and several of his family members had been killed by the Bana Mura militia in two separate attacks. On Aug. 6, her sister-in-law, niece and three of her niece’s children—all thought to be dead—miraculously showed up after hiding in the forest for nearly three months.

Tshiama was unavailable for an interview due to illness.

At the Kalonda Bible Institute, several kilometres outside Tshikapa, the army moved onto the mission compound next to the school. Amid severe tension, the school relocated to a church compound in Tshikapa, where graduation was held in July.

Cursed with wealth

The history of Congo, formerly Zaire, is drenched in violence and exploitation. The second-largest country in Africa, it gained independence from Belgium’s oppressive control in 1960. Four years later, Mobutu Sese Seku seized power in a coup, beginning 32 notoriously ruthless years in power. With massive mineral wealth generated in the country, he reportedly embezzled billions of dollars while enjoying American support.

In 1994, following the Hutu-led genocide in neighbouring Rwanda, Mobutu sided with Hutus who fled to Congo and wanted to attack Tutsis in the country. That mushroomed into a war that cost five million lives. In 1997, Mobutu was replaced by Laurent-Desire Kabila, whose son Joseph is now president.

Despite vast mineral deposits, Congo ranks 176 out of 188 countries on the UN Human Development Index. Kasai is a particularly poor region.

Although the constitution required the younger Kabila to step down when his second eight-year term ended in 2016, he has delayed a vote, saying the government cannot afford the required voter-registration process.

As reported by The Guardian newspaper, polls indicate Kabila would lose badly if elections were held now. He, along with his family, reportedly control an extensive network of business interests in the country. This all contributes to instability and foment, especially in impoverished opposition areas.

Some have suggested the killing of Kamuina Nsapu was intended to create chaos that would further delay an election.

Mennonites in the middle

Congo is home to more than 235,000 Mennonites in three main groups: Mennonite Church of Congo, a the Mennonite Brethren Church of the Congo and the Evangelical Mennonite Church of Congo. Only the U.S., Ethiopia and India have more Anabaptists.

Dozens of Mennonite churches lie within the Kasai conflict area. The Mennonite Church of Congo—the main Anabaptist denomination represented in the Kasai region—reported 19 districts, each with five to eight congregations, directly affected by the violence.

Mennonites not directly affected are working to address the needs. Families—many very poor themselves— are hosting displaced people; congregations are collecting aid; and the churches are collaborating with MCC, AIMM and other agencies in a broader response.

The response will be focussed in Kikwit and Tshikapa, the largest destination for displaced people, and home to about 25 Mennonite churches.

Some people have fled to Angola, where Mennonites are involved in hosting refugees, according to Mennonite World Conference.

Bruce Guenther, head of disaster response for MCC, said it is “alarming” to see how few aid agencies are involved in the Kasai region. MCC is proceeding “urgently and carefully” in collaboration with numerous organizations and churches on the ground in affected areas. He says MCC wants to “accompany the local church to respond as they see fit.”

Komuesa said the five priority needs at this point are food, healthcare, housing (especially with the rainy season approaching), schooling and reconciliation. While some sources indicate the ethnically charged conflict has tested the unity within the Mennonite church—which includes numerous ethnic groups which split along ethnic lines in the 1960s—he said harmony still exists within the church. “We need to reach out,” he said, “and share the peace and reconciliation that we have with other people.”

Mulanda Jimmy Juma, the MCC country representative for Congo, said via phone that reconciliation starts with the aid response. The goal will be to get people of different ethnic groups working side by side to deliver aid to diverse recipients. With considerable peacebuilding experience in various parts of Africa, he also spoke of the value of bringing children from different groups together, partly because when parents see diverse children playing together it helps change their perspectives.

Komuesa said the situation is gradually getting better, with tensions subsiding. As a pastor and government official, his message to the militias is to stop using violence. He said the role of government is to protect the population and restore security.

Inner plea

Hollinger-Janzen emphasized the amount of stress many Congolese live with. The majority of people struggle daily to feed their families. Add to that, he said, a legacy of colonial oppressions, western interference and a corrupt state system has never worked for the people. Then add a spark of violence.

“I try to think my way into that and imagine what it is like,” he said.

Grappling with the immensity of the situation, he said, “I want to believe that the God we worship can come to anyone in any situation . . . that somehow God’s love can be communicated no matter what.”

He encouraged people to support MCC’s Kasai Response—among the organization’s other worthy causes—as a concrete expression of love. “Now is the time to respond,” he said. “This is why we are believers. This is what Jesus calls us to.”

Like Juma and Komuesa, he emphasized prayer as the primary response, “trying in some way to enter into what it would be like for people to live in this situation.”

“Let’s deepen our compassion,” Hollinger-Janzen concluded. And when we do not know what to pray, “the Spirit prays within us.”

To donate, see mcccanada.ca.

—Corrected Aug. 22, 2017

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.