Recently, I read a book that unsettled my sense of hope.

In her memoir I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, Austin Channing Brown, a racial-justice leader, writes about growing up Black, Christian and female, and her journey to self-worth while navigating America’s racial divide. In the final chapter, “Standing in the Shadow of Hope,” she says, “[T]alking about race in America is not usually a hopeful experience if you’re Black. . . . The persistence of racism in America—individual and societal—is altogether overwhelming. It doesn’t lay the fertilizer for hope to grow. And so hope for me has died one thousand deaths.”

I have to admit, I don’t really know what it feels like to have hope die over and over again.

My sense of hope has generally been positive and optimistic, associated with faith that God’s love is stronger than any other force and that, in the end, love wins. It is based on the assumption that humanity is essentially good, and when we make God’s love real in the world, we keep hope alive.

My sense of hope has also been shaped by the season of Advent—by the sense of longing and anticipation that God’s love can be born among us again, as it was in Jesus. Hope conjures up soft warm images of candles and the haunting harmonies of “O Little Town of Bethlehem” on Christmas Eve, when we sing with hearts full of assurance: “Yet in thy dark streets shineth the everlasting light / the hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight.”

Hope has to do with seeing things that are not quite there. It has to do with anticipation and expectation, with wants and desires and dreams. Hope calls for trust and courage and imagination. Biblical hope is the confident expectation that God will fulfil what God has promised, because God is faithful.

Advent is a season of hope—of waiting in anticipation for God’s promise to be fulfilled. Of course, during Advent we acknowledge the shadows, we sit with the world’s suffering, with our longings for peace and justice, and we wait. But like the glow of the Advent candles, our hope persists. It flickers sometimes, but it survives, born anew at Christmas.

Channing Brown is calling me to sit with hope differently this Christmas season. She invites me to ponder the fragile nature of hope and what it means when hope dies.

I appreciate that hope can sound too rosy, optimistic and unrealistic sometimes. It can be an empty platitude that ends up seeming false and naive. We also know that hope can be manipulated and exploited, when people make promises they cannot keep, or prey on the doubts and fears of others. Hope can be a mirage—just wishful thinking that disappears when we get close. Hope dashed can lead to crushing disappointment and deep frustration that is not good for our well-being. Hope can even lead to complacency; it can be lazy. It can create an illusion of comfort that everything will be okay, which actually leads to inaction.

When hope dies

In her memoir, Channing Brown recounts many ways that hope has let her down.

“Each death of hope has been painful and costly,” she writes. But she has “learned not to fear the death of hope,” for that is what “comes with living, with struggling, with believing in the possibility of change.”

She describes how “the death of hope gives way to a sadness that heals, to anger that inspires, to a wisdom that empowers me the next time I get to work, pick up my pen, join a march, tell my story.” In the mourning after each death of hope “there always arises a new clarity about the world, about the church, about myself, about God. And in this there is new life. Realignment. Rediscovery. And on the really good days: renewal.”

She asks, “What is left when hope is gone? What is left when the source of my hope has failed?” That is when she says, “I have learned to rest in the shadow of hope.”

Channing Brown writes, “I do not believe that I or my children or my grandchildren will live in an America that has achieved racial equality.” But living in the shadow of hope means “knowing that we may never see the realization of our dreams, and yet still showing up . . . work[ing] toward a world unseen, currently unimaginable. . . it is working in the dark, not knowing if anything I do will ever make a difference. It is speaking anyway, writing anyway, loving anyway. It is enduring disappointment and then getting back to work . . . it is pushing back, even though my words will never be big enough, powerful enough, weighty enough to change everything. It is knowing that God is God and I am not.”

Another writer and activist, Mary Jo Leddy, recalls a story in her book Radical Gratitude that also explores the weak and limited nature of hope. While keeping vigil at the bedside of “a holy older woman” who lay dying, Leddy recalls that the unconscious woman suddenly awoke to recount a dream: “I had a dream. I dreamt that all the men and women were all seated around a round table, all equal, all free. It will take a thousand years but it doesn’t really matter, because it’s going to happen.”

Leddy admits that “it is sometimes difficult to hear that ‘it will take a thousand years,’ but it makes all the difference in the world whether we believe in the power of this dream to prevail. It is this dream that has the power to sustain us in struggle and the power to endure through the collapse of our particular hopes.”

Martin Luther King Jr. also knew what it meant to live in the shadow of hope. In his last speech, given the night before he was assassinated, he spoke these words: “We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter to me now because I have been to the mountaintop. . . . I have looked over and I have seen the promised land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the Promised Land.”

Resting in the shadow of hope

My challenge this Christmas, as a person of relative privilege, is to listen to those who rest in the shadow of hope. They are teaching me that hope is sustained by practise—by exercising it like a muscle. Hope is a refusal to accept the world as it is. Hope is about making the commitment to God’s love and justice, and showing up day after day to make them real, despite the consequences, the losses, the frustrations and the broken promises, even if it takes a thousand years.

Leddy reminds us that Jesus “lived with a sense of meaning and purpose in the most chaotic and oppressive time.” He lived with God “as the point of his being. . . . He knew who he was, that his deepest identity lay in the mystery that he was born of God. And he knew that he was ‘for’ God, that he had come to announce the great dream of God,” she writes. “Jesus has left us with this vision, a vision worthy enough to summon every aspect of our being and the whole of our lives.”

Those who rest in the shadow of hope also teach me something about the fragile nature of hope. It resonates with biblical themes of the unlikely choice and the upside-down nature of the kingdom Jesus called his disciples to form. God often works through those who are perceived to be inadequate and improbable for the job. Jesus’ life and teachings turn upside down our assumptions about who is most capable and worthy. In facing his own limitations, the Apostle Paul is reminded by God: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (II Corinthians 12:9).

Hope is a weak and improbable player. But, according to the biblical story, the fragile nature of hope is its strength. This is especially true when we consider the fragile nature of a baby, born to poor parents, in an animal stable, in a homeland under occupation, as Luke tells it in his gospel. So much can go wrong here. Hope can die. Jesus can be killed. And yet, despite the unlikely circumstances, wise elders like Elizabeth, Simeon and Anna recognize Jesus as Lord, as the fulfilment of God’s promise, as the one to bring salvation and redemption, even if they are too old to witness his ministry fully unfold.

So what is left when hope dies? Channing Brown writes: “I let the limitations of hope settle over me. I possess not the strength of hope but its weakness, its fragility, its ability to die. . . so I abide in the shadows, and let hope have its day and its death. It is my duty to live anyway.”

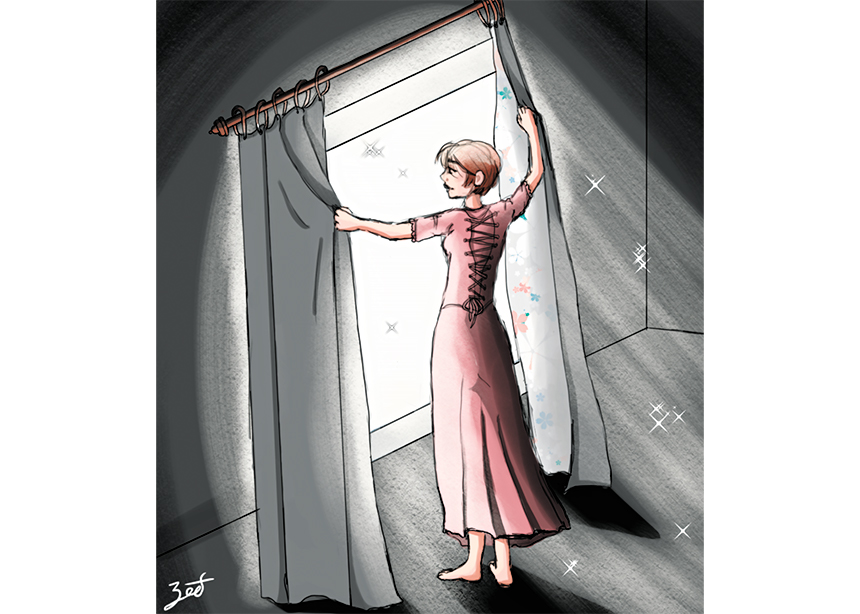

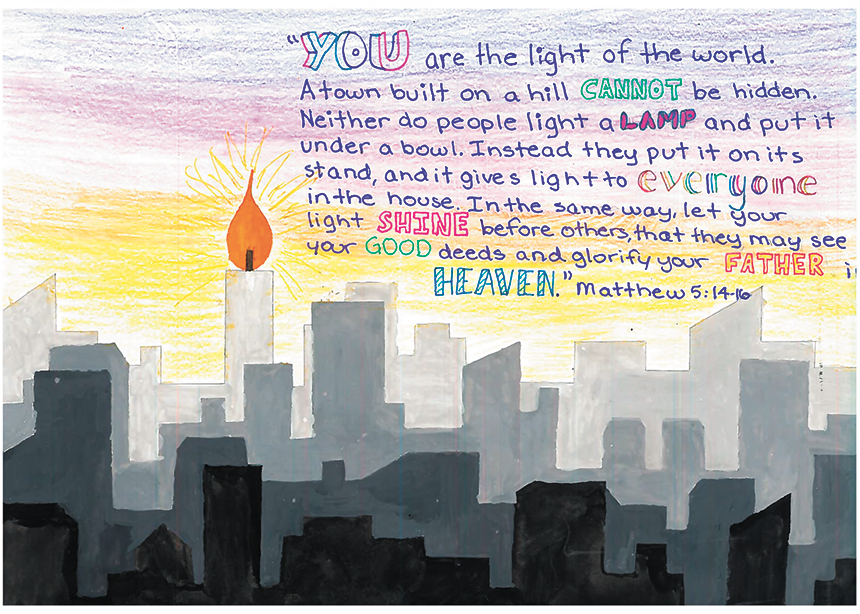

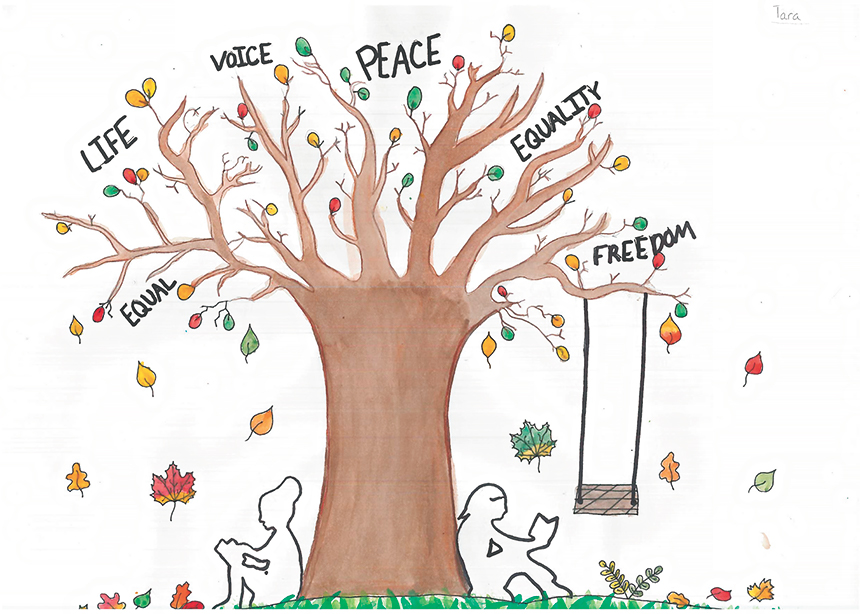

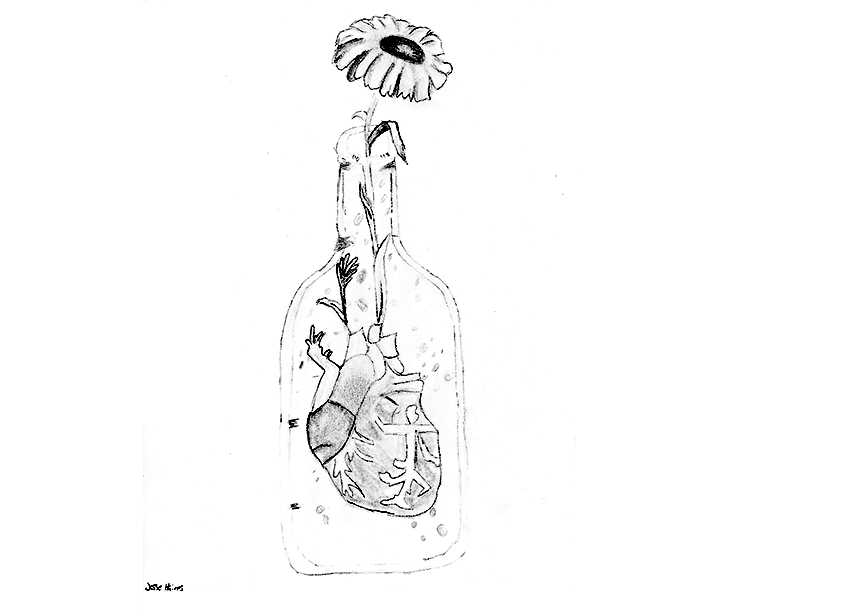

Students from Mennonite schools and congregations were invited to submit artwork on the topic of hope. See below for more submissions.

For discussion

1. Can you think of a time when you were disappointed because things didn’t work out as you had hoped? How is that feeling different from losing all hope? As you look at our world today, where are people generally hopeful that the future will be better? Where is there a feeling of despondency that things are getting worse?

2. Janet Bauman writes that her sense of hope is “associated with faith that God’s love is stronger than any other force and that, in the end, love wins.” How deeply do you share that hope? Have you ever doubted that good will eventually triumph over evil? How does the Christmas story speak to that hope?

3. Bauman acknowledges that hope can be “an empty platitude” or a mirage that can lead to complacency and inaction. Do you agree? What are some examples of how we can demonstrate hope by sharing God’s love? What can ordinary Canadians do to work toward improved racial justice?

4. Has your understanding of despair and hope been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic? What does it mean to “rest in the shadow of hope” in these times? What are some ways that you can nurture hope in others this Christmas season?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.