I left the jail one Monday morning last month feeling a heaviness that I have not felt in some time.

I don’t go there each Monday with some big agenda—I’m not there to reform or convert or instruct, but to listen, to pray, to encourage. But most days, I get a glimpse of goodness through a conversation, a smile, a new insight into the human heart and the human predicament.

Not that day, though.

Travis (a pseudonym) was the only one who came to the meeting that day. There were rumours of others who might join, but he came alone, looking slightly apprehensive, a sly grin poking around the edges of his mouth.

He was tall, lean, young and strong. Twenty years old, jet-black hair perfectly manicured in the fashion of the day, tattoos and scars peeking below the rolled-up sleeves of his coveralls.

He offered his story in bits and pieces over the next hour or so. He’d grown up on a reserve north of Edmonton, one of 16 kids in a patchwork family thrown together by the various configurations his parents had found themselves in over the years.

Dad abused mom, mom abused him as an outlet for her pain, he abused right back, swearing, stealing, leaving, coming back.

Kicked out of the house at 14 and then bounced around the city with siblings.

“I got behaviour issues,” Travis said. “I yell when I get excited, only when I get excited. I say what I don’t want to say, and I can’t say what I want to say.”

He leaned back on his chair, eyes restlessly darting around the room. He hasn’t seen his mom for two years, has no idea about his dad, doesn’t really care.

He’s got two kids of his own, he said. I look at him and smile. He reminds me of my son—big, kind, unpredictable, hard to read sometimes.

He told me he played football, basketball and volleyball when he was younger.

“I liked sports,” he said. “I was good at them.” His voice trailed off. My heart ached for this big kid, impossibly already a father.

“What are your kids’ names?” I asked.

“My daughter’s name is Genesis,” he replied. “My son… um, I don’t know. His mom won’t talk to me… I think he’s mine, I don’t know.”

He looked down as an awkward silence descended.

“Genesis,” I said. “That’s a cool name. Do you know what it means?”

He smiled.

“Yeah, it means like new beginning or something, right?”

I smiled.

“Yeah, that’s right, Travis.”

He went on to tell us that he has Tourette syndrome. He’s never been formally diagnosed, he’s never even told anyone, but he’s pretty sure that’s why he finds everything so hard, why he’s always getting into trouble, why he can’t fit in and just behave himself.

I thought of a boy growing up on a reserve, impossible family situation, with a condition that nobody knows about, constantly getting into trouble, nobody knowing how to help, how to make anything better, how to try something different.

I thought about what might happen when he gets out in a few months. I thought about the religious words I traffic in—words like “hope” and “love” and “change” and “freedom” and “redemption.”

I looked over at Travis, head down, eyes on the floor, all alone in a circle of churchy do-gooders trying to “make a difference.” The words didn’t seem to fit.

I thought of the cycles of violence and addiction and dysfunction that he has been raised in, of the structures and systems that relentlessly discriminate against his people, of the innumerable things that are working against him.

It’s too much, I thought. Who can climb out from under all that?

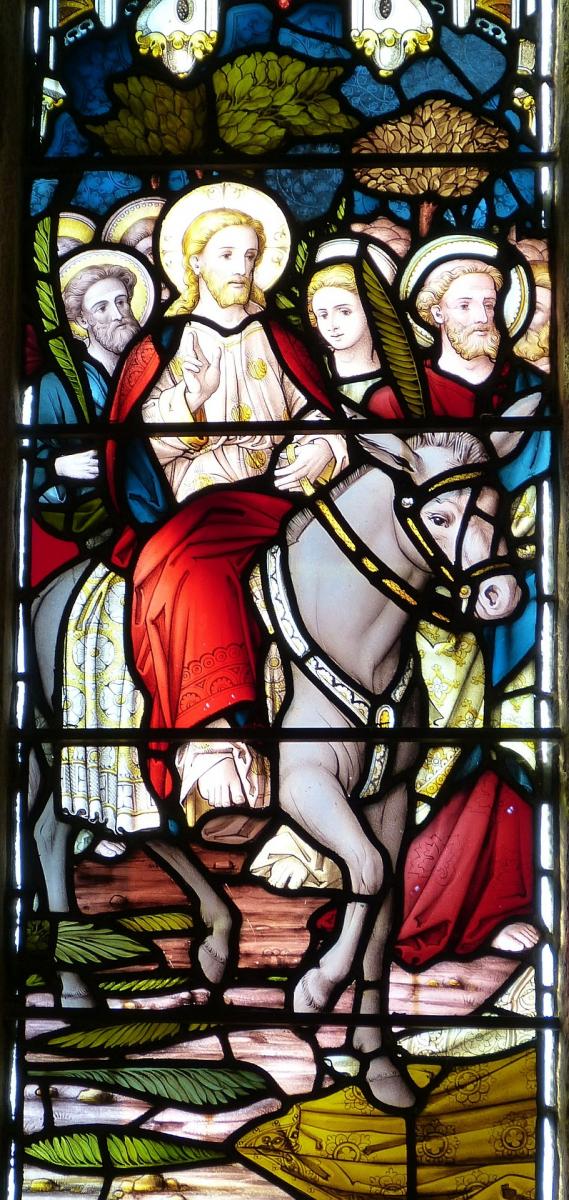

During the previous morning’s sermon—Palm Sunday— I reflected on what Jesus might have experienced as he sat outside the gates of Jerusalem, taking his first steps toward his inevitable death.

I focused on the human emotions and experiences that might have been roiling around in his head. I reflected on these things through the lens of Psalm 31 and landed on the hopeful truth that God knows what it’s like to be human.

I preached these words:

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to be deeply and persistently misunderstood.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to be betrayed by people that you love, people you had poured the best part of yourself into, people you expected better from, people from whom you had hoped for more.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to be afraid, to have that sinking feeling of dread in your stomach, to have your mouth go dry and your strength fail.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to feel helpless and angry at the inevitability of how things tend to go.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to feel like the bad guys always win.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to feel used—to be loved and adored only when you’re giving people what they want, when you’re putting on a show.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to be abandoned and to feel utterly alone.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to be mocked, ridiculed, dismissed.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to be seen as a failure.

Because of Jesus, God knows what it’s like to suffer and to die.

These are some of the hardest things we experience as human beings. And because of Jesus, God not only knows what they feel like, but enters right into them with us.

God knows what it’s like to be human from the inside.

Because of Jesus.

I spoke these words Palm Sunday morning to a room full of mostly white, mostly middle-class, mostly Christians. And they felt hopeful and good and true. They still do.

Mostly.

But would these words be any use to Travis? I desperately want to believe that they would, and I hope to get the chance to tell him. But they felt hollow as I walked out of the jail that morning. I felt like weeping for all the people like Travis in the world who seem to barely have a chance.

I thought about Travis’s daughter.

Genesis.

That’s the only religious word that seemed to fit that day.

Ryan Dueck is the pastor of Lethbridge Mennonite Church in Lethbridge, Alta. He blogs at ryandueck.com, where a version of this post originally appeared.