In 2012, I spent two memorable hours in Smithers, B.C., with Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Na’Moks (John Ridsdale), one of the chiefs at the centre of the Coastal GasLink crisis now confounding our nation. I also spent time with the chief and other members of the Haisla Nation, which supports the pipeline.

Back home in Manitoba, I have worked with—and still do—leaders elected under the Indian Act. I’ve also worked for a highly innovative Indigenous government established outside the Indian Act (not hereditary, but traditional).

I have worked smack in the middle of a situation in which one Indigenous nation—supported by Mennonite Central Committee—fought against a big project while other First Nations aggressively supported it. Incredibly awkward and incredibly important.

I’m not an expert, but based on my experience I think many supporters of the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs and blockaders cling to a right-wrong, black-and-white narrative that is overly polarized, overly simplified and ultimately untenable.

The whole thing is complicated and messy. The case I try to make below is that to short-circuit the complex reality is to miss the turn-off to the path forward.

I absolutely believe that the free, prior and informed consent of the hereditary chiefs should be required for the pipeline to proceed. I also acknowledge that other Indigenous bodies have given their free, prior and informed consent. I cannot just ignore or dismiss this latter fact, as some activists do.

As for blockades, to the extent the hereditary chiefs have shown support for blockaders, I echo that support. I have been involved in, and associated with, numerous illegal actions in support of Indigenous well-being. (And I have been at demonstrations that felt like unhinged public group therapy sessions.)

Of course, others will feel less supportive of the chiefs and blockaders. That doesn’t necessarily make them racist, xenophobic, colonial privilege-mongers—though some may well be. We are all stuck here together in this society, for better and worse, and we need to find a healthy way to co-exist.

Starting point

I did not arrive at my support for the hereditary chiefs automatically. My starting point was the time I spent with Na’Moks.

He was congenial, articulate, gracious, humble—the kind of person I would want to have a beer with or introduce to my young kids. There was also a deep fortitude about him.

During our 2012 conversation at the Office of the Wet’suwet’en in Smithers, B.C., we talked mostly about the Northern Gateway project, a highly contentious pipeline that Enbridge was hoping to build to carry diluted bitumen from the Alberta oil sands to tidewater at Kitimat, B.C., following a path similar to that of the proposed Coastal GasLink pipeline through Wet’suwet’en lands.

He also gave me a tour of their two-storey office building. One room was rimmed with floor-to-ceiling shelves laden with binders. This was the documentation from the Delgamuukw case, a landmark Supreme Court battle that the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en and neighbouring Gitxsan won in 1997.

The Wet’suwet’en boardroom contained a large table they received from one of the courthouses as a sort of trophy.

Anyone who cares about Indigenous rights in Canada knows Delgamuukw. The decision fleshed out the concept of Indigenous title and encouraged government to make a treaty with the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan. (Which hasn’t happened. Oops.)

My point: While there is an obvious diversity of voices and jurisdictions within Wet’suwet’en territory (hereditary chiefs, elected chiefs, province, feds), the hereditary chiefs have a considerable degree of legitimacy and stature, as well as a formidable track record.

Other point: I learned in a couple hours what governments and TC Energy—the company behind Coastal GasLink—are only learning now, the hard way: if you trot onto Wet’suwet’en territory and start building a massive project without the hereditary chiefs on board, you are in for a serious fight. Governments and TC Energy showed astounding ignorance in this regard.

They could have, and should have, worked all this stuff out in advance, as the Supreme Court advised.

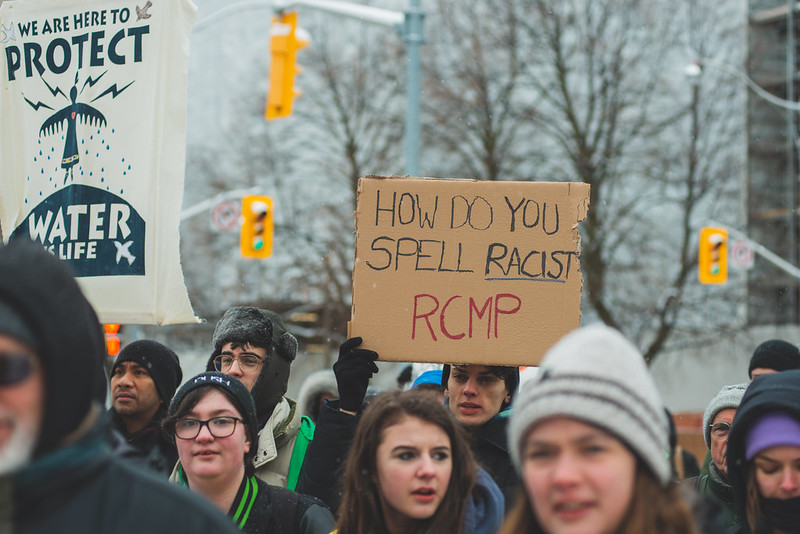

Then, for the RCMP to go in with helicopters, military-style fatigues and automatic weapons pointed at demonstrators in a pre-dawn raid was to maximize the chances of a massive escalation of conflict. They insulted and humiliated the Wet’suwet’en. Again, whether or not one agrees with the hereditary chiefs and land defenders, that was, at very best, a strategically ham-handed move on the part of whoever approved it. It pretty much guaranteed the demonstrations would spread. I would also argue it was morally wrong.

As for rail blockades, Justin Trudeau and company got what they asked for. You can’t poke the bear, slap the bear and then kick the bear and not expect a bit of a growl.

As for the companies and people who complained about being inconvenienced, don’t forget the inconvenience of residential schools, laws forbidding your cultural and spiritual practices, no treaty even though you won at the Supreme Court, and generations of exclusion from the Canadian economy.

If some of those chickens come home to roost, don’t complain.

Of course, many will disagree. And some will argue that the blockade strategy has been counterproductive.

Lessons of a pipeline stopped

The reason I was in Smithers to interview Na’Moks in 2012 is that it appeared that the Northern Gateway project was headed towards a major, potentially Oka-like conflict (a point I made in this Huffington Post article). I wanted to write about Northern Gateway resistance and I wanted to make some connections that would be relevant if the situation came to a point where people from across Canada needed to literally stand with Indigenous people in northern B.C.

I spoke with various leaders along the Northern Gateway route. The message was clear and unanimous: leaders, and a great many others, were literally going to stand in the path of bulldozers if it came to that. There was no doubt they were serious. This included both hereditary and elected leaders.

They also said, “We are not against development per se.” A lot of supporters elsewhere in the country didn’t get this. Many probably didn’t want to, preferring a romanticized, idealized version of Indigenous identity.

For and against fossil fuels

I was interviewing Gerald Amos, a Haisla elder-fisherman-advocate, in a hotel restaurant in Prince George, when Ellis Ross, the Haisla Nation chief at the time, swooped in, instructed me that everything was off the record (but did not ask me to leave), and gave Amos an intense briefing about how Enbridge had offended everyone, and how the chief was in the thick of a major play for a stake in multi-billion-dollar natural gas developments. All of that has become public knowledge, including in a 2016 Globe and Mail profile of Ross, who is now a Liberal MLA in B.C.

The Haisla town-site of Kitamaat Village sits across the narrow Douglas Channel from where Northern Gateway bitumen would have been loaded onto supertankers and, likewise, where the Coastal GasLink products would transfer from land to sea.

To be clear, Ross was dead set against Northern Gateway, but eager for natural gas development.

From previous experience, I knew Indigenous leaders often feel caught between environmental concerns and a desperate need for employment for their members, but still, I was surprised by the chief’s eagerness for fossil-fuel mega-development.

Activist over-simplification

Many anti-Northern Gateway activists and allies viewed the Haisla and others as opposing fossil fuel development per se and serving as a sort of ultimate line of defence in protecting Mother Earth. That was an oversimplification, and still would be today.

In fact, the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs proposed an alternate route for the Coastal GasLink project that they would have potentially agreed to. In 2012, Na’Moks told me, “We are not against development.”

Indeed, Indigenous people from coast to coast are participants in—and proponents of—mines, oil sands development, massive hydropower dams and pipelines. I don’t think it would be accurate to say that a large majority of Indigenous people or governments are categorically opposed to large-scale industry resource development projects. Put that on a placard.

(I happen to have years of first-hand experience working with Indigenous people opposed to new hydroelectric dams in Manitoba. Meanwhile, five First Nations are partners in those dams, although much less enthusiastically now. That is the awkward reality. There is no way to pretend there is only one legitimate Indigenous voice. I did not agree with the pro-dam First Nations or their dirty tricks, but they did have the right to benefit from large-scale industrial development, as most of us have our whole lives. I still chose to fight them, after face-to-face discussions, and they fought back.)

Despite federal approval, years of preparation and many millions already sunk into Northern Gateway, the project died. Ottawa implemented a tanker ban. Indigenous groups went to court. Enbridge backed away. It was clear that the vast majority of Indigenous communities between Prince George and Haida Gwaii were vehemently opposed. They predicted they would win, and they did.

Coastal GasLink is different. There is not a clear majority of affected Indigenous peoples opposed. Surprisingly, I have heard nothing about people in the vicinity of the fracking opposing the project. From what I have heard, the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and some Gitxsan hereditary chiefs are the only vocal opponents along the Coastal GasLink route.

At the same time, I find it notable that very few Indigenous groups are vocal in their support for the project, despite 20 First Nations having signed agreements related to the pipeline. My guess—and it is only a guess—is that some parties that signed on to the project may have done so reluctantly. Their agreement may be much softer than Wet’suwet’en opposition.

Why is opposition to Coastal GasLink so much weaker than opposition to Northern Gateway was? Diluted bitumen—which Northern Gateway would have carried—is heavy goo that is extremely hard to clean out of waterways in the case of a spill in a river or at sea. In contrast, natural gas dissipates into the air—not great, but it would not permanently destroy clam beds or spawning grounds. What I heard in 2012 is that some people were more afraid of diluted bitumen for this reason.

Are elected leaders illegitimate?

Sometimes activists and allies try to simplify the Coastal GasLink situation by ignoring or dismissing all Indigenous voices that do not align with the hereditary chiefs, whether those are elected Wet’suwet’en chiefs or elected chiefs elsewhere along the pipeline route. The argument is that these leaders are elected under the rules and authority of the Indian Act. That argument is too convenient and too dangerous.

Most First Nations elect chiefs and councils under the Indian Act rules. The Act stipulates how elections happen and the leaders thus elected are the ones governments deal with.

The system was forcibly and insensitively imposed by the Canadian government. It ignores how people organized themselves previously and ignores their right to organize as they choose. It was and is paternalistic, damaging and stupid.

I had the privilege of working for Pimicikamak Okimawin, an Indigenous government set up outside the Indian Act. This Cree nation, based at Cross Lake, Man., established its own election law according to its own traditions and then, out of courtesy, informed the feds. Ottawa did not want to recognize it. Pimicikamak said, we’re not asking you to, we’re letting you know this is how we are doing things. Ottawa relented. It was not a hereditary system, but it was traditional and independent.

What Pimicikamak did, that the Wet’suwet’en do not seem to have done, is make very clear the lines between the Indian Act system and the traditional system. For Pimicikamak, the traditionally elected leaders also served as “chief and council” under the Indian Act, because you need that structure if you want health, education and other funding from Ottawa.

Many First Nations do not have this sort of system or clarity. The problem I see with claiming that leaders elected under the Indian Act are illegitimate, is that in many places there is not a functional, locally recognized alternative.

I do not know the situation of each First Nation along the Coastal GasLink route, but I know that in many places in Canada, the people elected under the terribly flawed Indian Act system are the closest thing to being locally recognized representatives of the people. You can’t just pretend their voice does not count because you do not agree with them. I know wonderful people who are “Indian Act” chiefs and councillors. I spend many evenings doing work to assist them.

Do Indigenous people have the right to support natural gas?

Crystal Smith, the elected chief of the Haisla Nation, voiced support for Coastal GasLink last year, saying: “I’m tired of managing poverty. I’m tired of First Nations communities dealing with issues such as suicide, low employment or educational opportunities.” She repeated her support for Coastal GasLink during a speech in Prince George this January.

I wish she were opposing the project, but I will not for a second say that her view, or her position as leader, is illegitimate. I would challenge those people who dismiss elected leaders to make that argument to Smith’s face. You will lose.

I would note that, when elected chiefs were opposing Northern Gateway, activists and allies were more than happy to recognize them as legitimate.

I also wonder why we do not hear from a lot more hereditary chiefs elsewhere along the Coastal GasLink route.

None of this means the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs are wrong or not justified. Personally, I hope they stop the project.

But there might be something bigger at play than this one project.

In 2016, I interviewed Bill Phipps. He was once the moderator of the United Church of Canada and has long been a spirited, on-the-ground worker for Indigenous and environmental causes. He lives in Alberta.

Somewhat to my dismay at the time, he said he didn’t think so much focus should be on yes-no debates about specific pipeline projects. Rather, we should discuss a broader vision forward for society.

That sounded soft to me. But I thought about it. Instead of simplifying single issues and drawing stark, polarized battle lines, maybe we would do better to dive right into the complexities, and the range of interests, and the reality that each of our own lives are likewise complex and contradictory.

UNDRIP: Double-edged sword

Mennonites and other church folk, led by the tremendous efforts of Mennonite Church Canada’s Steve Heinrichs, have directed much attention to getting the federal government to enshrine the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in Canadian law.

What sets UNDRIP apart from existing and more enforceable UN documents with many similar provisions is the notion of free, prior and informed consent. This can be seen less as a veto than a commitment to a process that involves everyone from the very start in such a way that a project that cannot be brought forward in an acceptable way will be set aside before it gets to a point of conflict.

I would venture that people advocating for UNDRIP legislation—which Trudeau has said he will bring forward—assume that Indigenous people would use this tool to reject major resource developments. That is naive.

I fully support the notion of free, prior and informed consent. And I know that many times Indigenous people will freely consent to projects I would rather see die. That is exactly what is happening with Coastal GasLink. Advocates need to be prepared for this.

Words on paper

Last November, the B.C. legislature became the first in Canada to approve a bill that requires the province to bring its laws and policies in line with UNDRIP aims. Less than three months later, the biggest Indigenous conflict in Canada in years erupted in B.C.

A law is words on paper. It is a tool that is often only as good as the degree of power of those who wield it. Sometimes you have to go to the Supreme Court of Canada to ensure a law is followed. And, as the Wet’suwet’en know all too well, sometimes that is not even enough. The Delgamuukw case took 13 years and then governments ignored it.

Ultimately, it is only a shift in the complexion of society that brings change. I believe that shift is more likely to happen through candid and constructive consideration of complexities, nuance and awkward contradictions. Coastal GasLink provides a perfect opportunity.

As the chief justice writing the Delgamuukw decision concluded: “Let us face it, we are all here to stay.” That includes elected chief, Crystal Smith; the hereditary chief, Na’Moks; as well as pipeline-rabid Jason Kenny, and those protesters in Winnipeg yelling “F–k the police!” who, by the way, should know what Na’Moks said in an interview published after the RCMP raids: “Under the uniform of the RCMP are human beings.”

He should know, his daughter is an RCMP officer. That’s how beautifully messy our country is.

Related stories:

In response to blockades: prayerful pause

Who do you support when a community is divided?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.