There has been remarkable growth in the number of Old Order Mennonite meetinghouses in Ontario in the last 50 years. They have been spreading farther afield, especially in the last 20 years. Amsey Martin, an Old Order deacon and schoolteacher, and Clare Frey, a minister from the Markham-Waterloo Mennonite group, talked about this growth at a meeting of the Mennonite Historical Society of Ontario, held at Floradale Mennonite Church on October 24, 2015.

Old Order Mennonites are traditionalists who resist adopting modern expressions of faith and culture. Most of them are small farmers. Generally “Old Order” means they use horse-and-buggy transportation, although this article considers the Markham-Waterloo Mennonites as a kind of Old Order group.

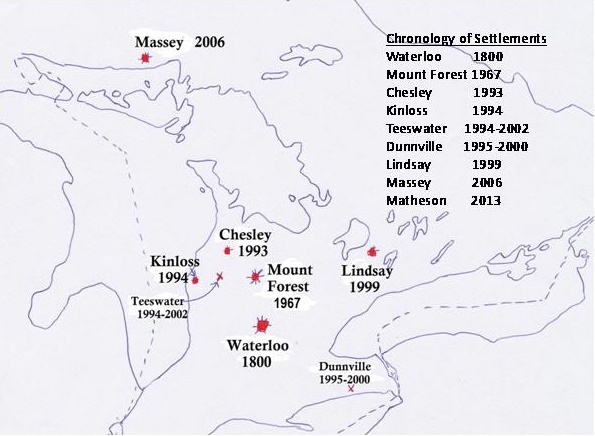

Martin put together a chart showing that between 1901 and 1955 there were no new meetinghouses built. Until the 1970s, they were all in the northern part of Waterloo Region or just across the boundary in Wellington County. Beginning in the 1970s, a new community began in the Mount Forest area, about 60 kms north, and the Waterloo community has been spreading north and west into Wellington and Perth Counties. Since 1998 several other new settlements at further distances have resulted in many more meetinghouses.

Frey, who enjoys collecting information about other plain Mennonite groups, reflected that this growth and spread is happening in other Old Order communities in the U.S. as well. He also explained that in the 1800s, Mennonites were spreading throughout southern Ontario, but in the end, many of the small outlying churches didn’t survive.

He described one failed settlement of the 1880s, when a group who moved to Iowa was zealous about having a plain, traditional and “pure” Mennonite Church. The Iowa settlement collapsed in less than 20 years and the people moved back to established Mennonite centres. Frey said that descendants of the Iowa migration who returned to Waterloo County were very negative about new settlements.

When the Ontario Old Order Mennonites split from the mainstream Mennonite Church in 1889, they had 15 places of meeting: four in Waterloo County; four in the Markham area; two in Vineland; two in Cayuga; two in the Zurich area; and one in New York state. In the next 50 years, most of those meeting places became extinct. The impact of all these closures was the mentality that you stay close to home, you don’t venture out to new places, said Frey.

The first half of the twentieth century was a time of contraction for the Ontario Old Order Mennonite group. Both Frey and Martin pointed to the following reasons for this lack of growth. In the 1910s a stricter group (known as the David Martins) broke away. In the 1930s a Bible Chapel began in Hawkesville, made up of former Old Order Mennonites, and through the ‘20s and ‘30s a number of families joined Mennonite Conference of Ontario churches such as St. Jacobs, Elmira and Floradale.

The Old Order group divided again in the late 1930s. At the beginning of the decade the Old Orders in Markham and Rainham/Cayuga stopped affiliating with the group in Waterloo. In 1939 the Old Orders in Waterloo County divided with the formation of the Markham-Waterloo Mennonites who affiliated with the Old Orders of Markham. A major point of contention was that the Old Orders of Waterloo refused to adopt the use of cars; they still use horse-and-buggy transportation today.

Martin also reflected on why the Old Order church was expanding by the 1950s and ‘60s with fewer families choosing to leave the church. Martin believes that the leaders in the latter part of the twentieth century were better able to articulate a sense of what it means to be Mennonite/Anabaptist and the rationale for being plain and separate from the world. Perhaps earlier leaders were reacting to the 1889 split and were careful not to sound like the “other” Mennonites. By the 1960s, leaders were clearly teaching New Testament principles, explaining salvation and encouraging scripture reading.

In 1964, Pathway Publishers began printing magazines from an Old Order perspective, and Martin believes this had a large impact on the broader Old Order community. Many Old Order families received the Family Life, the Young Companion and the Blackboard Bulletin on a monthly basis and were influenced by the articles explaining the need for separation from the world and the stories showing people living simply and biblically.

Martin also pointed to Mennonite historian Sam Steiner’s observation that the Old Order church grew after they began organizing their own parochial schools. Martin said he didn’t believe it at first, but on reflection it began to make sense.

“As an educator myself, I find that fascinating, but I shake in my shoes at the huge responsibility of us parents and teachers,” he remarked. He followed that with a prayerful quote from the hymn, “O God, our help in ages past, our hope for years to come.”

Both the Markham-Waterloo and Old Order Mennonites began building new meetinghouses in the 1950s and have spread mostly north and west from their original home in Woolwich Township, Waterloo Region. The town of Elmira is still in the heart of the settlement, but today many of these traditionalist Mennonites do their shopping in towns like Listowel, Harriston or Mount Forest.

The Markham-Waterloo Mennonites have begun two outlying settlements, one in Beachburg in the Ottawa valley, begun in 1980. The congregation of North Haven was organized in 2009 in a new settlement near New Liskeard in northern Ontario. A church building was erected in 2010.

The Old Orders have more outlying communities. The Chesley area, begun in 1998 has one meetinghouse. The same year a new community began in Kinloss Township, north of the town of Lucknow. Today that area has three meetinghouses: Martinfield (1998); Langside (2007); and Clover Valley (2011). In 1999, a new community began in the Lindsay area, more than 100 kms northeast of Toronto, and a meetinghouse was built in 2009.

At an even greater distance are communities in Massey, west of Sudbury, and Matheson, east of Timmins. Today Massey has two meetinghouses: White Pine (2009); and Lee Valley (2010). A meetinghouse was built in Matheson in 2014.

Both Frey and Martin indicated that new settlements are started by lay people, not church leaders. When enough families have settled in an area to organize a congregation, then the church leaders get involved. Two Old Order settlements that never got off the ground were Teeswater (1994-2000) and Dunnville (1995-2000). In these cases, not enough families moved to the new settlement to begin a congregation and eventually it folded.

For both groups, many of their meetinghouses serve two congregations. Congregations meet every other week, and on the intervening Sundays the people visit other congregations. The territory around the meetinghouse is divided into two geographical units and they become two congregations sharing one meetinghouse.

To close his presentation, Martin said, “If the Old Order Mennonites are going to remain a farming community, if our farms are going to be affordable and viable, if they are going to be small family farms, if we are going to retain a measure of separation from the world, then we need new communities. We need to spread out.”

—Corrected June 23, 2020

Related stories:

10 things to know about Mennonites in Canada

Books show Old Order Mennonite culture from the inside

Poetry, paintings bring Old Orders to life

Pennsylvania Dutch a language with merit

History surprises

Meet me at the Grand!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.