Historical experiences of ordinary people living out their faith were shared at a travelogue presentation of Russian Mennonite migrations in Europe and Central Asia.

The presentation, co-hosted by Mennonite Heritage Archives and TourMagination on Sept. 13, encouraged people to see travel as a tool to gain deeper understandings of how the unique historical experiences of Mennonites have shaped beliefs and values.

“Our tours help people of faith explore, experience and expand their worlds,” said tour leader John Sharp, a recently retired history and Bible professor at Hesston (Kan.) College.

Sharp has led four tours to Uzbekistan that reflect on some of the experiences of 43 Mennonite families from South Russia, now Ukraine, who established the village of Ak Metchet near the historic Silk Road city of Khiva in the 1880s.

These families have left a legacy of positive and cooperative interactions with their Muslim neighbours, said Sharp. Their friendships paved the way for new generations of Mennonites to continue developing and expanding interfaith dialogue.

“The more we get to know each other, the more likely we are to understand each other,” he said, adding, “This was important in the 1880s and is important today.”

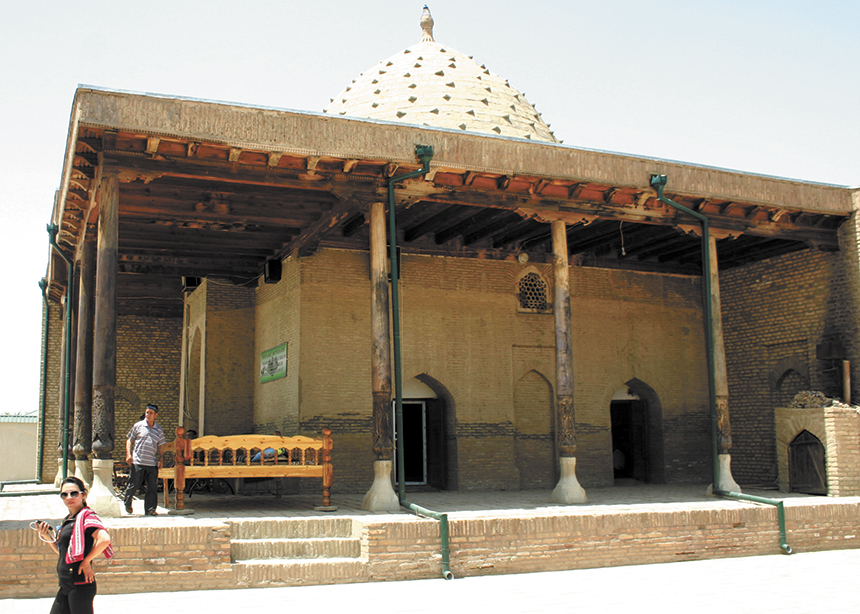

Sharp enjoys visits to the village of Serabulak, where this group of Mennonite pilgrims were stranded during the winter of 1881-82. They had lived through many hardships on this journey, but in Serabulak they received a warm welcome and were given permission to use the Kyk-Ota Mosque for worship services, baptisms, weddings and funerals. Five Mennonites are buried in the cemetery.

“This is amazing hospitality,” said Sharp.

In the spring of 1882, the Mennonites hired camels to continue their journey to the walled city of Khiva. “This is the only Mennonite migration that I know of that hired camels to cross a desert,” he says.

A merchant in Serabulak had given Mennonite pilgrims a farewell gift of money and other gifts. When Sharp met one of the merchant’s descendants, Mr. Karimov, and asked him about this gesture of friendship, Mr. Karimov responded: “Because it’s the teaching of the Prophet and the Qur’an to offer hospitality to strangers and immigrants.”

The Mennonite pilgrims established a settlement near Khiva. Local people named the settlement Ak Metchet (“white mosque”) because the Mennonite whitewashed church was a sharp contrast to the impressive mosaics and architecture of Islamic mosques.

“There is still plenty of evidence that Mennonites once lived there,” said Sharp. “German-Russian Mennonites seeking escape from the world became modernizing agents in Central Asia. They introduced new agricultural crops, methods, implements and new breeds of livestock.”

Mennonites worked in the Khan’s palace and helped build and decorate palaces that are still standing today. Mennonites lived in harmony with their Muslim neighbours for a half-century. In 1935, they were deported by Joseph Stalin.

Over the years, Muslim families have passed down this deportation story to their children. “They say when Mennonites were deported it was like our own children were torn away from us,” said Sharp.

Sharp’s travelogue also included stories and images of other tours that explore Anabaptist theological roots and Mennonite migrations. Following the presentation, Darrel Toews, pastor of Bethel Mennonite Church in Winnipeg, said that the travelogue reminded him of some of the memorable experiences he had during a heritage tour.

An unforgettable experience was standing on a fisherman’s wharf on the Limmat River in Zurich, Switzerland, said Toews, adding, “It deepened our understanding of the strife and fervent of the Reformation.”

During the 16th century Reformation a bitterly divisive conflict between the state Reformed Church and the Anabaptist movement arose because Anabaptists rejected infant baptism as unbiblical. Felix Manz, an early Anabaptist leader, was rebaptized and was an advocate for believer’s baptism.

In Zurich, a law had been passed that rebaptism was a crime punishable by drowning. On Jan. 5, 1527, Manz was drowned in the cold waters of the Limmat River. “They called it his third baptism,” said Toews. “As Mennonites, we practise adult baptism. It was a very powerful moment.”

As part of the reconciliation efforts between the Reformed and Anabaptist churches, a memorial plaque has been placed on the fishermen’s wharf to remember Manz and other Anabaptist martyrs.

Reflecting on the travelogue, Karl Koop, professor of history and theology at Canadian Mennonite University, said that travel tours generally focus on the positive aspects of Anabaptist faith and culture. While he encourages his students to take pride in the positive stories of Mennonite faith and culture, he also urges them to look realistically at negative stories that could require their own repentance and reconciliation.

“It is important to be really cognizant of the positive and negative stories,” he said. “Many Mennonite churches were formed out of conflict. Churches are still experiencing conflicts and divisions today. We need to look long and hard at the negative stories and learn from that as well.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.