Research shows that rates of domestic abuse are just as prevalent in religious communities, and even higher in more conservative forms of religion, says Val Peters Hiebert, assistant coordinator of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Manitoba’s Abuse Response and Prevention Program, which helps congregations navigate disclosures of abuse and cases of sexual misconduct by clergy.

Hiebert and Jaymie Friesen, the program’s other coordinator, develop policies for churches to follow during these processes and offer preventative education workshops around Manitoba. They also offer victim-survivors support groups, a resource library and referrals to other services.

Hiebert became interested in researching domestic violence while teaching at a Christian university. When she covered the topic in her courses, countless students disclosed to her their experiences of abuse.

“At that point I thought, is this just anecdotal, or what’s going on here?” she says. “I started digging around the research and realized: ‘Wow, this is a really significant issue that doesn’t get a lot of coverage.’ ”

People often assume domestic violence isn’t a problem in their context if they don’t hear about it.

“That’s just not the case,” Friesen said in a 2020 interview with Mennonite Church Canada. “If you’re not hearing about the impacts of abuse on people’s lives, what that actually says is the church isn’t a safe place to talk about abuse.”

The reality is, telling someone about domestic abuse is extremely difficult. These experiences stay hidden behind closed doors because survivors fear being doubted and ostracized, or because they are pressured to keep quiet.

People don’t want to believe the accusations made against someone they know and love, like a parent or grandparent, Hiebert says, especially in religious contexts, where the institution of family is venerated. Others find justification in Scripture, pointing to passages that say women should submit to their husbands, or in church structures, in which men occupy leadership roles.

This was the case for Gloria Froese, a victim of domestic abuse from the age of six until she was over 18. She was born to a Mennonite father and German mother, and grew up mostly in Steinbach, Man., attending the fundamentalist Church of God Restoration. Although the church is not formally affiliated with Mennonites, many adherents come from conservative Mennonite backgrounds.

“The next nine years were basically hell on earth,” Froese says of the routine abuse that intensified when her family joined the congregation. Any disobedience or distasteful behaviour was considered rebellion against God, and resulted in physical and verbal beatings, she says. No matter how hard she tried to be perfect, she says she couldn’t avoid the regular spankings, which created bruises sometimes stretching from her shoulders to her ankles. She now lives with chronic fatigue syndrome, which she attributes to the trauma of these years.

She remained silent because she was taught to fear the evil outside world and believe nowhere else would be as good. “The insular nature of it is probably the most problematic, that’s shutting out the world of being different and perpetuating this silence,” she says.

The extreme, secluded context of Froese’s experiences may not be familiar to many people, but its themes are more common. In small communities, where everyone’s lives are closely intertwined, the unspoken social pressure to not cause turbulence is heavy.

“It’s difficult work because abuse in the home is so hidden,” Hiebert says. “And people inside those homes have lots of motivations to continue to hide it, because it’s shaming, it damages the reputation of the church or the family. But that silence actually perpetuates it. How do we find ways to carefully and gently but firmly address that these kinds of things are going on in homes and we really need to talk about that?”

It’s increasingly important that victim-survivors are offered safe environments, people and resources. Rates of domestic violence rose during the COVID-19 pandemic, as everyone was confined to their homes and isolated from each other.

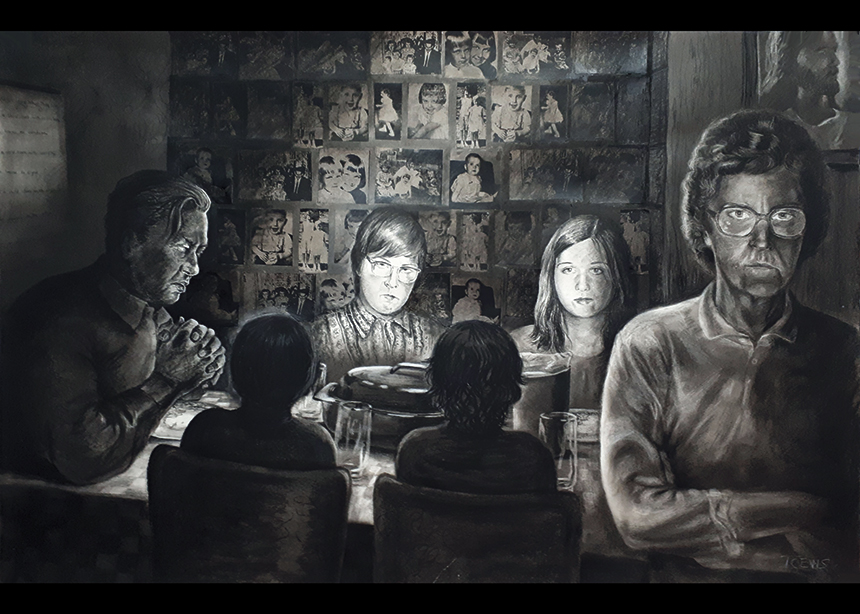

MCC’s Abuse Response and Prevention Program launched an updated website in 2020 and, earlier this year, the Mennonite Heritage Centre Gallery hosted the exhibit, “Breaking the Silence on Domestic Violence,” which aimed to bring the issue of domestic abuse to the wider public.

The Mennonite church and broader Christian church need to talk more about domestic abuse so the topic is normalized, Froese says, adding that education is key.

Hiebert agrees, emphasizing pastors’ needs for training and access to external resources and assistance. “Most pastors of the Protestant evangelical tradition don’t receive any training in their seminary degrees about how to respond to domestic violence,” she says. “So pastors, who are typically overworked . . . often overtaxed and exhausted, then are dealing with situations for which they have no training.”

Friesen and Hiebert are co-teaching an intensive course at Canadian Mennonite University this coming spring, from May 8 to 12, entitled, “Power, Ethics, Abuse and Church Leadership,” which will explore healthy pastoral relationships, responsible stewardship of power, and healing-centred practices for responding to domestic violence experienced by congregants.

Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Manitoba? Send it to Nicolien Klassen-Wiebe at mb@canadianmennonite.org.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.