There was nothing unusual about it when Richard, Paul and Adele Armin walked into the recording studio on New Year’s Eve in 1986. It was just another job, really.

Music producer Daniel Lanois called Richard the day before and requested that the siblings, all professional musicians living and working in Toronto at the time, come to Grant Avenue Studio in Hamilton, Ont., to record string parts for an album he was working on: The Joshua Tree by U2.

Richard and Lanois had become acquainted through Toronto’s music scene. Richard frequently contributed cello parts to projects recorded at Grant Avenue, which Lanois co-founded.

“I was always happy to hear from Danny,” Richard told Canadian Mennonite by phone from his downtown Toronto apartment at the end of March, “because he always had really interesting projects.”

At around 7 p.m., the Armins sat down in the studio’s control room with their instruments. Lanois and recording engineer Bob Doidge played them “One Tree Hill,” the song they would be playing on. After listening to the song about 10 times, the Armins devised a simple arrangement and began recording. Their work was guided in part by U2 guitarist The Edge, who was on the phone with Lanois throughout the session.

Three or four hours later, the session was over. Ten weeks after that, the album was out, and people around the world could hear the Armins’ playing.

“It was a very devotional kind of song, and it was quite profound to listen to,” Richard said. “We approached it like a hymn—a Mennonite hymn—and, given our background, we knew how to do that.”

‘Mennonite churches gave us a start’

Marta Goertzen fell in love with, and married, a teacher named James Jay Armin, and together they gave birth to a string quartet.

Jay and Marta started their family in southern Manitoba in the early 1940s. Towards the end of the decade, the family moved to Leamington, Ont., where Jay was the principal of United Mennonite Educational Institute (now UMEI Christian High School). Marta was a homemaker and talented visual artist, having studied at the Brooklyn Museum School of Art in New York.

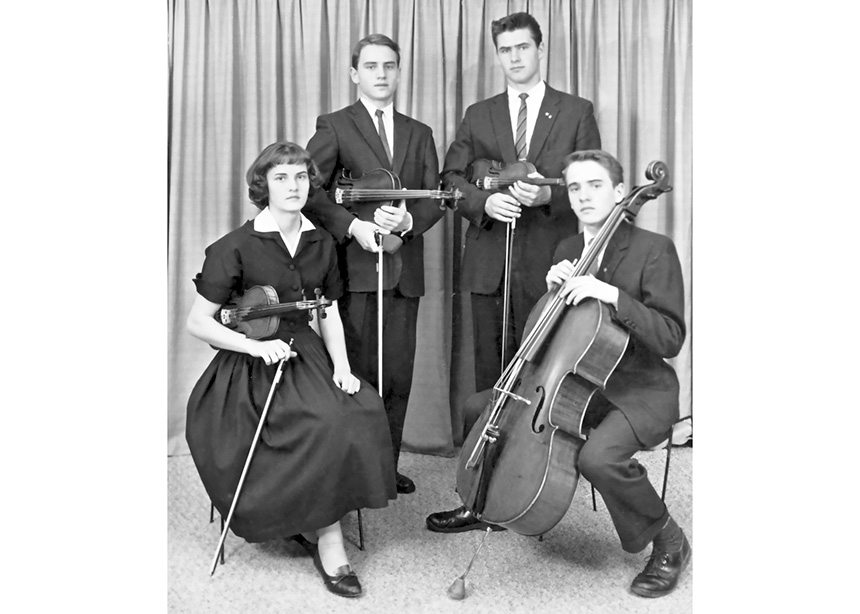

In 1953, the family moved to Riverside, Ont., a town that is now part of Windsor. There, the children started learning their instruments. Otto, the eldest, and Adele, the youngest, both took up the violin. Twins Richard and Paul picked up the cello and viola, respectively.

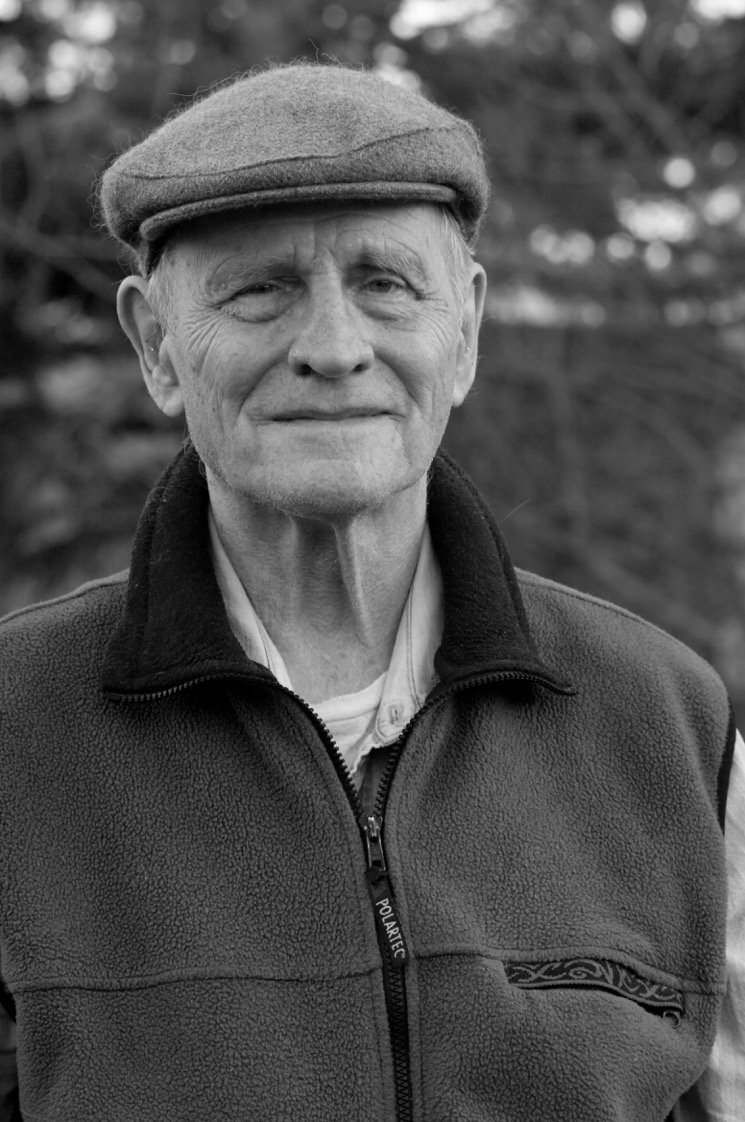

“We each had an affinity for [our] instrument,” Paul recalled when reached at his home in Pictou, N.S., last month. “We were able to play anything that was put in front of us after a while.”

Faith wasn’t an important part of the family’s life, but the cultural aspects of being Russian Mennonite played a vital role. The family spoke German at home, connected to Mennonite churches wherever they lived, and helped with the music at the churches they attended. The family travelled across Canada twice, with the children performing in Mennonite churches along the way. During the first tour, they billed themselves as the Mennonite Armin String Quartet.

“Mennonite churches gave us a start,” Paul said. “We were able to play lots of concerts and lots of different music, both folk music and the heavier classical works, for these audiences. . . . It was all Mennonite churches for our first few years of existence, that got us to a professional standard of playing.”

The quartet often performed on CBC radio and TV. In 1961, they were granted scholarships to study at Indiana University. After studying and performing together for a couple years, the siblings went their separate ways.

In their youth, none of them aspired to turn music into a career. Still, all four became professional musicians. Otto performed with various symphony orchestras across Canada before becoming first concertmaster with the Hamburg Philharmonic in 1977. Today, he is retired and still lives in Germany.

Adele toured extensively, played on hundreds of recordings, and was a member of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra for 20 years. At one point, she backed Sammy Davis, Jr. as part of an all-woman orchestra. She died in Oshawa, Ont., last July following a two-year battle with cancer.

Richard was a professional musician in the United States, and spent an eight-month stint working with Don Shirley, the pianist whose story inspired the Academy Award-winning 2018 film, Green Book. Eventually, Richard joined the Toronto Symphony for five years, followed by a five-year stint in the rock band Lighthouse. He worked as a session musician in Toronto for the rest of his career.

Paul’s career took him to New York, where he played on Broadway and studied at the Manhattan School of Music. Then he headed to London, England, where he performed with what is now the Royal Opera. When he returned to Canada, he performed at the Stratford Festival, joined the Montreal Symphony Orchestra for two seasons and toured with Lighthouse for a year. After starting a family, he settled down in Toronto and became a high-school teacher.

Richard, Paul and Adele did recording sessions together throughout the 1970s and ’80s, playing on everything from commercial jingles and films, to folk albums. In the liner notes to The Joshua Tree, they are credited as the Armin Family.

‘Unusual for string players’

On “One Tree Hill,” the Armins played electro-acoustic instruments they had developed, called Raads. Recording engineer Bob Doidge recalled the Armins being pleasant people who were nice to work with. “They didn’t really write anything out,” Doidge told CM last month. “They were good at winging it, which is unusual for string players—extremely unusual.”

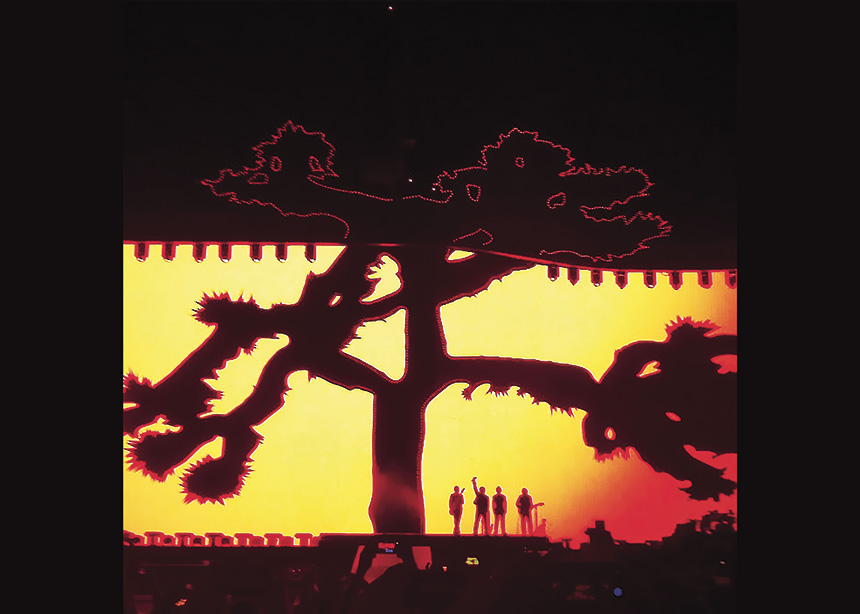

It’s safe to say that The Joshua Tree is the most famous album the Armin siblings appeared on. Released on March 9, 1987, the album—U2’s fifth—made the band superstars. It landed them on the cover of Time, produced three hit singles and earned them the Grammy Award for Album of the Year.

In the 36 years since its release, The Joshua Tree has sold more than 25 million copies, making it one of the world’s best-selling albums.

Given that the album includes the U2 classics “Where the Streets Have No Name,” “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” “With or Without You,” and “Bullet the Blue Sky,” it can be easy to forget about “One Tree Hill.”

Still, the song is significant in the band’s history. It’s about Greg Carroll, whom U2 singer Bono met in 1984 while on tour in New Zealand. On the first night they met, Carroll and his friends took Bono up One Tree Hill, one of the highest of Auckland’s largest volcanoes. Carroll started working for the band, and subsequently formed a deep friendship with Bono and his wife, Ali Hewson.

Carroll was killed in a motorcycle accident in Dublin on July 3, 1986. The lyrics to the song reflect Bono’s thoughts at his funeral.

In the memoir he published last year, Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story, Bono recalled the keyboard beat that provided the song’s genesis. “It became the foundation of a song we called ‘One Tree Hill,’ after the place overlooking Auckland where we had spent such a special time with Greg,” Bono wrote. “The song could carry the grief we could not.”

‘Back to our beginnings’

Paul agrees with his brother about the hymn-like quality of “One Tree Hill” and mused about the way the string parts resemble the hymn arrangements he and his siblings played when they were growing up. “In a sense, [U2] certainly got the right string players,” Paul said. “[We went] back to our beginnings.”

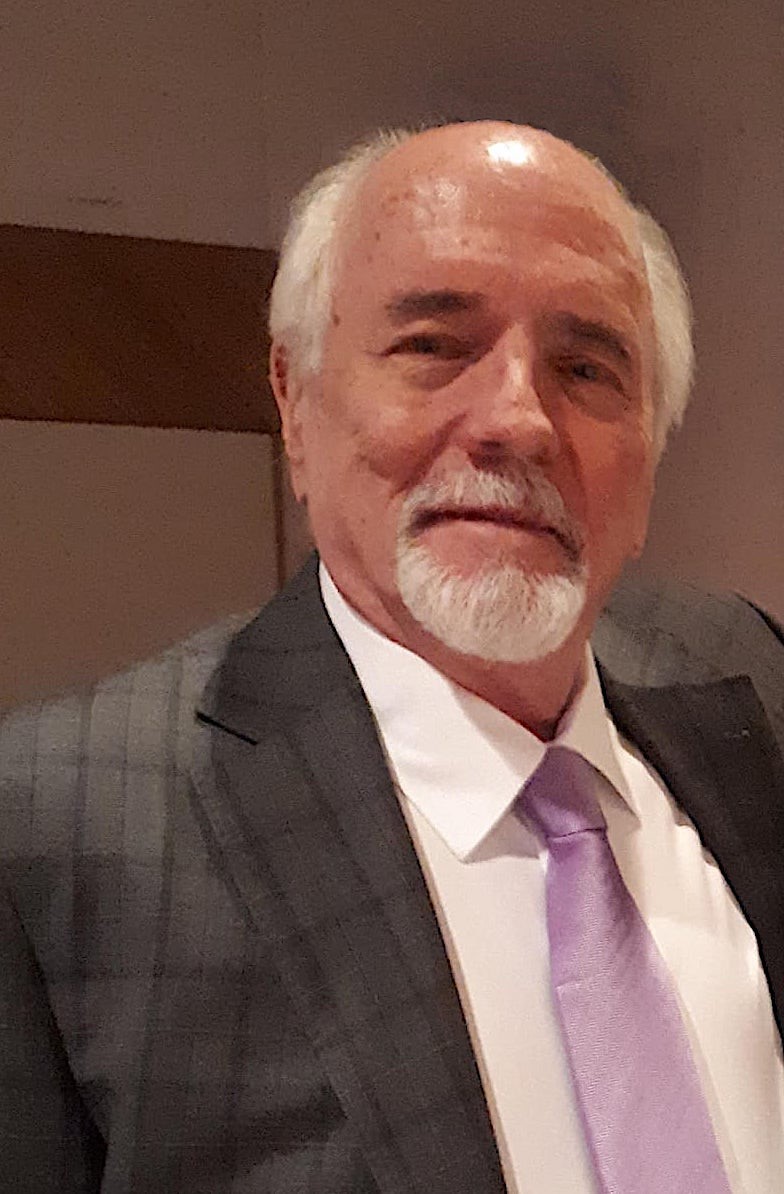

Neither brother is religious, although Richard describes himself as “spiritually oriented.” Now 78 and retired, he plays his cello occasionally, but in recent years has become more interested in silence. “I’ve discovered that, in silence, something goes on within us that is truly creative,” he said. “It doesn’t show outwardly, but inwardly. It’s a profound experience.”

More than 1,700 kilometres away, Paul is also retired. He has fond memories of playing with his three siblings, back when they had no intention of billing themselves as a string quartet and were simply drawn to making music together.

“We didn’t really play together so much as we listened [to one another], and the playing was automatic,” Paul said. “We had a lot of fun with the music.”

Above: “One Tree Hill” as it appears on The Joshua Tree. Below: A 2017 mix of the song by Brian Eno.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.