“Sir,” said the man, “you and your family can be very proud of your son.”

I could tell the man at the door was important by the way his brass buttons shone, and the way Father stood stiffly and Mother wrung her hands. They turned their backs, and I knew I wasn’t supposed to hear. But I crept closer, partly hidden in the kitchen. My sister, Olive, almost 10 years older than me, had been patching a shirt in the sitting room. As I peered around the corner, I saw she was on her feet behind Father and Mother, her mending discarded.

The brass button man stood with compassion in his face as he said those words: “You and your family can be very proud of your son…”

I watched him hand Father a telegram. I didn’t know why Mother began to weep.

“No,” Father said hoarsely, “we’re not.”

Olive straightened.

“Speak for yourself,” she said.

The man held his hat in his hands and offered his condolences. Confused by Father’s response, he was gracious and quietly took leave of them.

My young mind raced, trying to understand what I had witnessed. Father. Mother. Olive.

The man at the door . . . was bringing news of Nelson, our brother.

“But,” I whispered, unable to contain my questions.

Father turned to see me peering around the corner. That moment should have been private; his face, I’ll never forget.

Two years earlier, when Nelson enlisted, Olive told me he left for our sake. He would not charge his own sisters’ future to the lives and deaths of other men. Olive was a schoolteacher and a wonderful person; she must have been worthy of his sacrifice, I thought. She made Canada a better place because of the future he gave her. But I didn’t want to be someone worthy of sacrifice; I only wanted my brother back. Was I a bad, ungrateful sister?

I remember how he would play the French horn for us on winter evenings. I thought its sound as cheery as its gleaming exterior. But now I know it to play the melody of missing someone.

He used to sing in his strong tenor for me on days I came home from school feeling glum. He would spin me around until I was dizzy, bouncing with his voice, to make me laugh as the world tipped. I had looked forward to hearing that voice again when he returned.

The minister preached on pacifism for weeks after he left. Couldn’t he have volunteered with the other Mennonite boys? Because our people do not go to war, our family’s neighbours and cousins were sent away to build and mine and farm while soldiers fought and died. The other Mennonite boys came home, having been cold and hungry, but alive. Why did Nelson think he needed to die so I could live? I feared I must become something great so his death would not be in vain.

For months after Nelson left, I had overheard Father repeatedly telling Mother they must make a decision. Mother would keep her back to Father, busying herself with cooking or washing while he spoke; she was terribly quiet. Until one day when she wasn’t.

“No!” She turned on Father. “Nelson is our son. I’ll not shun him. He has not turned his back on us!”

“Everything that we believe…!” Father roared.

Mother ignored him. “He writes to us regularly.”

“He has nothing to say to us!” cried Father.

“He attends church when he can,” she continued. “He is his own man and must be allowed to make his own choices. I will not cut him off. When he returns home, I will welcome him. I expect you to do the same.”

Mother turned to leave the kitchen.

“Writing letters and attending church do not make up for his betrayal of our ways. Love thy neighbour. Thou shalt not murder.”

She turned back to face him. “And what would you do?” she said evenly. “Could you shun your own son? And what if he does not return from this god-forsaken war?”

Never had I felt so alone, listening from the sitting room. Olive was boarding near her teaching post and Nelson was away. Something within me, in my chest near the base of my throat, shattered. The idea that he might not come home overwhelmed me; breathing felt like a weight.

“Our people do not go to war. He has betrayed our family and our faith.”

“Is that all you see? A traitor, instead of a son?”

Our family had rarely been much for chatter, but since the news of Nelson’s death, the house had been tomb-silent. I did not know how to break the silence, to ask the questions that had been accumulating since that day.

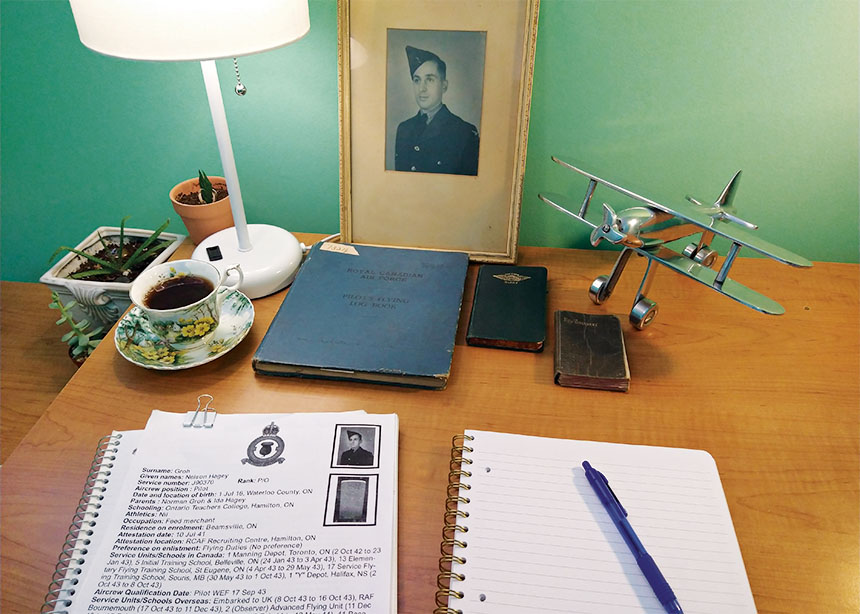

His personal effects arrived much later to a still silent house, addressed to Olive, not Mother or Father. A few photographs and medals, a flight logbook, his uniform, the letters Olive had sent him regularly, and a teddy bear. So little to be the sum of his life. Olive whispered to me that the bear had been his flying mascot, a gift from a ladies’ sewing circle near where he had been stationed, to welcome Canadian pilots. It had fur like a real animal, a warm brown colour, and beady eyes, but I dared not touch it.

Soon after, I found Olive searching the library, looking up what each of his medals meant, muttering to herself about our people’s self-imposed ignorance. But when she saw me, she shut the book.

She had not accepted his uniform, telling the solemn boy delivering it that surely it could be of more use to someone else.

“Those who live by the sword die by the sword.”

Mrs. Martin said so to Mother in the grocery store, standing by bags of flour, near where there should have been sugar.

I watched Mother. Her back became rigid; her hands clutched the grocery basket. She lifted her chin, almost imperceptibly.

“My son,” she said quietly, “was a good man,” and turned on her heel. I scuttled after.

But once we were home, I saw her hands shake, her shoulders droop. Our community was small; everyone knew when Nelson had enlisted, while their own sons were sent away to volunteer as Conscientious Objectors. And everyone knew when he was killed in action, piloting a machine of war, a sacrilege, a betrayal of our people; words I learned from neighbours’ whispers.

I sat on the back porch of our house, where I had spent summer evenings watching fireflies with Nelson and Olive, now wishing desperately to run, hide somewhere, but knowing that if I ruined my dress Father would not be forgiving. The small memorial was over. No one had mentioned his service nor cause of death, only reinforcing our shame.

I was afraid he would be forgotten; no one would speak his name, no one would see his face. His picture would stay hidden in Mother’s dresser, and his memory would disappear. Afraid that they wanted him forgotten. I cried alone, knowing I could never remember everything he was, and I could never be enough to be worthy of his death.

“Millie,” Olive said softly, sitting down next to me. “Perhaps you would like to keep his bear.”

She held it out in careful, steady hands.

I swallowed and took the bear gingerly, afraid somehow that if I dropped it, the memory of my brother would shatter.

“I’ll take good care of you,” I whispered.

I hid the bear in the wardrobe behind my Sunday dress. I sewed an Air Force blue hat and pinned it over his ear. Some days I whispered to him: stories of my day, thoughts, memories and reasons I missed my brother.

As I grew older, I argued with the bear; why it was wrong to go to war; why it was right. Other days, ashamed, I distinctly avoided his hiding place. But I remember the man at the door, hat in hands, telling us to be proud of my brother.

And while the minister damned him and neighbours shunned him, Olive and I held onto him silently. Though all of us, his family, still loved him, we never again spoke his name.

A.S. Compton lives in Waterloo, Ontario, and is part of the Canadian Mennonite team. This work of creative non-fiction is rooted in the life of her great uncle, Nelson Groh, and was written after many visits with her great-aunt, Mildred Nigh (Nelson’s youngest sister). Though creative liberties were taken, some of the dialogue and most of the general facts are from Nigh’s retelling and family lore.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.