At WBUR, Boston’s National Public Radio station, a very interesting testimony appeared three years ago titled “A Dual Degree from Oxford. A Medical Degree from Harvard. Neither Protected Me from Racism.” It’s from Tafadzwa Muguwe, a Zimbabwean-born Rhodes scholar and Harvard-trained physician.

Back in the U.S., an early memory from medical school was seeing a white patient after the professor left the room for a moment. “Where do you go to school?” the patient asked. My white coat was emblazoned with “Harvard Medical School” in large red letters above the front pocket. ‘Harvard,’ I responded.

“Howard sends students here?” The patient found it easier to imagine I was visiting from the preeminent [historically black university]—450 miles away—than belonging to the current institution, as embroidered on my white coat. Who, then, belongs at Harvard? . . .

Early in training, I received feedback from a professor who remarked, “Internationals like you do well on tests but struggle with clinical skills.” Ironically, I was receiving credit for testing well, but in the same breath, the goalposts were shifted. It wasn’t the last time I would hear from this professor, and ultimately, these encounters proved detrimental. I wondered, what do others with influence believe? How is the institution failing people like me? Over time, I’ve developed a sensitivity from the accumulation of these microaggressions.

My Flashback Memory 1: At my previous Mennonite home church in B.C., where we spent 15 years, my family was part of the balcony gang. We always sat there with a few other families and people of colour with a mere hope of designating this place as an international welcome arena. An old white man always sat two rows behind us; we sometimes exchanged greetings. He was a church greeter. One day when we entered the church with our two daughters, who grew up in this church, one of them went to retrieve a bulletin from the greeter. He responded by saying, “You no speak English?” Can you imagine how our daughters responded? They fumed.

My Flashback Memory 2: As an Asian male pastor and first-generation immigrant to Canada whose mother tongue is Korean, I often hear unsolicited feedback from anonymous white congregants: “Your English is good to hear!”

Little do they know that I have invested more than 40 hours to prepare and practice the sermon and to also print out an additional transcript. When I hear comments like this, it shuts down and shrinks my confidence in public speaking. The comment overlooks the content of my character and the material I just preached on. I question what their perception is of other ethnic people due to their English skills.

According to Kevin Nadal, a professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, microaggressions are “the everyday (usually brief and routine) verbal, nonverbal and environmental slights, snubs or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative message to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership” (such as a racial minority).

The reason why “micro” is attached to aggression is that people who express these insulting words or behaviours are not aware of them. Yet this level of micro does not mean it has a small impact. It is quite the opposite; it can bring life-changing harm. According to Nadal, someone commenting on how well an Asian American speaks English, which presumes the Asian American was not born here, is one example of a microaggression. It also makes the assumption that Americans must speak English fluently.

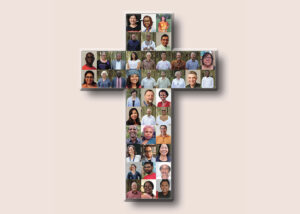

No one is immune to committing microaggressions. What the intercultural church sternly asks of us is how to raise and reinforce our level of cultural sensitivity in order to create a harm-free environment for the unity of the intercultural community.

The success of pursuing an intercultural church does not come from an audacious mission statement and great leadership but from a sensitive mindset in the pews and podium to cherish every detail of dealing with people—their feelings, emotions and psyches. This is a very delicate divine enterprise.

Two saints’ words are pertinent. Therese of Lisieux said, “It’s not the big things that make us saints; it’s the little things every day.” Teresa of Calcutta said, “Be faithful in small things because it is in them that your strength lies.”

Oh yes, small always matters!

Joon Park serves as intentional interim co-pastor at Holyrood Mennonite Church in Edmonton. He can be reached at cwcfounder@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.