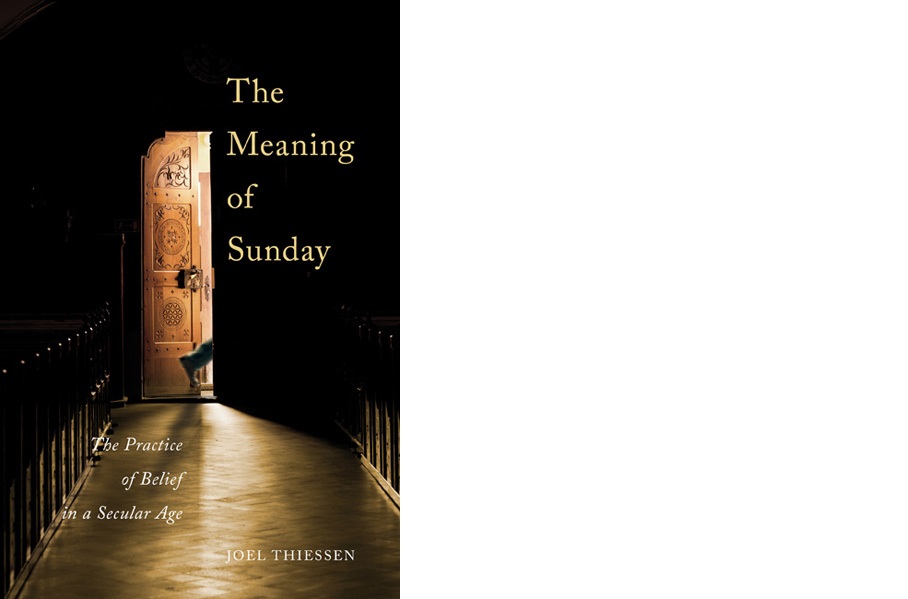

Following in the footsteps of Reginald Bibby, sociologist Joel Thiessen examines how Canadians of today view Christianity. In his book The Meaning of Sunday, he concludes that religion is increasingly being pushed to the margins of society and is regarded as less important as the years go by. Canadians tend to believe that religion should be restricted to the private realm because each person experiences it differently, and they believe religion tends to divide, rather than unite, society. Thiessen is not optimistic about the future of Christianity in Canada.

Between 2008 and 2013, Thiessen interviewed 90 people in and around Calgary. He interviewed 43 males and 47 females from a broad range of ages and from a variety of Christian denominations, both Roman Catholic and Protestant. There is no indication that any of his interviewees were Mennonite. His goal was to compare the religious experiences and beliefs of three groups—active affiliates, marginal affiliates and religious “nones.”

Among his findings are that active affiliates, like everyone else, are not keen on having beliefs imposed on them. There is growing diversity within denominations and congregations because members tend to hang on to their own beliefs, rather than accept the pronouncements of the pastor or the denomination. Thiessen also points out that studies show active affiliates give more to charity and volunteer more than other Canadians.

Thiessen found that marginal affiliates don’t think of religion in terms of costs and rewards, and tend not to believe that religion is necessary for morality. They turn to the church only because of tradition or to spend time with family. Thiessen calls them “free riders” because they value what the church provides but are not willing to invest time and energy into the church.

Using some of Bibby’s research, Thiessen points out the significant decline, since the 1970s, of Canadian adults and teens who attend church weekly. By 2008, only 37 percent of teens said they believe in God. Thiessen’s research shows that this trend is continuing and religious “nones” are the fastest growing group in Canada.

Thiessen argues that if religion is considered from a supply-and-demand perspective, there is too much supply and not enough demand. He says that of the top eight reasons that his interviewees gave for not attending church, only two of them related to what the church was or was not doing. Declining membership in churches is due to growing secularization and because society no longer considers religion important; he doubts there is much that churches can do to change the trend. In the interviews he found that people did not desire greater involvement.

“Where church attendance was once viewed in society as a non-negotiable priority . . . today Canadians are less inclined to bow to tradition or religious authorities to compel them to attend religious services regularly,” says Thiessen. Until the 1960s, religious leaders and religious organizations played an important role in society, especially in education, healthcare and social services. Today, that is no longer the case; in fact, society tries to restrict the influence of religion and there seems to be a sense that religion does more harm than good. No longer does it provide a common base for society.

While this is an academic book and Thiessen frequently refers to other scholarly research, I found The Meaning of Sunday quite readable. The anecdotes from his interviews are interesting, and the sentences loaded with names of other researchers can be quickly skimmed.

Although Thiessen’s conclusions are not optimistic about the future of the church in Canada, he maintains that this is reality. As Mennonite churches plan for the future, they should probably consider what Thiessen has to say.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.