The world’s most low-key Advent group

Categories: Feature ArticlesIn the middle of the pandemic darkness of the fall of 2020, when church gatherings were fraught, a small idea ignited. I sent an email to people I knew, inviting…

Sacred disruption

Categories: Feature ArticlesI don’t like the dark. If I can’t avoid walking into a dark room, I will use my phone’s glowing screen to break up the night until I reach the…

Five spiritual practices for waiting in darkness

Categories: Feature Articles1 Night sky meditation Go to a quiet spot, under the night sky. Pray with Psalm 8. (“When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon…

Waiting in the uterverse

On every one of my previous visits to the fertility clinic, the waiting room was full. Women of different ages, ethnicities and income brackets would take their seats in fertility…

If all the earth…

Nature has always been a source of inspiration for Mennonite children’s author, Aimee Reid. Several years ago, she took her dog for a walk while camping at Valens Lake Conservation…

MennoMedia evolves to meet challenges

Categories: Feature ArticlesJoan Daggett, project director of MennoMedia’s Shine: Living in God’s Light curriculum, tracks trends inChristian education as part of her work. We asked her about the challenges and opportunities for…

Whatever became of Sunday school

Categories: Feature ArticlesThey had forgotten about the kids. It was the 1980s; two major Mennonite denominations had merged, spending five years and a large sum of money to figure out how to…

Getting passionate about the bible

Categories: Feature ArticlesSunday school has been approached differently by different people. At times, the church has taken a defensive posture: It’s scary out there and we’re going to shelter you and teach you…

Finding a home in the MB conference

Categories: Feature ArticlesBrent Kipfer’s Mennonite Church Canada pedigree is solid: he grew up at Poole Mennonite Church in Poole, Ontario, attended Rockway Mennonite Collegiate, graduated from Canadian Mennonite Bible College and Anabaptist…

Switchers and exiters

Categories: Feature ArticlesWhy do people switch or exit a church or denomination? And why do some churches leave a denomination altogether? Chances are you could offer possible reasons from your own experiences or…

Leaving a church that left

Categories: Feature ArticlesHarv Wiebe—not his real name—did not agree with his congregation’s decision to leave the regional church, but still, he hoped things would work out for the congregation he had once…

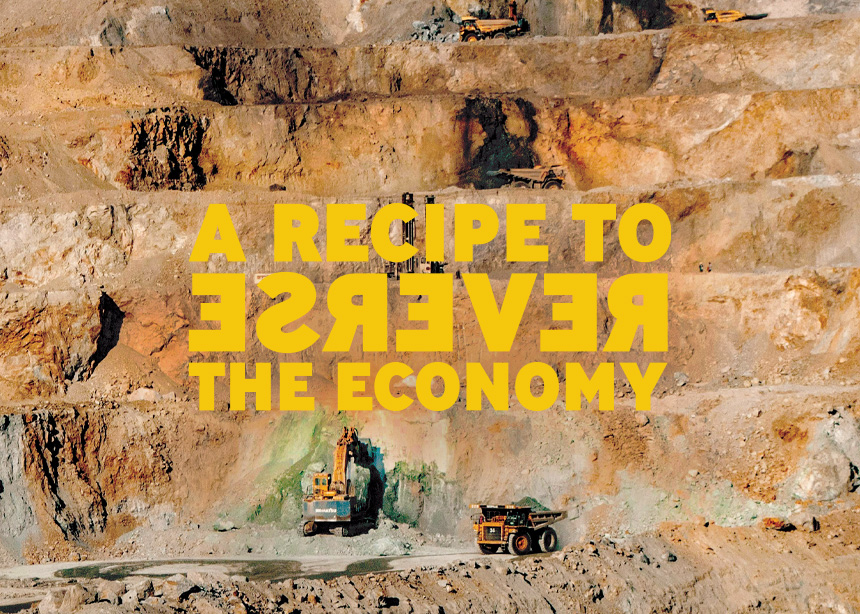

A recipe to reverse the economy

Categories: Feature ArticlesThe Mennonite more-with-less ethic is something I have always connected with. Shopping for clothes at the thrift store, commuting by bicycle and eating simple, tasty food are practices that have defined…

A slow, simple obedience

Categories: Feature ArticlesMy introduction to Anabaptism began with fire. Let me explain. I grew up in a Presbyterian household, but when I went off to the University of Toronto, a roommate introduced…

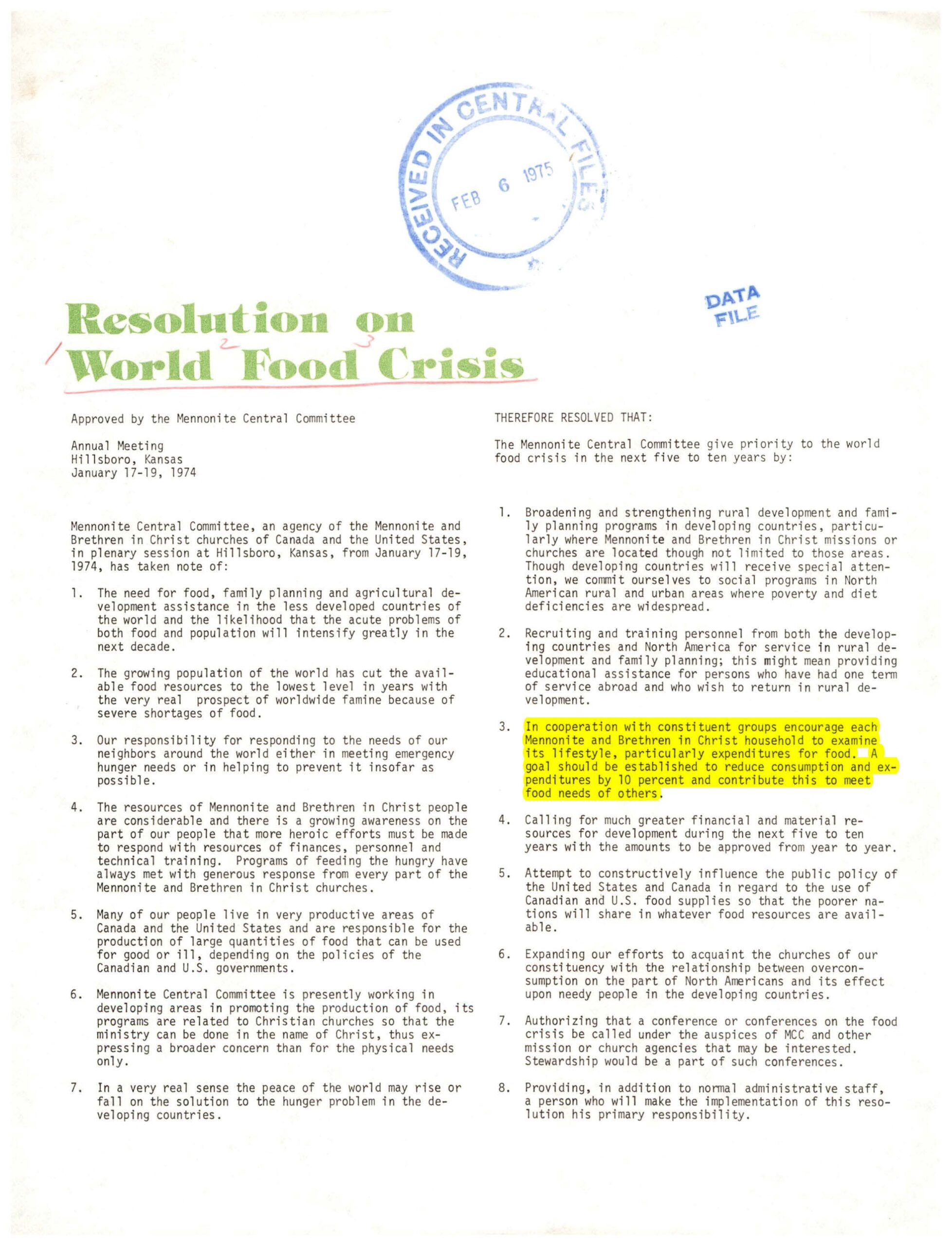

Hillsboro Resolution

Categories: Feature ArticlesIn 1974, Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) approved a resolution that encouraged each Mennonite household in North America to “examine its lifestyle” and adopt a goal to “reduce consumption and expenditures…

Actually, love your enemies

Categories: Feature ArticlesA couple of years ago my sister and I had hammock party at the park with our friends. The goal of a hammock party is to set up all your hammocks…

How to disagree with the beloved of God

Categories: Feature ArticlesIan Funk remembers the last time he arrived on campus at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS)—how he walked into the guest house late at night and was welcomed by a…

Reflections on Spiritual Transformation

Categories: Feature Articles“I think you are a contemplative.” Spoken by my spiritual director, those words caught me off guard. I’m not . . . am I? But the more I thought about it,…

Involuntary: Terminated MCC workers call for accountability and change

Categories: Feature Articles“I still use it,” Anicka Fast says of the brownish knitted potholder she received at Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) orientation in Akron, Pennsylvania, in 2009. Fast and her husband John…

Jeep Weekend

Categories: Feature ArticlesIf I’m not careful, I find myself surrounded by similar-minded individuals who are great at reflecting my own perspectives and values back at me. In a society that continues to…

Faith Before Flags

Categories: Feature ArticlesI spent my mid-twenties holding my disability flag high, confident that I’d found my calling. This was my cause. These were my people. Wholly devoted to the disability community and…