-

Three responses to the conundrum of conflict

Categories: Feature ArticlesWhen I tell people whom I’ve just met that my job includes working with congregations in conflict, typically they respond in one of two ways. Either, “Really? Churches have conflict?”…

-

Pain, apologies and repair following 2017 MC Canada restructuring

Categories: Feature ArticlesJeanette Hanson, director of International Witness for Mennonite Church Canada, began a Zoom call last spring with an apology to members of the Anabaptist Network in South Africa. “I told…

-

Two parents, two kids and an in-law

Categories: Feature ArticlesHalfway up the street in midtown Kitchener, Ontario, is a single, detached home much like the other houses around it, but inside, something unusual is happening. At least the neighbours…

-

Commitment to accommodate

Categories: Feature ArticlesThomas Bumbeh talks about cultural commitment to care for aging parents Living with extended family under the same roof has made sense to Thomas Bumbeh on several different levels throughout…

-

Tying Grandpa’s shoelaces

Categories: Feature ArticlesGrandpa’s shoelaces were round, not flat like my own. They were a challenge to tie up, even for my nimble fingers. He sat in his straight-backed chair at the kitchen…

-

Care comes around

Categories: Feature ArticlesIt’s been 20 years since Rebecca Harder, now 46, and her husband decided to permanently move into her family’s intergenerational home in Winnipeg’s western suburb of Charleswood. Harder’s grandparents, Mildred…

-

The world’s most low-key Advent group

Categories: Feature ArticlesIn the middle of the pandemic darkness of the fall of 2020, when church gatherings were fraught, a small idea ignited. I sent an email to people I knew, inviting…

-

Sacred disruption

Categories: Feature ArticlesI don’t like the dark. If I can’t avoid walking into a dark room, I will use my phone’s glowing screen to break up the night until I reach the…

-

Five spiritual practices for waiting in darkness

Categories: Feature Articles1 Night sky meditation Go to a quiet spot, under the night sky. Pray with Psalm 8. (“When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon…

-

Waiting in the uterverse

On every one of my previous visits to the fertility clinic, the waiting room was full. Women of different ages, ethnicities and income brackets would take their seats in fertility…

-

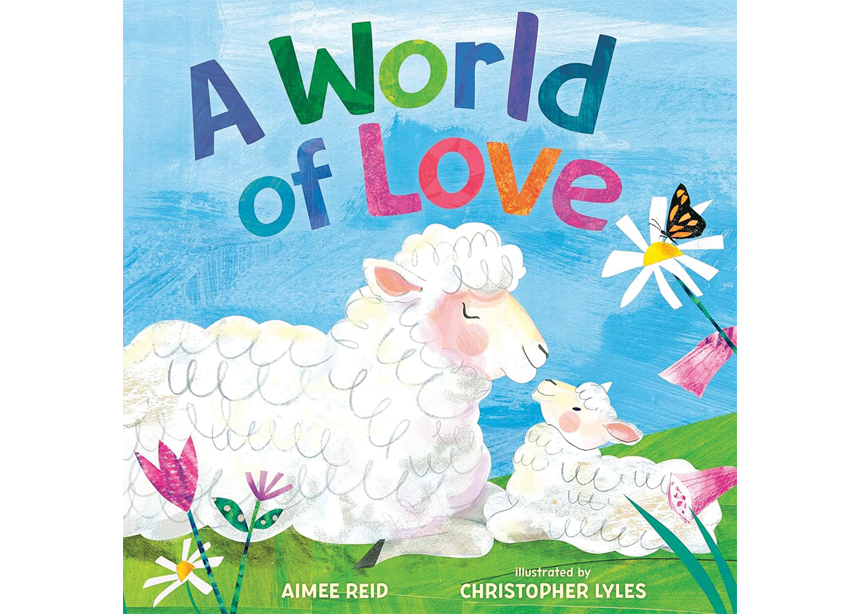

If all the earth…

Nature has always been a source of inspiration for Mennonite children’s author, Aimee Reid. Several years ago, she took her dog for a walk while camping at Valens Lake Conservation…

-

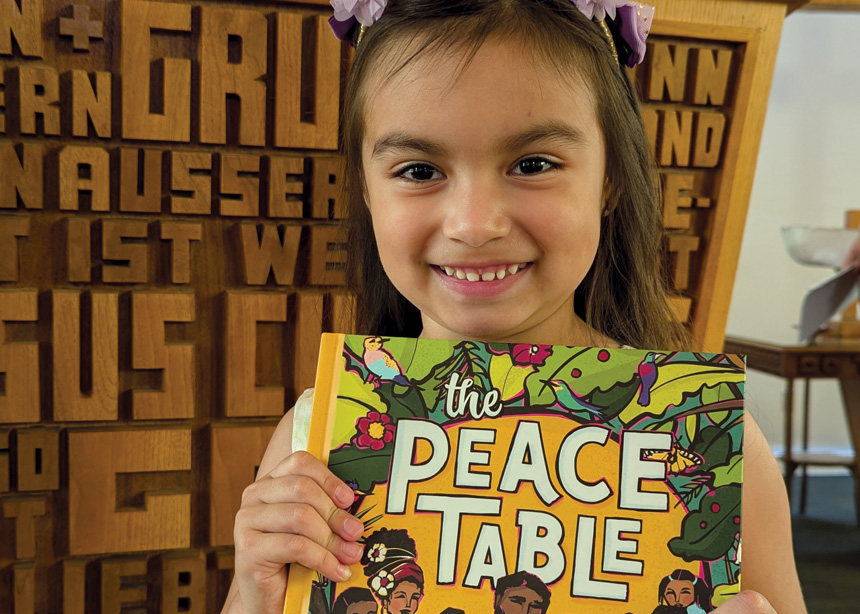

MennoMedia evolves to meet challenges

Categories: Feature ArticlesJoan Daggett, project director of MennoMedia’s Shine: Living in God’s Light curriculum, tracks trends inChristian education as part of her work. We asked her about the challenges and opportunities for…

-

Whatever became of Sunday school

Categories: Feature ArticlesThey had forgotten about the kids. It was the 1980s; two major Mennonite denominations had merged, spending five years and a large sum of money to figure out how to…

-

Getting passionate about the bible

Categories: Feature ArticlesSunday school has been approached differently by different people. At times, the church has taken a defensive posture: It’s scary out there and we’re going to shelter you and teach you…

-

Finding a home in the MB conference

Categories: Feature ArticlesBrent Kipfer’s Mennonite Church Canada pedigree is solid: he grew up at Poole Mennonite Church in Poole, Ontario, attended Rockway Mennonite Collegiate, graduated from Canadian Mennonite Bible College and Anabaptist…