Although I’m a pacifist who has never voted Conservative, I support the Conservative-led campaign to put a war hero’s face on the $5 bill.

All the more so after speaking about it with Don Plett, Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, who upset many in our denomination last year by blocking Bill C-262: An Act to ensure that the laws of Canada are in harmony with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

My reason for aligning with Conservatives on this is not just that I believe irony is good for the soul. It’s because the face they want on the bill is one familiar to me, in a way.

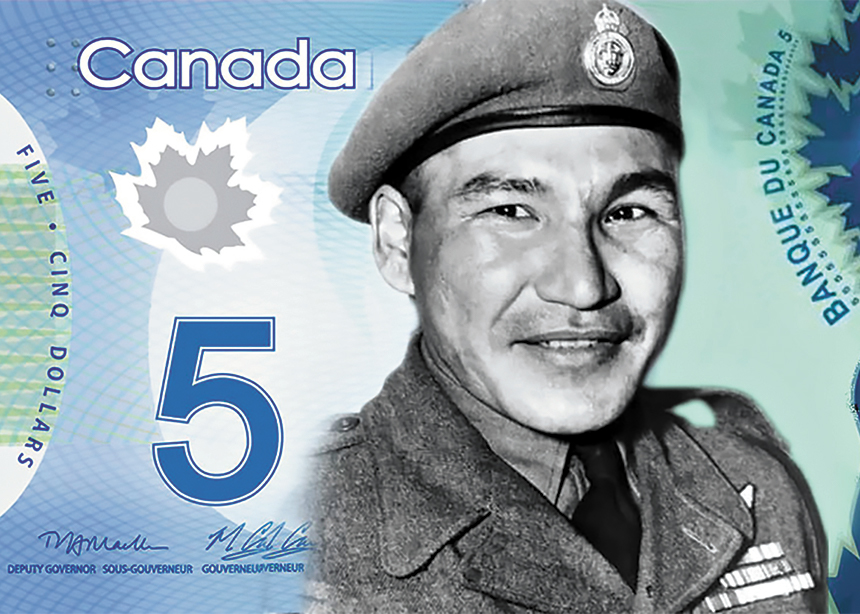

In 1968, my aunt and uncle adopted a six-year-old Anishinaabe girl named Karen, who had been in foster care for some years. Karen was born to Verna Sinclair and Tommy Prince of the Brokenhead Ojibway Nation in Manitoba. Tommy Prince, who served in the Second World War and the Korean War, is one of the most decorated Indigenous veterans in Canadian history with a total of 11 medals. A school in Manitoba and a street in Winnipeg are named for him.

It is Sergeant Tommy Prince, my cousin’s dad, that the group of Conservative MPs and senators, including Plett, want featured on a new $5 note.

Anti-racist money

The Conservative campaign includes a website (honourtommyprince.ca) with a video and petition. About 31,000 people have emailed the finance minister in support of Prince via the website.

The Conservatives acknowledge the racism Prince faced upon his return from war, when he and other Indigenous veterans were denied benefits received by other veterans. Prince eventually died homeless in 1977.

Prince is one of more than 600 people nominated to appear on the new bill. An advisory council will narrow down a short-list, based in part on public input, and the finance minister will make the final decision. The new bill will land in wallets in “a few years.”

Other notable nominees include Terry Fox, Nellie McClung, Tommy Douglas, Tim Horton and Lord Stanley.

Why Tommy Prince?

I favour Prince for three reasons.

First, for the sake of my cousin. I have not seen Karen in years, but family is family. If it is important to her, I’m in. “I feel very proud,” she tells me by phone from Calgary. “It’s such an honour,” she says of the nomination, which she learned about only after the campaign had launched.

How does she feel about the party behind the nomination? “I’m just glad that somebody has taken notice,” she says.

She acknowledges the stature of other nominees, saying, “I think they should put Terry Fox on the 10 or 20.”

My second reason for backing Prince is that, while symbols don’t replace tangible change, they do matter. I support prominent recognition of Indigenous people.

Broadening the tent

Thirdly, if the current period of heightened concern for racial reconciliation is to yield deep transformation and healing—not just victories over certain bad guys—liberals and conservatives need opportunities to work together.

That did not happen on Bill C-262. The private member’s bill—put forward by then-NDP MP Romeo Saganash—sought to bind government to the UNDRIP. Plett, who has been a Conservative senator for 11 years, led the effort to run out the clock on the bill before the last election.

Plett spent most of his life in Landmark, Man., and in the Evangelical Mennonite Church, although he now lives in Winnipeg and attends Calvary Temple. I spoke with him by phone for almost an hour.

Mennonite Church Canada had put much effort into pushing for Bill C-262, and encouraged Canadians to send emails to Senator Plett, urging him to back off. Plett was the bad guy. Many people did send emails, it turns out, not all of them overly gracious.

Given this history, and my intrigue with people who blur categories, my interest was piqued by Plett’s support for Prince. Then I found out, that on June 25, in the wake of the George Floyd murder, Plett rose in the Red Chamber to launch “an inquiry into racism and discrimination in Canadian institutions.”

Heartless Conservative?

I’m not naive about gross injustices perpetrated by Conservative governments federally and provincially. Nor those perpetrated by Liberal or NDP governments, past and present. No one is anywhere near perfect.

That said, I was very interested to read Plett’s speech on racism. Would it be political posturing?

At points he sounded quite unlike the supporters of Bill C-262. At other times, the opposite. He quoted comments on systemic racism by Liberal-appointed Senator Murray Sinclair, expressing gratitude to the same senator he clashed with over Bill C-262.

Plett said there is “much work to be done” because there are still people who are not treated as “equal members of this society simply because of the colour of their skin.” To conclude, Plett quoted Psalm 34, and said the obligation of senators is to “stand up for the brokenhearted and the crushed in spirit.”

I could critique Plett’s comments—he does not go as far as I would—but I am inclined to welcome them and learn from them. Not all paths to change will follow the same course, and no path is perfect. He can reach an audience that Saganash and Sinclair cannot, including many good people in our pews.

Lives matter

As for Prince on Canadian money, Plett told me: “It would signify the respect we have for our military men and women. . . and certainly right now, because of the big Black Lives Matter, Indigenous Lives Matter movement, I think it would be a great thing for the Indigenous community. I am proud to be part of that.”

When I asked how he would respond if he walked into a rural coffee shop and people critiqued the notion of Prince on the $5 bill, he questioned my implied assumption that such opposition would be common. Worth considering.

Perhaps I would encounter more opposition than he on such a matter, because I expect it and my perceived association to progressive attitudes might itself occasion resistance.

In terms of people who do express more critical views of Indigenous people, he says they see expenditures of money on reserves and “some of the negative results.” Plett values the opportunity he has had to see this from both sides. For many years, he operated a plumbing and heating company that did a lot of work on First Nations. “If you don’t see both sides,” he says, “you make a judgment on one side.”

Plett does not “adhere” to the notion of white privilege as a “fair” lens through which to view society or our forebears. But he does say, “We have not all been created with the same advantages.” Referring to realities he saw on First Nations, he says, “I have a better opportunity than someone born in a broken home or broken family.”

Plett versus MC Canada

If Plett wants fairness for Indigenous people, why didn’t he support Bill C-262? The bill would have benefitted Indigenous peoples by providing access to lands they traditionally occupied, or restitution where land cannot be returned. It would have required the “free, prior and informed consent” of Indigenous peoples before implementing laws affecting them and before approving projects affecting their lands.

Plett says the bill should have been costed by the Parliamentary Budget Officer, a step that is required of government bills but not private member’s bills. He said the bill would have cost trillions and there would not have been a project built in Canada without requiring Indigenous sign-off. He does not support that.

Some legal experts and Indigenous leaders have a more nuanced interpretation of free, prior and informed consent. Plett, and others, say the legislation should have defined it.

Senator Sinclair, who sits as in Independent, told CTV News at the time that the Conservatives knew free, prior and informed consent is “not a veto” and they were just saying that to create fear. “They know that the UN declaration does not create substantive rights in Canada,” he said.

Sinclair declined my request for a 15-minute interview about Prince and Bill C-262.

Plett suggests that Liberal support for Bill C-262 was not genuine. He asks why they did not push it harder in the Senate, and speculates they were not unhappy to see it die, especially with him taking the blame rather than them.

Liberals have promised to introduce their own 262-like bill.

Mennos in the trenches

I asked Plett how the pushback he received on Bill C-262 compared to other battles he has fought. He paused. Then he said it was “probably the toughest.” Part of the difference was the tone of some of the “attacks.” Other issues “never got that personal,” he said, singling out MC Canada members as the source of the bulk of the antagonism.

“People were preaching from the pulpit about what a bad person I was,” he told me, a mix of anger and sadness in his voice.

In public, Plett can come across as a hardened partisan scrapper, but none of us are one-dimensional. Amid that complexity, I was glad for the common ground created between us by Tommy Prince.

Diverse paths to change

MC Canada, and other church bodies, have focused much of their Indigenous-relations work on UNDRIP. That is important work supported by many prominent Indigenous people.

It feels almost sacrilegious to suggest we should collaborate with opponents of that approach or diversify the church approach.

Roger Epp, a professor of political science at the University of Alberta, sees great value in UNDRIP as something “really sensible” that can “help us think about a different way of living together.” He expresses concern, however, about the potential for it to be reduced to a litmus test or a matter of “a kind of admission into a certain sort of camp.”

I presume such a camp would exclude the Conservatives behind the Tommy Prince initiative.

Epp, who studies Indigenous relations in rural areas, draws at times on The Ordinary Virtues, a book by Michael Ignatieff, former leader of the Liberal Party. After ground-level research in eight countries over three years, Ignatieff concluded that the language of human rights, which was supposed to unite humanity under a common moral ethic, “remains an ‘elite discourse’, the lingua franca of an influential but thinly spread stratum . . . [of] people paid to think abstractly or campaign for a living.”

He does not say at all that the human rights movement—in which UNDRIP is rooted—is without merit. But I see in his findings an encouragement to engage people on a practical, everyday level, and to acknowledge the need for multiple entry points into discussions of injustice. Doing otherwise may shrink the audience, increase resistance and reduce common ground.

Who is my neighbour?

Epp builds on Ignatieff’s conclusion to ask whether the concept of neighbourliness can help us work toward better ways of living together. Neighbourliness is practical, localized and immediate.

The caution Epp offers is that neighbourliness cannot gloss over the sort of power and land dynamics addressed by UNDRIP and it cannot erase the fact that, for non-Indigenous people, “all of our ancestors have been beneficiaries of arrangements around land and political power.”

With respect to the Prince initiative, Epp says that honouring past heroes must not be a matter of closing a chapter of history and thus presuming to “achieve our innocence again.” Injustices experienced by Prince, persist.

Those caveats stated, though, Epp says, “Yeah, I’d carry that bill in my wallet.”

I presume Senator Sinclair would too, and Justin Trudeau. Common ground. A potential entry point for collaboration.

“I see using my dad’s legacy as an opportunity for education,” Karen tells me. I would like to think that education could span a truly broad spectrum of society.

Grace

I expect many of the 31,000 people who emailed the government in support of Prince—perhaps including the organizers—would not attend a workshop on UNDRIP. Both approaches, I would argue, can be steps in the right direction. And perhaps the most fruitful change happens when those two paths find common ground.

In his speech on racism, Plett asked, in relation to “cancel culture”: “How can we expect to educate one another and learn from each other when we pre-emptively remove individuals from the conversation? . . . As we take part in this important discussion, let’s give each other the benefit of the doubt. Let’s be gracious.”

I am happy to give the benefit of any doubt to Don Plett and the Conservatives behind the Tommy Prince initiative. It’s a perfect opportunity for collaboration of the imperfect.

And I hope someday to buy a cup of coffee for both Plett and my cousin Karen with a crisp new $5 bill that has a familiar face on it.

For discussion

1. Can you name the faces on Canadian money? How often do they change? What criteria would you use to determine who should be honoured in this way? Has a decrease in the use of cash made this honour less significant?

2. Will Braun writes, “I support prominent recognition of Indigenous people.” Why does Braun think it is important? Do you agree?

3. Has anyone you know been involved in encouraging the government to pass Bill C-262, an act that would ensure Canadian laws are in line with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples? What reasons does Senator Don Plett give for not supporting it? Are these valid reasons? What are some counter-arguments to this position?

4. According to Plett, he received personal pushback and antagonism from members of Mennonite Church Canada regarding the Bill C-262 debate. Are there issues that are so important that it is worth disrespecting an individual? What kinds of issues can lead us to lose our cool?

5. How has our society been harmed by acrimonious debate? What are some ways to be gracious in the midst of intense disagreements?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.