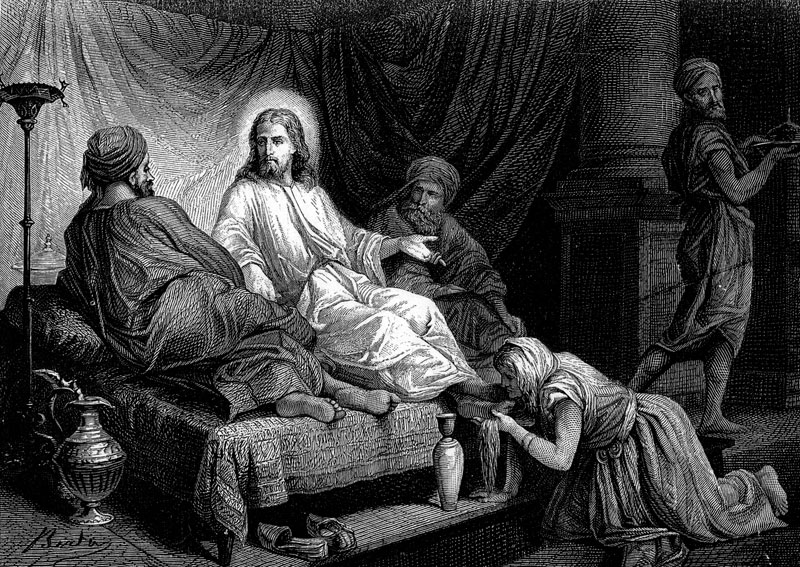

A woman—a good family friend—pours perfume worth $25,000 on Jesus’ feet at a dinner party held at her house in his honour. She removes her head scarf, shakes her hair loose, bends over, and wipes Jesus’ perfumed feet with her hair. The fragrance fills the whole house. Surely that fragrance remains on Jesus’ feet—and in Mary’s hair—for days.

The only place to start with this story is its sheer physicality. Jesus’ feet, perhaps beautiful, are more likely hardened and calloused from much walking. Mary’s hair, to be revealed only at home with family members, is now loosened, working its magic. The pure essence of nard, a healing oil, is reminiscent, it is said, of the lost Garden of Eden.

This is sensuous stuff, no doubt about it. I’m always astonished when biblical commentators ignore the obvious, moving immediately to theology or to symbolic meanings. What are they afraid of? I wonder.

Then, of course, there’s the stunning extravagance of Mary’s gesture: A vial of the most costly perfume available is worth a common labourer’s annual wage.

Are Mary of Bethany and her siblings rich? They seem to be Jesus’ regular hosts on his way to Jerusalem. Or is this rather the nest egg of a family of modest means? Is Mary pouring out the family nest egg on Jesus’ feet? If so, her brother Lazarus and her sister Martha utter no cries of protest.

The protest comes from Judas, the treasurer. Imagine what $25,000 could do for the House of Friendship, for Mary’s Place, for the work of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) or Mennonite Economic Development Associates (MEDA) and their partners in Haiti, for folks in refugee camps!

It’s almost as if this story deliberately offends, if not by its sensuous extravagance, then surely by Jesus’ commendation of Mary’s action. Most Mennonites would side with Judas on this one!

I suspect this story offends us from another angle also. It’s Mary’s piety. Her devotion to Jesus, expressed in such an unrestrained pouring out of herself. It’s way over the top; embarrassing, to say the least.

And yet I love this story. I love the way it shimmers in so many directions, like a diamond catching the sun. It harkens back to the story of the raising of Lazarus in the 11th chapter of John’s Gospel. It anticipates Jesus’ own washing of his disciples’ feet. It prepares us for Jesus’ death and burial, now inevitable. Beyond all that, Mary’s action attracts and challenges me, with my sober restraint about many things in life.

No bounds to gratitude

First, let’s look at how this text resonates in the Gospel of John. If asked the question, “What would you spend the family nest egg on?” many would likely say on healthcare for a loved one, perhaps on a promising cancer drug not covered by healthcare, or perhaps a new treatment for autism or Alzheimer’s.

In this story, though, a beloved family member, presumed dead and gone forever, dines at table with Jesus. What does the family nest egg matter now? Mary’s gratitude knows no bounds.

But Jesus reframes what’s going on here, taking Mary’s action beyond the realm of gratitude for past mercies. He makes of it also an act of love and care for himself, in anticipation of a future event coming all too soon. Mary’s gesture points to the way Jesus will pour himself out completely through his death. “She’s anointing me for my burial,” he says. “I’m not going to be around much longer.”

In the Gospel of John, it is the raising of Lazarus that seals Jesus’ fate. It functions in the gospel as a sign of Jesus’ own impending death and resurrection, and indeed the authorities are now plotting more seriously than ever to kill him.

People speculate, “Will Jesus even come to Jerusalem for the Passover feast this year? Surely it’s too dangerous.”

But here he is at his usual bed and breakfast five kilometres outside of Jerusalem, dining with his friends Lazarus, Martha and Mary before entering the city for the last time.

Of course, acts of love and care abound whenever a loved one is dying, and often they literally involve the special care of feet or the use of fragrant oils, whether during a weekend at a spa, at home or in palliative care elsewhere.

It is in this setting that Mary honours Jesus by anointing him openly, elaborately, while he’s still alive. We’re meant to notice the contrast with the secret disciples Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimethea after Jesus’ death. As discreetly as possible, they arrange for Jesus’ burial, bringing generous quantities of myrrh and aloes, oils often used together for anointing a body before burial. In contrast to Mary, they stay in the shadows.

Based in love, not duty

The story of Mary’s outpouring of love also moves us towards Jesus washing his own disciples’ feet at the Last Supper. Mary does for Jesus what Jesus will do for his disciples—and what he invites disciples to do for each other. Footwashing by Mary and by Jesus anticipates discipleship and service based not in duty, but in love.

Footwashing is an odd gesture in our world today, disconnected as it is from first-century practice, where a good host did provide water for travellers’ dusty feet, and where washing a guest’s feet was considered slave work.

I grew up with the ritual of footwashing, and as a teenager found it downright embarrassing. When I joined Rockway as a youngish adult, I was secretly glad to be rid of that antiquated ritual forever, or so I thought.

But then in the 1980s I spent a year at Conrad Grebel College as interim chaplain, while John Rempel was on a sabbatical. Rempel practised footwashing at Grebel, so I felt I needed to do so also. And to my surprise, footwashing took on life for me again. Students unfamiliar with this practice were overwhelmed by how it symbolized mutual caring between friends in a close commu-nity. I’m convinced that the very oddness of the gesture—and its sheer physicality—was part of the attraction for these young adults.

In the Mennonite Ministers’ Manual, Rempel writes, “Rituals condense vast realities into simple gestures. . . . In a setting of warmth and serenity, footwashing can be a gesture of love which words stammer to express.”

Gestures of devotion

We at Rockway still do not practise footwashing. But I wonder, what vast realities of love and care do we condense into simple gestures here? I’m thinking not of gestures that are elaborate or over the top. We generally don’t do those here. I think of people who share with us gifts grounded in the senses, moving us into beauty as we worship God. I think of gestures that give expression to church community, gifts usually of time rather than money.

What if we saw such gestures as creating the aroma of a caring, worshipping community? What if we saw them as ways of showing devotion, as ways of loving God and neighbour?

Or what if focused, intense creation care is an act of gratitude to God? What if love of theology is an act of devotion to God? What if justice and care for the most vulnerable in our community and our world is not primarily a duty, or even a mandate, but rather an act of gratitude and devotion to God?

What if those of us with a spirituality not quite the norm at Rockway swallowed our fear of being written off and offered to preach a sermon or lead a Sunday school class as part of our devotion to God? What if the rest of us received such offerings as a gift? What if more of us succumbed more regularly to spontaneous financial generosity in gratitude and devotion to God?

A spontaneous act

Occasionally I still ponder an incident from 20 years ago.

One evening I went with a girlfriend to a John Michael Talbot concert in St. Catharines, Ont. I sat there enjoying his contemplative Scripture songs while looking forward to stopping at a coffee shop on the way home to continue catching up with Mary (a pseudonym) at a time when her young children were not competing for my attention. I enjoyed Mary precisely because she was sponta-neous and creative, balancing me in good ways. Her family scraped along financially, which didn’t seem to concern her all that much.

Partway through the concert, I was surprised to find that the event was actually a fundraiser for a charity I had never heard of, apparently doing good things for the poor somewhere in the world. When the offering plate was passed, I put in a few coins. To my surprise, Mary slowed up the offering plate as she emptied out her wallet completely—putting in all the cash she had with her—$50 or so, I guessed.

Oh my, I thought. I wonder if that was grocery money! I actually asked her why she gave money to a charity she knew nothing about. If you’re going to do such a thing, I wondered why she didn’t give it to MCC.

Mary described it as a spontaneous act of love for God—and an act of trust that God would provide for her family. Suddenly the aroma of the other Mary’s perfume filled the air. But I continued to disapprove. My disapproval increased when Mary refused to let me pay for a cup of tea for her at the coffee shop, and we drove straight home.

I still don’t know what to make of my friend Mary’s action, or of my reaction, for that matter. I do know that I like the aroma whenever she’s in the room. And on the rare occasions when I succumb to spontaneous generosity—when I make a bit of a fool of myself in naming or expressing my devotion to God—I quietly thank my friend Mary and Mary of Bethany as well.

Sue Steiner is the past chair of Mennonite Church Canada’s Christian Formation Council.

For discussion

1. Sue Steiner tells the story of her friend who emptied her wallet in the offering plate at a concert as a spontaneous act of love for God. How would you have responded in that situation? Do you admire this person for her gesture, which she described as an act of trust in God?

2. Have you ever performed a spontaneous act of love for someone else? Do you agree that Mennonites are more apt to respond with “sober restraint” than spontaneous generosity? Why might that be? What are the advantages and/or disadvantages of being restrained?

3. What feelings does the symbol of foot-washing evoke in you? Do you agree that it can symbolize “mutual caring between friends in a close community”? What other actions can express “love which words stammer to express”?

4. How do you respond to Steiner’s suggestion that doing the work of the church is a gesture of gratitude and devotion to God? When is financial generosity an act of devotion to God? Are generous people spontaneously generous or have they cultivated the habit of generosity?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.