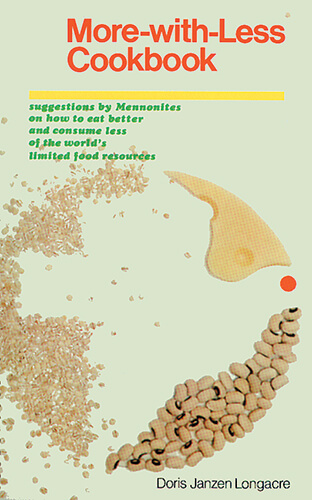

When I was a small child, my parents took our family on assignment to Chile as church workers. In a country which at that time had no Anabaptist-Mennonite churches, our ties to the Mennonite community took other forms. Among these, my parents’ use of Doris Janzen Longacre’s More-with-Less Cookbook was perhaps the most tangible.

So, although I didn’t understand it then, as our family ate our Whole Wheat Buttermilk Pancakes, Curried Lentils and West African Groundnut Stew, we were in a sense in fellowship across the distance with our Mennonite faith-family as well.

Fast forward to my university days, living in an apartment on the campus of a Mennonite university, and my roommate’s announcement that she wanted to eat vegetarian that year. Was that going to work with us sharing food costs? I agreed somewhat reluctantly, and we began leafing through my copy of More-with-Less that my parents had given me when I first moved away from home.

We read about how North Americans overeat protein and pored over the protein food charts. We learned that the vegetarian combinations of dairy with a grain, or legumes/beans with a grain, each make a full protein, and how the book’s cover—the cross-and-dove symbol of Mennonite Central Committee made out of grains of wheat, Swiss cheese and black-eyed-peas—is a clever reminder of these combinations.

Something about this uncompromising commitment to simplicity resonated deeply with our Mennonite sensibilities. I think we relished the challenge, but at that time we certainly didn’t make more than a cursory connection between our efforts to live simply, affordably and sustainably, as encouraged by More-with-Less, and the giants of Mennonite biblical and theological scholarship like Harold S. Bender and John Howard Yoder, whom we were reading for our courses.

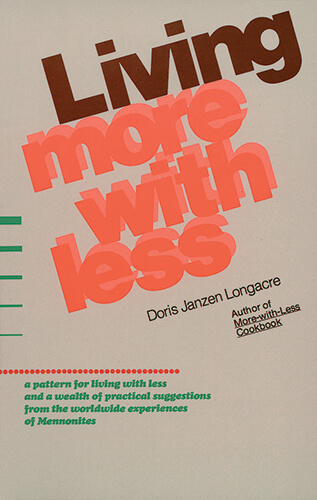

Since then, I have been living with, and into, Longacre’s more-with-less vision—both the cookbook and her later guide to simple living, Living More with Less—as I got married and my spouse and I set up our household together; as we had our first child; and as I’ve continued studying Mennonite and feminist theologies.

But perhaps surprisingly, it’s only recently that I have begun to understand it as a theology, albeit one which defies most conventions. Melanie Springer Mock introduced me to this intriguing notion in her essay, “Mothering, more with less,” in Mothering Mennonite, in which she makes the case that the More-with-Less Cookbook is “a foundational book reflecting late 20th-century faith and praxis. Much more than a book full of recipes . . . More-with-Less reflects Mennonite tradition, theology and change.” The change she speaks about encompasses both shifts within the self-understanding of Mennonite women in relation to the traditionally female roles of motherhood and homemaking, but also an increasingly global awareness, engagement and outlook among traditionally insular, “quiet-in-the-land” Mennonites.

Malinda E. Berry, a theologian and Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary professor, pushes this notion even further. For her, Longacre’s books do not simply “reflect” Mennonite theology, but themselves constitute a theology, which Berry, in her Ph.D. dissertation, “ ‘This mark of a standing human figure poised to embrace’: A constructive theology of social responsibility, nonviolence and nonconformity,” calls simply “more-with-less theology.”

She defines theology as “our talk about God,” concluding that more-with-less theology is comprised of “the connections we make between God’s unified presence in the universe and our response to God as we live within the world. More-with-less theology gives special attention to the ways that economic patterns and systems help or hurt this response to God and all that is around us.” She admits that calling the everyday, seemingly mundane choices surrounding the running of a household—or “homemaking”—theologizing may be a “leap” for some, but really, it makes sense to think of Longacre’s vision this way, particularly the five “life standards” she presents in Living More with Less. “In other words, [Longacre’s standards of] doing justice, learning from the world community, nurturing people, cherishing the natural order and nonconforming freely are part of our ‘household code’ as Christians. In this age of globalization, when our world is both a vibrant village marketplace and a groaning ecosystem, such a household code is more necessary than ever.”

Speaking to our experiences of “dwell[ing] with and in God,” Berry states in her essay, “The five life standards: Theology and household code,” in the 30th-annniversary edition of Living More with Less, that “God gives us homes, and how we make them matters.”

The implications of understanding Longacre’s more-with-less vision as Mennonite theology struck me as profound. First of all, as a woman studying theology, I was excited to discover another female Mennonite theologian hiding in plain sight, so to speak, and one whose thought has been so influential!

If we follow Berry in calling Longacre a theologian, then we also recognize her underlying insight that more-with-less homemaking is a way of putting one’s faith into practice; despite its seeming ordinariness, it’s a form of discipleship and witness. In her dissertation, Berry recounts the stories of people whose lives were transformed by the “gospel” or “good news of simplicity and nonconformity as preached and interpreted by Longacre,” which has also led some to the Anabaptist-Mennonite faith and church.

With this assertion comes a deeper recognition: that more-with-less theology affirms the sacredness of what has traditionally been women’s work and wisdom as integral to discipleship. This is indeed a radical affirmation! In writing her cookbook, Longacre joined a genre “initiated and produced by women,” which had a formative influence on “Mennonite cultural understandings, . . . historical development and sociological identity,” according to Marlene Epp, a professor of history and peace and conflict studies at Conrad Grebel University College, in Mennonite Women in Canada: A History.

In her essay, Mock presumes a common disdain for cookbooks as “the provenance of domesticity” and “mere guides to the kitchen,” but argues that More-with-Less, in particular, helped—and even prompted—women to navigate the changing gender roles of the 1970s. It could be called an embodiment of the feminist slogan, “the personal is political.”

Unlike mainline forms of feminism which undervalue domesticity and motherhood as irredeemably tainted by the “feminine mystique” (the sexism of women being limited to the kitchen alone), Longacre’s revisionist, gender-egalitarian vision both upheld the value of what has traditionally been women’s work, tracing its importance within the life of faith, and thereby made it relevant to both women and men. To declare Longacre a theologian illuminates this feminist thread running through her work as well.

Even Longacre’s method is unconventional and so, arguably, makes a theological statement. In gathering together the collective wisdom of Mennonites, including suggestions that North American Mennonites have learned from living within “the world community” on other continents, Longacre does several things:

- She uses “crowdsourcing’” long before the Internet age and thus creates a communal document.

- She affirms practical experience and the wisdom gleaned from that experience, as well as various cultures and perspectives outside of North American capitalist-consumerism, including the voices of the poor and marginalized, which help us North Americans subvert the wasteful and exploitive excess of our culture.

In “Poised to embrace,” Berry calls this Longacre’s “organic” or “homegrown” theologizing, and draws parallels to African-American womanist theology.

Remarkably, despite being a homemaking “expert,” in that Longacre taught university-level home economics, she didn’t use her expertise to correct others or draw attention to her own superior knowledge. Instead, she affirmed others’ more-with-less insights in all their simple, practical glory. It’s telling that, in 1979, when the 39-year-old Longacre tragically died from cancer without yet completing Living More with Less, her community stepped in to finish her important work; it was truly a collective effort.

These days, as I harvest my garden boxes and preserve what food I can for my family for the coming winter, I’m thinking of Longacre: of her encouragement to live simply; and of the theological merit of how we share our meals, raise our children, and make our homes.

She was a theologian who “nonconformed freely” to that very term, a woman of faith who practised the justice and intentionality she preached, a teacher and mother whose message has reverberated within and beyond the Mennonite faith-family and across the decades, as evidenced by the 30th-anniversary edition of Living More with Less. What a legacy to leave behind after such a short life!

I invite you to remember Longacre, the theologian, in your everyday efforts to live simply and faithfully, keeping in mind the core of her more-with-less theology, which Berry has so aptly summarized: “God gives us homes, and how we make them matters.”

Susie Guenther Loewen is a regular blogger for Canadian Mennonite. She attends Charleswood Mennonite Church in Winnipeg.

See also “More-with-Less: Changing the world, one recipe at a time”

For discussion

1. Which pages in your recipe books are splattered because you use them frequently? Which are the cookbooks most dear to your heart? Does More-with-Less have a place in your collection? Has the more-with-less concept influenced Mennonites you know?

2. How much do you think about simplicity, affordability or sustainability when you choose what to cook or eat? What do your food choices say about your values? Do you consider yourself a more-with-less homemaker?

3. Susie Guenther Loewen quotes Malinda Berry, who writes that “doing justice, learning from the world community, nurturing people, cherishing the natural order and nonconforming freely” are standards taught by Doris Janzen Longacre in the More-with-Less Cookbook and Living More With Less. Do you agree? Are these the standards that you aspire to when you make choices in your kitchen?

4. How have women’s roles been changing since More-with-Less was first published in the 1970s? Is cooking still considered predominantly a female responsibility? Do we value the task of food preparation less than earlier generations did? Should we value it more than we do?

—By Barb Draper

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.